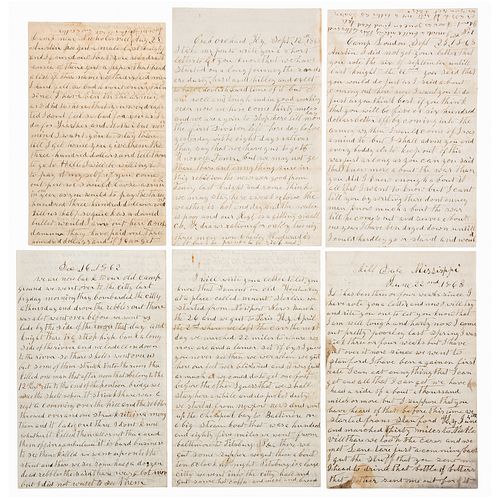

Six Civil War Letters Written by Private George Morgan, 11th New Hampshire Infantry, Vividly Describing the Battle of Fredericksburg

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Six Civil War Letters Written by Private George Morgan, 11th New Hampshire Infantry, Vividly Describing the Battle of Fredericksburg

Lot of 6 letters written by Private George Morgan, Co. F, 11th New Hampshire Infantry, to his younger brother, Austin (1838-1919), at home on the family farm in Sutton, New Hampshire. George (1834-1864) enlisted in August of 1862, seemingly motivated more by the bounties offered at that time to fill state enlistment quotas than by noble aspirations of preserving the Union or abolishing slavery. The letters offered here span roughly George’s initial year of service, December 16, 1862-September 23, 1863, including his first engagement at the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 12-15, 1862. Over the course of the following year, George participated in General Ambrose Burnside’s infamous Mud March as well as a series of sieges, including those at Vicksburg, Jackson, and Knoxville.

The first letter comes from a camp in Virginia, where George writes to his brother just after the crushing Union defeat at Fredericksburg and reports on the action in and around the town: “We went over to the city last Friday morning. They bombarded the city. . . and drove the Rebels out. . . We lade [sic] by the side of the river that day and knight [sic]. . .so the shells went over us but some of them struck into the river. They killed one man. . .that belong to the 12th regt. There was a regt. A coming over the hill and the Rebels threw over and one struck right in among them and it lade [sic] out three. . . they carried them off in an ambulance. It is a hard business to see them killed. . . The next day was Saturday and we went into the battle about one o’clock and we stayed on the filed till after dark and then we went back down to the river. They carried off our wounded that knight [sic] and the dead lay there. Now they don’t dare to go and bury them. . . the bullets came nearer me than you would want. . . there is one shell that [threw] the dirt and mud all over me. The damn things whistled pretty close to me sometimes.”

In his next letter, written over the course of two weeks spent in both Mount Sterling and Winchester, Kentucky, where his regiment was stationed during its attachment to the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, 9th Army Corps, Department of Ohio that April. Morgan shares with his brother the details of the long trip from Newport News, Virginia to Kentucky, which took seven days and made them all a considerably “lamer set of boys.” In addition to marching, the 11th New Hampshire completed part of the journey by steamship, the John Rice, and by train, although not in very comfortable compartments: “We had come to there in damned old cattle cars. We went over the Allegheny Mountains and that was a dangerous looking place to ride. They went through one tunnel underground that was ¾ of a mile long . . . the snow was about six inches deep over the mountains.” Morgan shares the details of his passage from Covington to Cincinnati, Ohio by steamboat and writes with admiration for the surrounding landscape: “The land in this country is the best land that I ever see [sic]. They have large plantations and nice houses and they keep lots of [slaves].” The next movements of his regiment take him from Kentucky to Mississippi in June of 1863 for participation in the Sieges of Vicksburg and Jackson with the Army of the Tennessee. During the Siege of Vicksburg, on June 22, Morgan writes to his brother from Milldale, Mississippi, “within 12 or 15 miles of Vicksburg. We can hear the cannon plain from there.”

A year after he voluntarily enlisted, in August 1863, George writes to Austin from Nicholasville, Kentucky, counseling him against joining, despite his recent conscription: “I don’t feel so bad for you as I do for Father and Mother. But ever mind, I want you to stay there till I get home. You give them the three hundred dollars and tell them to go to Hell. I will be willing to pay it myself. If you come out here we should lose as much in one year as you would pay the three hundred. Three hundred dollars would not kill us half so quick as a damned bullet would.” After his experiences in battle, George clearly has reevaluated the merits of earning “easy money” through military service. His next two letters, dated September 12 and 23, 1863, reinforce these sentiments: “I want you to pay the three hundred dollars and tell them to stick it rite [sic] up their damn ass. . . They had no business to draft you. . . I think more of that old democret [sic] party than ever I did before. . . I shall advise every boddy [sic] else to keep out of this war just as long as you can. . . I have been [dragged] down until I could hardly go or stand and would give all that I have to get out of it free and clear.” New Hampshire draft registration records from June of 1863 indicate that Austin was counted as eligible for conscription, but the historical record yields little consistent evidence of his service.

Meanwhile, following a winter spent in eastern Tennessee with his regiment, George Morgan contracted a disease at Annapolis, Maryland and was hospitalized there in May. While his corps marched on to join Generals George Meade and Ulysses S. Grant in the Overland Campaign, Morgan stayed behind and was eventually transferred to a hospital in Philadelphia to continue his convalescence. Upon his recovery, he was detailed as a nurse during the spring and summer of 1864, working at the Chestnut Hill Hospital. That July, he was called away to assist with the defense of Washington, DC during the Confederate onslaught led by General Jubal Early. While in Washington, Morgan seemingly contracted diphtheria and was hospitalized once again in Alexandria, where he died on July 23, 1864. Records indicate that Austin, conversely, survived the war and became a wealthy farmer in New London, New Hampshire, owning over 1,000 acres of land on which he farmed crops and tended cattle and sheep.Letters with light toning and scattered areas of minor brown staining.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB