War Date CSA Letter Archive of Tennessee Senator Joseph Brown Heiskell

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 21, 2019

On June 21, Cowan’s Auctions will be offering a remarkable selection of historic photography, letters, documents, flags, political ephemera, and more representing the Revolutionary War-period through the Civil War, Indian Wars, and beyond, as well as the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

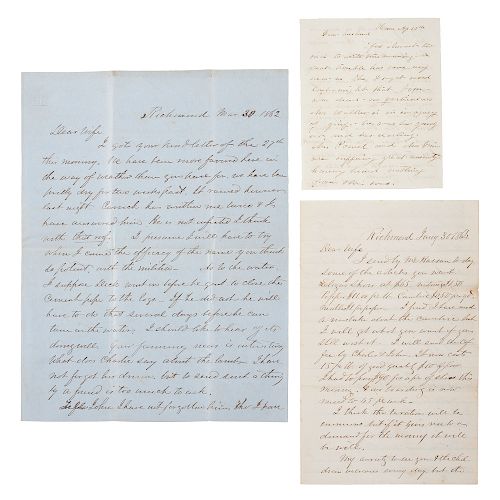

Lot of 28 letters. Epistolary archive of Joseph Brown Heiskell (1823-1913) with correspondence primarily between Heiskell and his first wife, Sarah, spanning nearly the duration of the Civil War.

Born in Knox County, Tennessee, Heiskell attended the University of East Tennessee (now the University of Tennessee), studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1844. With Sarah, he had seven children, five of whom lived to see adulthood. Heiskell served on the Tennessee State Senate as a member of the Whig party from 1857 until 1859. A proponent of secession, he was elected to both Confederate Houses following the outbreak of the Civil War. Heiskell served on the Judiciary and War Tax Committees, championing the cause of Confederate industrialization and advocating for southern civilians trapped behind enemy lines. In 1864, his was captured by Union soldiers and imprisoned until the end of the war. Following his release, Heiskell moved to Memphis and practiced law. He was elected Tennessee attorney general (1870-1878) and also worked as a reporter of the state Supreme Court.

Most of Heiskell's letters were written in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy. He frequently discusses politics, including pending legislation and personnel appointments. In a letter from October of 1862, Heiskell shares details of a Senate committee bill designed to organize Confederate troops into regiments and battalions. Additionally, he writes that he now chairs “a committee named to examine and report upon the armory and ordnance workshops ” and he hopes “to make it useful to the government by increasing the production of arms .” Naturally, Heiskell devotes considerable content to the war, describing an encounter with the controversial General James Longstreet (“a Sphinx. . . [we] can make nothing out of him, where he is going, what he will do ”) and relaying battlefield updates (“There is no doubt that [General] Hoke in North Carolina has captured 2500 prisoners, 30 guns, and 100,000 pounds of bacon ”). In two separate letters from the spring of 1864, he discusses the massacre of African American troops at Fort Pillow and the fate of Confederate General Nathan Forrest: “Lincoln is making very ridiculous threats about retaliating for Forrest’s Fort Pillow affair. . . it is the first time the law [against arming slaves] has been carried out and I intend to make it the subject of a special vote of thanks. . . [if Forrest is in fact dead] it would be almost as great as the loss of Genl. [Stonewall] Jackson. . . the Plymouth affair [capture of Union-held Plymouth, NC] is a very brilliant one and Fort Pillow a most Glorious affair. ” Heiskell does not shield his wife from the realities of war or the intricacies of political policy. In fact, he even solicits her advice on a bill that would reduce soldiers’ pay (“I am not surprised to see your views on the Compensation bill.” ).

Sarah’s letters to her husband are similarly detailed and provide lyrical commentary on political and wartime events. On February 25, 1862, shortly after the first meeting of the Confederate congress, she shares her excitement with her Heiskell: “ I feel that Congress occupies just the same position that the revolutionary congress did just before the declaration of independence .” Following a devastating raid in March of 1862, Sarah asks her husband if the government can “ buy the cotton and burn it. . . so that the blood hounds of plunder may have nothing to run after. ” The next week, she writes that while reports of recent victories in Missouri are confirmed, “the loss of our Generals – among them the brave McCullough – half dashes the cup of joy from our lips .” She frequently mentions a neighboring family, the Netherlands, whom she suspects of disloyalty to the Confederate cause (“ the Southern feeling at Mrs. N-s is only skin deep ”). Sarah also makes reference to her brother-in-law Carrick W. Heiskell (1836-1923), a lieutenant in the 19th Tennessee infantry, who would eventually be promoted to the rank of colonel and suffer injuries during the Battle of Chickamauga.

One additional letter written to Heiskell by Lieutenant Colonel James W. Rogan on February 15, 1862 contains an update on the ongoing assault on Fort Donelson, located near the Tennessee-Kentucky border: “Another fight at Donelson yesterday, in which the gun boats were seriously damaged. It is expected that a general fearful battle will be fought there today .” Also with an account from Nashville concerning a Union spy: “There was a suspected spy arrested here day before yesterday. He was formerly the sheriff of Shelby Co. & is now said to be a captain in the Lincoln army. ”Letters are in generally good condition, with toning and creasing as expected, given age.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB