Union General, Edward Wild, Civil War Archive

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 21, 2014 - Nov 22, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

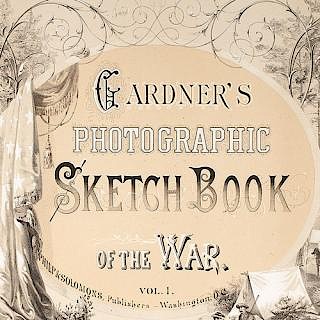

Union General, Edward Wild, Civil War Archive

18 letters, 3 CDVs, and 2 associated items.

An archive of letters concerning Brigadier General Edward Augustus Wild. Eschewing his medical training, he enlisted on May 22, 1861, as a captain in the 1st Massachusetts Infantry, commanding two companies of the regiment at First Manassas. He was wounded at Fair Oaks in the Peninsular Campaign. Promoted colonel to command the 35th Massachusetts Infantry, he was severely wounded a second time at the battle of South Mountain, when a musket ball shattered his upper left arm, requiring amputation at the shoulder.

After recovering, he was promoted to brigadier general, and tasked with organizing the freed slaves of North Carolina into Union infantry regiments. He led what became known as "Wild's African Brigade" on operations in the Carolinas and the siege of Petersburg, ending with occupation duty in the former Confederate capital of Richmond. Immediately after the war, Wild worked in asserting military control in Georgia, including helping establish Freedman's Bureau offices.

Most of these letters were sent to Wild's mother, and consist not only of letters from Wild himself, but many from his wife and brothers. The archive starts out strong with a letter dated August 4, 1861, from Fort Albany in Alexandria, VA. In it, Wild gives a vivid description of how the different sounds of the various deadly projectiles hurtling towards him seemed like being trapped inside a gigantic pipe organ. Relating how his two companies were left hanging on the left flank after the collapse of the Union Army, he describes how they ended up in Alexandria and were pressed into service preparing for a possible Confederate attack.

A September 29, 1862, letter from Wild's wife Ellen to his mother describes his trek to seek medical aid after his arm was shattered in battle, passing houses full of wounded, and climbing fences in the dark while holding his bad arm with his good one. When stretcher bearers found him, the first ambulance they came to had General Reno's body in it, so they continued on.

Wild, an ardent abolitionist, was proud of his black brigade. In a postscript to a September 17, 1863, letter from Folly Island SC, he notes, Wagner and Gregg have fallen. Some of my men were of the foremost to rush into them. They being all night in the trenches, armed themselves with pikes from the ditch of Wagner, and rushed upon Gregg, ahead of everything.

In 1864, Ellen came to live at Brigade HQ, and on September 19, she writes a charming letter to her mother in law describing the primitive conditions in camp. In July 1865, Wild warns Ellen: This will be no place for you for a long time yet. The Rebels are beaten, but not subdued…. the people are beaten, they submit, some decently, but the majority in a surly & grumbling manner, and too many of them vent their spite on the poor Negroes. Slavery is in full force in all the rural districts outside the reach of the military arm, & within our reach there are constant outrages, mainly by the planters, but some by the Negroes.

Many letters regard the health of Wild's father, who had apparently suffered a stroke. Several others are written by Ellen to Wild's mother, so that Wild would not have to write twice with his single arm. Also included are two full-length CDVs of Wild, taken in Boston, and one bust portrait taken in Union-controlled Norfolk, which shows a scar on Wild’s left eye after being wounded.Research documents about the life of Edward Wild are also includedCondition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB