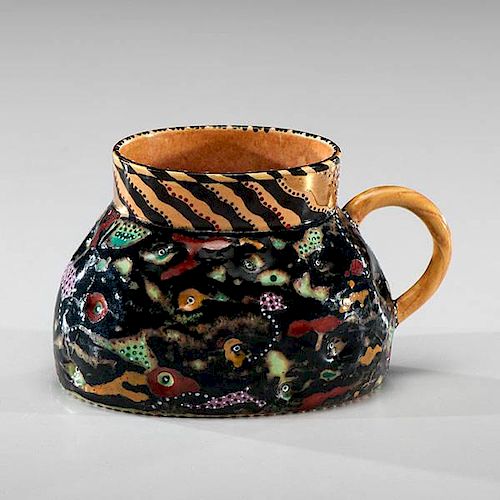

Ralph Bacerra (1938-2008; USA)

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

May 28, 2015 - May 29, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Luster Cup

1993

Porcelain; ht. 3, wd. 5, dp. 3 inches

Signed and dated, Bacerra '93, on base.

A star of post-WWII studio pottery, Ralph Bacerra’s dazzlingly work is prized both polychromatically and technically. His difficult, multi-firing method ensured that only works which emerged in immaculate condition could be shown; lesser items were dispatched to the shards pile. Subsequently, about half the pots he began ended up there. Of what remains, are superbly constructed and lusciously sensual pots and sculptures. But that is just what we came to expect of him. It was simply “what he did.” It kept getting better and we accepted that as well without much comment. Now that he has passed on we are realizing for the first time the magnificence of his legacy.

He represented the pinnacle of a certain approach to ceramics -- a master craftsman -- unapologetic about his love of process and impervious to pressures to make his work seem more “art-like” and conceptual. Simply stated, we have lost the most extraordinary decorative potter of the last fifty years. Initially, I was hesitant to make this claim so boldly but the more I thought about it the more I realized that it was an unassailable statement. Yes, America has produced many masters of decoration in the past half century. But it is no insult to any of them to say that Bacerra’s vast multi-facetted oeuvre stands in a class alone. Bacerra described his goals modestly and unfashionably, “I am not making any statements — social, political, conceptual, or even intellectual. There is no meaning or metaphor. I am committed more to the idea of pure beauty. When it is finished, the piece should be like an ornament, exquisitely beautiful.”

This statement dovetails perfectly with the writing of Amy Goldin, the critical voice of the Pattern and Decoration painting movement during the 1970s, when she argued that “decoration can be intellectually empty but that does not mean that it has to be stupid.” Indeed, Bacerra’s vessels bristle with intelligence but of the visual sort; layered planes both receding and advancing, interlocking patterns, and graceful but contemporary appropriation of Japanese Imari, Kutani and Nabeshima porcelain. But given his vocal skepticism of the artworld, it is surprising that even Andy Warhol’s work was a strong influence. A print from the pop artist’s flower series was the first thing one saw when entering the foyer of Bacerra’s home. If one spoke of his “art,” Bacerra would argue that it was nothing more than quality craft with some science thrown in for good effect. That is true but not complete. What he achieved bordered on the magic of alchemy.

Provenance: Gifted Directly from the Artist - Shipping Info

-

The buyer is solely responsible for shipping charges related to auction items. Cowan's will make a recommendation for a local shipping agent; however, the buyer shall be responsible for contacting the agent and making necessary arrangements. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

Cowan's recommends the following local shippers to handle purchases:

The Neighborhood Office8440 East Washington StreetChagrin Falls, Ohio 44023Phone: 440-708-0101

Fax: 440-708-0102

UPS store

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB