1749 NEW ENGLAND / BOSTON PURITAN RELIGION BOOK That Forever Changed Puritanism!

Lot 84

Estimate:

$1,000 - $1,500

Absentee vs Live bid

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $10 |

| $200 | $20 |

| $300 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $200 |

| $3,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,000 |

| $30,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 | $20,000 |

| $300,000 | $25,000 |

| $500,000 | $50,000 |

About Auction

By Early American History Auctions

Jun 1, 2019

Set Reminder

2019-06-01 12:00:00

2019-06-01 12:00:00

America/New_York

Bidsquare

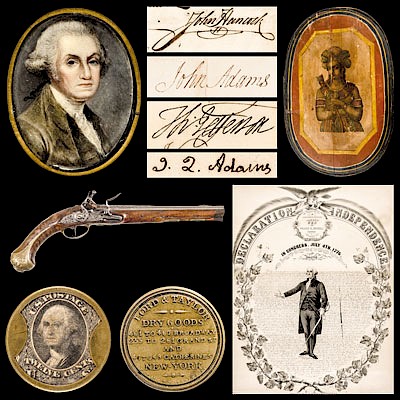

Bidsquare : Historic Autographs, Colonial Currency, Political Americana & Revolutionary War Era

https://www.bidsquare.com/auctions/early-american-history-auctions/historic-autographs-colonial-currency-political-americana-revolutionary-war-era-4152

Historic Autographs, Coins, Currency, Political, Americana, Historic Weaponry and Guns, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

Historic Autographs, Coins, Currency, Political, Americana, Historic Weaponry and Guns, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Early American History Auctions auctions@earlyamerican.com

- Lot Description

Colonial America

1749 NEW ENGLAND / BOSTON PURITAN RELIGION Only Two Copies Located on WorldCat

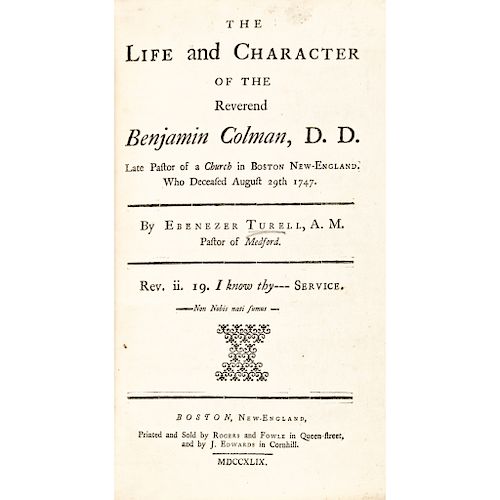

1749-Dated Colonial America, Boston Printed Hardcover Book titled, "THE LIFE AND CHARACTER OF THE REVEREND BENJAMIN COLMAN, D.D.; LATE PASTOR OF A CHURCH IN BOSTON NEW-ENGLAND. WHO DECEASED AUGUST 29TH 1747.", Very Fine

Rare original Colonial Boston Printed Religious treatise written by Ebenezer Turell (1702-1778), printed by Rogers, Fowle and J. Edwards, at Boston. Author was a Harvard graduate, noted Patriot and longtime Minister in Medford, Massachusetts. Benjamin Colman (1673-1747) was noted Puritan nonconformist who did much to forever alter the course of Puritanism in America. Puritan Minister Benjamin Coleman was the author whose tract on "The Government and Improvement of Mirth" demolished for perceptive posterity the cliche of New England Puritans as a "humorless" lot. This very rare and historic book remains in nice condition. It has been rebacked, bound in contemporary calf leather, with a red spine label. There is light to moderate cover wear from use, the hinges neatly reinforced with cloth tape, lacking the half-title page which is replaced with a corner piece excised from front blank. Overall, expected scattered foxing, and generally clean internally. This historic volume collates: [14 (of 16)], i, [3], 238, [2] pages; and it measures about 8" tall x 5.5" wide x 1" thick. WorldCat locates only two institutionally held copies in book form; One at Harvard, and the second in the Memorial University of Newfoundland Library Collection. Evans 6434.

"After much searching and fasting, a new minister, Ebenezer Turell, was hired (by the Church) in 1724. He served for 54 years, during which time he baptized 1037 people, married 220 couples and admitted 323 communicants to the Church. A new meetinghouse was built during Rev. Turell's ministry at 227 High Street. Completed in 1727, it was twice the size of the previous Church with a large steeple rising from its center. In an effort at frugality, it was decided that each man should build his own pew, at his own cost." [Source: The Unitarian Universalist Church of Medford, Massachusetts].

"Benjamin Coleman was the Puritan Minister whose tract on 'The Government and Improvement of Mirth' demolished for perceptive posterity the cliche of New England Puritans as a humorless lot. Yet Minister Colman's career, beginning at the turn of the 18th century, reflects significant, if subtle, changes in New England Puritanism, and in literary taste as well." (Meserole, Harrison T.; American Poetry of the Seventeenth Century. Pennsylvania State University, 1985).

"By 1698 tensions within the religious community in and around Boston had reached the breaking point. A group of modernists, inspired by the latitudinarian spirit of England, plotted a change... Around the young conspirators coalesced a larger group, most of them men of business... Their plan was to form a new church that would reflect their own modern views, and where they could escape from the stultifying control of the older generation... The ring leaders invited a college friend, Benjamin Colman, to come from England to take on the job of minister... Benjamin Colman was exquisite. Many people noted it... when he stepped ashore at Boston, he brought a new elegance of language into the old Puritan city." (Hall, Michael Garibaldi. The Last American Puritan: The Life of Increase Mather. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988).

The Puritans were a significant group of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England. The designation "Puritan" is often incorrectly used, notably based on the assumption that hedonism and puritanism are antonyms: historically, the word was used to characterize the Protestant group as extremists similar to the Cathari of France, and according to Thomas Fuller in his "Church History" dated back to 1564. Archbishop Matthew Parker of that time used it and "precisian" with the sense of stickler. T. D. Bozeman therefore uses instead the term precisianist in regard to the historical groups of England and New England.

They were blocked from changing the system from within, but their views were taken by the emigration of congregations to the Netherlands and later New England, and by evangelical clergy to Ireland and later into Wales, and were spread into lay society by preaching and parts of the educational system, particularly certain colleges of the University of Cambridge. Initially, Puritans were mainly concerned with religious matters, rather than politics or social matters. They took on distinctive views on clerical dress and in opposition to the episcopal system, particularly after the 1619 conclusions of the Synod of Dort were resisted by the English bishops. They largely adopted Sabbatarian views in the 17th century, and were influenced by millennialism.

In alliance with the growing commercial world, the parliamentary opposition to the royal prerogative, and in the late 1630s with the Scottish Presbyterians with whom they had much in common, the Puritans became a major political force in England and came to power as a result of the First English Civil War (1642-1646). After the English Restoration of 1660 and the 1662 Uniformity Act, almost all Puritan clergy left the Church of England, some becoming nonconformist ministers, and the nature of the movement in England changed radically, though it retained its character for much longer in New England.

Puritans by definition felt that the English Reformation had not gone far enough, and that the Church of England was tolerant of practices which they associated with the Catholic Church. They formed into and identified with various religious groups advocating greater "purity" of worship and doctrine, as well as personal and group piety. Puritans adopted a Reformed theology and in that sense were Calvinists [as many of their earlier opponents were, too], but also took note of radical views critical of Zwingli in Zurich and Calvin in Geneva. In church polity, some advocated for separation from all other Christians, in favor of autonomous gathered churches. These separatist and independent strands of Puritanism became prominent in the 1640s, when the supporters of a presbyterian polity in the Westminster Assembly were unable to forge a new English national church.

"Benjamin Colman irritated conservatives when he returned [to America] in 1699 from a four-year sojourn in England to be the pastor of the new Brattle Street Church, which announced that it would admit members without a narrative of conversion. Traditionalists felt aggrieved, and it did not help that the congregation defined the duties of the pastor and his flock by appealing to 'the dictates of the law of nature' or that Colman introduced to provincial Boston 'a grand and polite' rhetorical style modeled after the prose of Joseph Addison in England. But Colman's theology illustrated the caution that marked the new spirit." [Holifield, E. Brooks. Theology in America: Christian Thought From the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War. Yale University Press, 2003].

"Led by Thomas Brattle, the Urbane Treasurer of Harvard College...a group of Boston's well-to-do merchants undertook in 1699 to build a meeting house where they could worship in style. 'Every baptized adult person', they declared, 'who contributes to the maintenance', was to have a voice in choosing the pastor of this new church, and public professions of faith were no longer to be required...These intentions amounted to much more than a frittering away of time-honored convention. To some historians, the Mathers have seemed extravagantly defensive in accusing these 'innovators' of plotting 'utterly to blow up all'. In the final analysis, however, they were right: the 'Manifesto' (1699) of the new church, and more explicitly a pamphlet entitled 'The Gospel Order Revived' (1700), both written mainly by Benjamin Colman, amounted to flat declarations that the basic Puritan concept of the gathered church was obsolete." [Heimert and Delbanco. The Puritans in America: A Narrative Anthology. Harvard University Press, 1985].

"By 1698 tensions within the religious community in and around Boston had reached the breaking point. A group of modernists, inspired by the latitudinarian spirit of England, plotted a change...Around the young conspirators coalesced a larger group, most of them men of business...Their plan was to form a new church that would reflect their own modern views, and where they could escape from the stultifying control of the older generation...The ring leaders invited a college friend, Benjamin Colman, to come from England to take on the job of minister...Benjamin Colman was exquisite. Many people noted it...when he stepped ashore at Boston, he brought a new elegance of language into the old Puritan city." [Hall, Michael Garibaldi. The Last American Puritan: The Life of Increase Mather. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988].

The Puritans were a significant group of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England. The designation "Puritan" is often incorrectly used, notably based on the assumption that hedonism and puritanism are antonyms: historically, the word was used to characterize the Protestant group as extremists similar to the Cathari of France, and according to Thomas Fuller in his "Church History" dated back to 1564. Archbishop Matthew Parker of that time used it and "precisian" with the sense of stickler. T. D. Bozeman therefore uses instead the term precisianist in regard to the historical groups of England and New England.

- Shipping Info

-

Early American provides in-house worldwide shipping. Please contact us directly if you have questions about your specific shipping requirements.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB