World War II Letter & Photo Archive of Capt. Charles H. Foertmeyer, M.D., 305th Medical Battalion, 80th Infantry Division

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 19, 2020

Cowan’s Auctions, a Hindman Company, is pleased to present the November 19 Fall Auction, featuring over 400 lots of historically significant photography, manuscript material, artwork, and other ephemera dating from the 18th through the early 20th century, including the Civil War. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

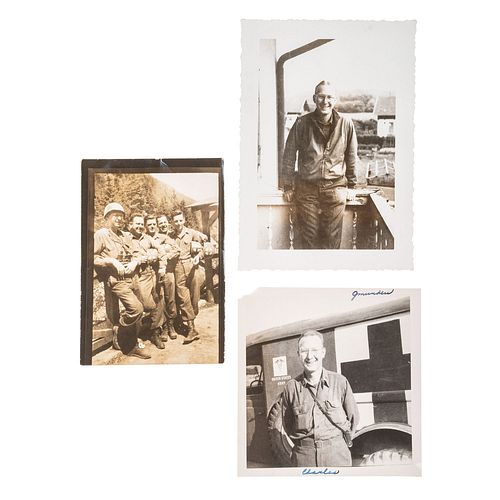

Outstanding World War II archive consisting of more than 500 letters (some V-mail) spanning July 1943-December 1945, nearly 500 photographs, and a hand-drawn pencil portrait attributed to French artist Robert Salvagnac, all documenting the service of Captain Charles Henry Foertmeyer., M.D., an American field surgeon who served with the 305th Medical Battalion, 80th Infantry Division, Patton's 3rd Army. Foertmeyer was awarded the Bronze Star and served as the medical head of the German POW camp at Biessenhofen, Germany. Letters are addressed to his wife Virginia Louise Driskell Foertmeyer with some written on confiscated enemy letterhead such as from "Consolato d'Italia," a Hauptschule in Schwanenstadt, and the office of a Nazi Gauleiter. Accompanied by 7 CDs with digitized files of the photographs in the collection, many of which were taken in the summer of 1945 at Biessenhofen and at Bad Worishofen, Germany, the site of a displaced persons camp in the American occupation zone. Born and raised in Cincinnati, OH, Dr. Charles Foertmeyer (1917-2011) attended the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. He married "Ginny" Driskell on August 7, 1943 at Carlisle Barracks in Carlisle, PA, just a few weeks after his July 16, 1943 enlistment. Foertmeyer landed on Utah Beach in France in mid-August 1944, and witnessed "hard fighting" as Patton's army raced across Europe in pursuit of German forces. His responsibilities included caring for the American troops and setting up hospitals to provide examinations of German prisoners. At Biessenhofen he was responsible for discharging German soldiers, many from the 6th German Army, for return to civilian life in Germany. Foertmeyer's letters to his wife reveal a thoughtful, educated, and dedicated soldier. Limited by censors (with redacting evident in some correspondence), the battle content is minimal. Still, Foertmeyer's observations on warfare and the Germans are insightful and powerful. Similarly, his personal photographs, nearly all of which are labeled, provide a remarkable visual insight into his experiences most notably during the post-war occupation. Photographs document fellow soldiers, landscapes, villages, war-damage, Ebensee concentration camp, displaced people, and German POWS. Together, Foertmeyer's letters and photographs represent a wonderfully thorough record of a WWII doctor's experience.New to combat, Foertmeyer's early letters reflect the ravages of warfare that he was now experiencing firsthand. On Sept 1, 1944, he writes from France: "The French surely are glad to see the Americans. When we pass thru the liberated towns, they pack the sidewalks 10 deep. They wave, throw flowers and carry on hysterically. / There is a small town about a block from our camp, which was just liberated this morning. Parts of it are burning yet. The Germans locked the men and women in the houses and set fire to them. They took the young girls into the fields and raped them. This morning the towns folk are shaving the heads of a few of the women who associated with the Germans." Then on Sept 9, 1944, he offered this assessment: "...early this morning I was in a town where the S.S. troopers had killed every civilian and destroyed every building...I have finally come to the conclusion that the German race should be exterminated - or atleast the nation (as a country) be abolished...I am not getting hard or cruel, but one can only witness the results of such fanaticism and cruelty for so long and then the thoughts of trying to re-educate and reconstruct these personalities, who have produced these crimes, is abolished."Foertmeyer also was keenly aware of the previously inconceivable peculiarities of practicing medicine in a warzone. He offered this thought on Sept 22, 1944: "Honey, you should see some of the ritzy contraptions I have rigged up for giving blood and plasma. I have become quite a shock expert. They call me the 'Plasma Kid' now. / This is a peculiar world here. For instance yesterday: The artillery shells were flying overhead, men were dying in the tents, the doctors working furiously, a red cross truck was dishing out doughnuts and coffee, and a loud speaker was blasintg forth swing music. its a weird picture - like one of these modernistic surealistic [sic] pictures." During the months of December and January as the Battle of the Bulge waged, Foertmeyer was also aware that the tide was turning, writing on Dec 24, 1944: "I do believe the war will now be shorter than anticipated. The show down battle has come, I believe."On April 1, 1945, Foertmeyer was in a German POW camp which he described to Ginny in this way: "I was in a German prisoner of war camp, just liberated, in which there were many America, British, Russians, and french. Some had been there for 5 years. You can bet this was a happy easter for them. I wish I could be permitted to tell you the stories I heard, the sights I saw, and the reactions to the liberation I observed..." This letter is also noteworthy because it is one of nine letters written on the letterhead of "Der Gauleiter / Des Gaues Hessen-Nassau / Der NSDAP." The Gauleiter who was head of the Hessen-Nassau Gau was Jakob Sprenger, who along with his wife committed suicide on May 7, 1945.Letters in the summer of 1945 show more leisure time, and often include details about the circumstances and locations in which his photographs were taken. He also remarks often on his displeasure with the lack of morality displayed by others, particularly officers, in his battalion. The sketch accompanying the lot is mentioned in a letter of September 19, 1945. "An artist wandered into our station station looking for work. I put him to work and now I have a large pencil portrait of you." The artist, who signed his pencil drawing "Robert Salvagnac 19-9-1945" was not just another portrait artist. Robert Salvanac, who at one point had been offered a position with Disney animation, was a French artist conscripted by Goebbels to do animated Nazi propaganda films. Sketch measures approx. 9.5 x 11.75 in.Foertmeyer served in France, Luxembourg, Austria, and Germany with a division that was in near constant combat. With letters written nearly every day from November 1944 through November 1945, this archive is an exceptional record of Dr. Charles Foertmeyer's service and the service of the 305th Medical Battalion, 80th Infantry Division. All items descended directly through the family.Letters in good condition and easily legible. Sketch with very small dots of soil. Most photographs in good condition given age.

Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB