The Pioneering Hockaday Family of Missouri and Kentucky, Archive Incl. Correspondence, Photographs, and Land Grants Signed by

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 9, 2017 - Jun 10, 2017

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

200+ items, mostly correspondence, as well as some family photographs, ca 1812-1883, from the pioneering Hockaday family as well as the Mills family, both from Missouri and Kentucky.

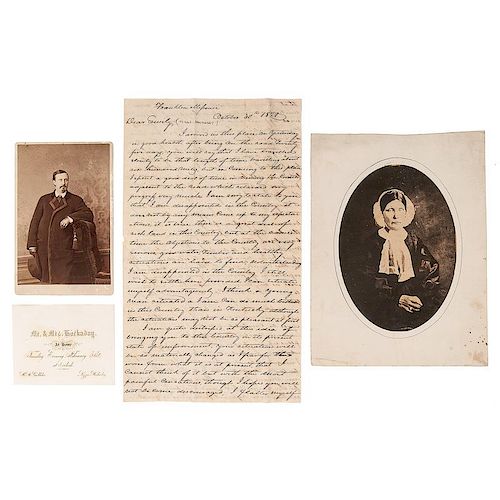

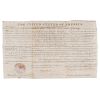

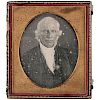

Includes: 77 letters, ca 1822-1870, from John and Lucy Mills of Winchester, KY to their daughter Emily Hockaday or other members of the Hockaday family, including Irvine O. Hockaday; 37 letters to Irvine from friends and family, 1812-1863; 4 letters, 1812-1818, concerning the Boone family and Missouri; 27 legal documents, mostly lists of taxable property, that includes the numbers and ages of Hockaday’s slaves; December 18, 1824 issue of the Missouri Intelligencer No. 6 Vol. VI 4 pp. with article speaking about the Convention of St. Petersburg concerning compensating slaves from slave holding states Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia, as well as a second article about the Treaty of Ghent and compensation for property taken including slaves; February 21, 1829 page from The Jeffersonian with at least two cases presided over by I.O. Hockaday; 1827 manuscript land survey for a tract surveyed by Benjamin George; a broadside of The Expunged Resolution of the US Senate on March 28, 1834 published in Washington March 28, 1864; Andrew Jackson presidential signed land grant for area in Missouri signed on March 1, 1831; three John Quincy Adams signed land grants for land in Missouri, dated May 1, 1826 and January 1, 1828 (2); sixth plate early daguerreotype portrait of who appears to be an elderly John Mills, although this cannot be confirmed, and printed photographs of Mills and his daughter Emily Mills Hockaday.

The Hockadays were long-time residents of Kentucky and settled there early in its history. They knew the Boone family, and Irvine Hockaday was friendly enough with Alphonso Boone, Daniel Boone’s grandson, to share a few letters; one of which is included in the lot. Consistent with the pioneering spirit of Daniel Boone, Alphonso and his father set out for Missouri as early as 1818 to survey territory. They expect to be gone all winter, Irvine’s aunt, Margret, wrote to him (Ohio, October 18, 1818). Less than two years later, Irvine followed his friend west to Missouri. Before he departed for the frontier, he proposed to Emily Mills, the daughter of Dr. John and Lucy Mills of Winchester, KY. From the plains, Irvine wrote his sweetheart about territory and his prospects:

I arrived in this place on yesterday in good health, after being on the road twenty five days, you will say that I have traveled slowly to be that length of time traveling about 600 miles, but in coming to this place I spent a good deal of time in viewing the country adjacent to the road which retarded my progress very much. I am sorry to say that I am disappointed in the country it does not by any means come to my expectations, it is true there is a great deal of rich land in this country, but at the same time the objections to the country are very serious, good water, timber, and healthy situations are hard to find; notwithstanding I am disappointed in the country I still wish to settle here provided I situate myself advantageously. I think a young man situated as I am can do much better in this country than in Kentucky although the situation may not be so pleasant at first. I am quite distressed at the idea of bringing you to this country in its present state of improvement, your situation will be so materially changed as I prefer the worse from what it is at present, that I cannot think of it but with the most painful censations, though I hope you will not become discouraged, I flatter myself that it will terminate our mutual advantage and happiness. I am well apprised and convinced that young men situated as I am cannot prosper and do well without undergoing many privations and conveniences in the early part of life and I do consider myself one of the happiest men when I recollect that one like yourself has consented to become the partner of my cares and perplexities of this life…I am now making to establish myself in this country is with the entire view and expectation of promoting your happiness as well as my own (Irvine, Franklin, MO, October 30, 1820).

A few weeks later, he wrote a similar letter to his future father-in-law, but added that the legislature of this state was still in progress and made several new counties, but had not found their courts or appointed judges. He doubted that he would receive a position as judge because he had several powerful opponents who were citizens of Missouri, which he felt was a great advantage (St. Louis, November 17, 1820). Nevertheless, he received his appointment as a circuit court judge and as treasurer of Calloway County, laying the foundation for the fabulous wealth he and his family later enjoyed. He became one of the most prominent citizens in Missouri and helped found the city of Fulton. After Emily moved to the frontier, her mother wrote her, I must confess I have never experienced such trials before I think nothing can equal I with me to be separated from any part of my family I think if ever we should all meet again I shall know what happiness is and not until then (Lucy Mills, Winchester, September 20, 1822). They would be separated for a considerable amount of time. Irvine’s work and their nine children kept them from traveling to Kentucky, although some of their children lived with their grandparents later.

As Missouri changed, so did Kentucky. John, Emily's father, was particularly affected during the Second Great Awakening in the United States and wrote to his daughter about the sea of new believers traveling to many revivals in their town. He described to his daughter:

On Friday February 1 as preparatory of the administration of the Lord’s Supper, meeting was held as usual on such occasions, after or during the service enquirers was called on to take seats near the pulpit, there were scarce but some few approached; on the day following this plan was renewed, and more, perhaps double their number came forward; this was again the case on Sunday evening and an immense crowd came forward; meeting was held again on Monday, and the numbers have been continually adding and meetings held twice a day ever since, and it has just broke up or rather adjourned until Tuesday, to give place to all to attend a Methodist meeting to be held from this evening until Monday, and on Tuesday the Presbyterians commence again. And o my dear child could you witness the affecting scene of your poor old mother assisting some ten or fifteen others going from person to person administering the consoling promises of the savior along the benches to the enquirers for you are to understand that their number have now become too great for the minister to converse with[illegible] all; these with him takes up two hours at each meeting; and there to hear the sweet effeminate voices of the Boys that are now converts praying in publick and the most solemn silence observed by all it would melt the stoutest heart; no rains or storms prevent the meetings; stores and taverns are shut up while whole households press up…what I would give if you could only be here… The Methodists held their meeting four days instead of two and about forty or fifty have joined them during the meeting about half of them blacks and amoungst them Matilda and (Billy) a boy I have swapped off Henry for…It has been several months since I have been awakened, but the revival has quickened me afresh, and such an outpouring of the spirit was never been seen in my days (September 10, 1835).

Matilda, Billy, and Henry were all slaves owned by John at one time. He was a moderately successful farmer, but a more successful doctor. Like many agrarian Southern gentlemen, he owned slaves, but very few. Census records indicate that in 1820 he owned seven slaves. Thirty years later, that number was reduced to five. Therefore, it is interesting that during revivals slaves and other African Americans were invited to attend church meetings with their owners and worshiped in the same space.

John also mentions a rapid series of arsons supposedly committed by a group of five African American men found hiding under the steps of one of the buildings. After making a full confession, a judge sentenced them to hang a few weeks later (September 10, 1835). After the hanging of a 16-year-old boy, he describes that possibly 10,000 people attended the event. He mentions other cases and legal happenings in the area he thought would interest his son-in-law, Irvine.

Similar to Emily’s family, Irvine shared a close bond with his children and his in-laws. All the Hockadays exchanged letters and wrote often to, Elizabeth “Lizzy” Hockaday, while she helped care for her cousins at her grandparents’ home. Health, as always, was a major topic of the letters. An epidemic of cholera unsettled the family in 1849. Issac McGirk wrote to his sister-in-law, Lizzy, We are all afraid of the cholera and father will not let us eat even a green apple, it goes so hard with me that I am compelled to steal them (Fulton, MO, August 3, 1849). Teasing Lizzy and highlighting his love of sweets he continued, Mag and Ev won’t bread and molasses without crying for it. You must not get married before you come home, so that I can get plenty of cake (Fulton, MO, August 3, 1849). Lizzy, however, would never be a bride. Almost all her sisters, on the other hand, found suitable matches.

As often is the case of a large family, there was a favorite. Lucy, the family favorite, was well loved and had a vibrant personality. She attracted the attention of prominent Kentucky livestock herder, Solomon Van Meter. Their union was very brief. Within a year of their marriage and soon after the birth of their only daughter, Lucy died. She was only 26. After hearing of her death, Irvine responded mournfully:

Your grandfather’s letter of the 26th giving us the truly melancholy tidings of the death of our dear Lucy came to hand a few days ago, this news was a great shock to us you may be sure, we can hardly realize the fact, we are so reluctant to give her up, she was dear to us indeed, we had our hearts so much let upon her, and we were in every respect so proud, and perhaps vain of her, that we almost feel that it has been a visitation of providence sent to teach us that we were giving too much of our affections to one of this world and not bestowing love and reverence enough to our heavenly father, but after all the ways of providence are mysterious and past finding out…I feel very much for you, I know you feel lonely and miss your sister more than we do, and in addition you have the care and trouble of her dear little babe, this I hope will be of no great trouble to you, but rather a pleasure to have charge of the dearest object of her affections save one…take care for it until it can be sent to your mother…I believe that possession of the baby is the only thing that will quiet her grief…We are anxious to know the state of mind you sister Lucy died in, how did she meet death? Did she meet it calmly and quietly and with a hope of future happiness? I long to hear what she did—I know she was naturally of very timidness(?) and weak nerves, and fear that the idea of death alarmed her greatly, but hope that the Lord gave her in her time of need, strength and fortitude to meet her destiny with composure and resignation…if it was otherwise I do not want to hear it…(Fulton, MO, December 12, 1849).

The family received Lucy’s youngest daughter, renamed Lucy, after being orphaned at ten. She remained in Kentucky until her grandparents relocated with her to Missouri in 1860.

Although the Hockadays were slave holders (as indicated in the taxable property lists in the archive dating from 1836-1856, which notes their slaves) they did not support the Confederacy, like the majority of their extended family. Emily wrote to her daughter Margret and husband Isaac M. McGirk about how distressed their grandparents were when they heard their troublesome relation, Willie, joined the Confederate Army. I earnestly hope it is not true [that he joined the Confederacy], wrote Emily, If it is the poor boy is utterly lost and sacrificed (Fulton, MO, February 24, 1862). Emily and Irvine's son, John and son-in-laws’ R.B. Price, Issac McGirk, and James Stephens joined the Union. We are much gratified at [them taking the oath] and relieved that they have returned to their allegiance, wrote Emily (Fulton, MO, February 24, 1862). Even though they supported the Union, Emily mentions that their negros behave remarkably well, better than most everybodys, implying that they might have owned slaves in Missouri (Fulton, MO, February 24, 1862). More trouble came when William McGirk was imprisoned for suspicion of treason. The family wrote a group letter to their daughter, Margret McGirk, assuring her of his innocence and offering their sympathy. Lord grant(?) he can prove himself clear of any disloyal act and be permitted to remain at home, wrote Emily. As soon as your Father learns what is done in the premises he will do all he can to relieve him if it can be done we fear it cannot be done when there is so many arrested that they will carry out [illegible] tyrannical plans (November 3, 1862/63).

Irvine died suddenly in 1864. Emily continued on without him, living at their farm with her children until her death in 1890.

Range in condition, most letters are in good condition but many, especially the early letters, have some holes in the paper that inhibits the legibility as well as damp stains, toning of the paper, and some brittleness. The land grants are in good condition, some with their original but faded seals.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB