Naturalist John H. McIlvain, Letters and Journal Written While Visiting the American West, Incl. Fort Laramie, Ca 1853

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Feb 21, 2017 - Feb 22, 2017

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

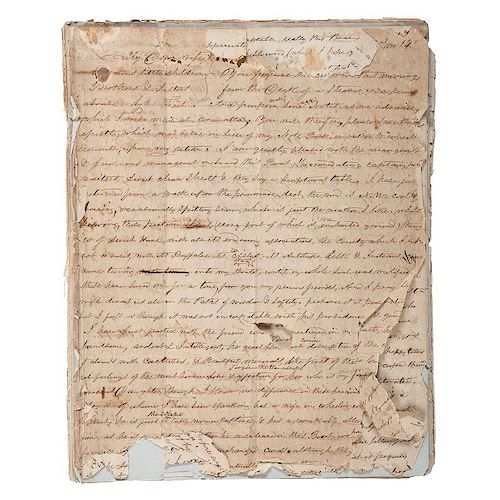

Lot of 6, including: 47 pp journal of Quaker and self-taught naturalist John H. McIlvain documenting his first journey "Far West" to Fort Laramie from March 1853 until June 1853, and five, 7 x 11 in. photographs of various buildings at Fort Laramie taken in 1931, each stamped on the reverse W.W. Scott, Omaha, Nebraska and inscribed by a previous owner.

An antiquarian of sorts, John M. McIlvain was a Quaker, lumber mill owner, self-educated ornithologist, and naturalist. McIlvain's interests directed him towards the American West, to Fort Laramie and other western forts, to live and study with American Indians. Two years before his visit, the American government and some Plains Indian chiefs agreed upon the first installment of the Fort Laramie Treaty that attempted to end tribal rivalries and permit travelers and railroad workers on the Platte River Road. The government allocated territory to tribes and installed head chiefs to ineffective councils, but the treaty failed when the United States government seized back the land in the 1860s after the discovery of gold in the area. McIlvain, however, visited Fort Laramie and the surrounding plains during a relatively peaceful time in the spring of 1853.

Suited to the comforts of urban life in Philadelphia, the journey West was physically and socially hard for McIlvain. He struggled to find his place within the small cohort of people travelling with him. He wrote often about his loneliness and the snickering of members of his traveling companions or Western settlers in taverns and trade depots. Like his culture, he had a difficult time being accepted into American Indian society. Having little to no prior study or knowledge of American Indian customs, he called tepees sinew tents and believed that he could communicate with American Indians by signs...universal among the tribes that did not exist (June 1853?). Still, he was very intrigued by American Indians and disgusted by the low ebb of morality of settlers who sometimes poisoned starving Shawnee and Windolts(?) like unwanted vermin (Kansas, April 14, 1853). He described American Indian languages as the most soft and plaintive of any [he] ever heard and was amused by women slinging their infants in their papooses (Kansas, April 14, 1853). Despite his original plans to live with American Indians, he spent more time at various military posts. He did stay with a kind-hearted Kansas man in his wigwam for a few nights. During his travels, he made one friend, the chaplain at Fort Laramie who shared similar interests. The two went on various ornithological expeditions, acquiring a wide variety of specimens that would eventually be in displayed in McIlvain’s house museum in Philadelphia. One item he obtained for his collection was not a bird, but a bloody arrow pulled from the body of a soldier who died during a minor altercation with a local tribe.

A strange man in American Indian and Western society, McIlvain felt most welcomed in nature. He marveled at the surrounding scenery, especially around the Platte River. After visiting the Platte, he wrote:

[It] is one of the most beautiful streams I ever beheld; like most others in this land, it is sparsely timbered, although intervals occur for a distance of 100 miles, in which there is no wood. Its banks are generally low, different in this respect widely from [illegible]...although the channel is rapid, it is almost everywhere fordable, its width is from 1 to 1 1/2 miles. A range of bluffs extend on either side, sometimes running parallel....You approach one of these bluffs imagining it to be half a mile distant, but find after traveling for an hour that you are as remote as when you set out. Where you first strike the Platt [sic] these elevations greatly resemble those in the vicinity of the beach or ocean and are of a yellowish sand, but as you advance with an almost continuous upward gradation, these become grand and awfully sublime...Oh did I posses the painter's art, or the poet's lyre, how would I transfer to the canvas with indelible, truthfulness or portray with eloquence the rhapsody of [all this] (Fort Laramie, June 10, 1853).

While traveling near the river, he happened upon a herd of 200 Buffalo, and proceeded to hunt.

The body of the herd had encamped over the bluffs but 3 or 4 had been separated from them, two of which, enormous Bulls, were making their way towards me. They ran within 45 yards perceived them and making a bound onwards then over a ditch, landed me upon his neck. Instantly adjusting myself I attempted to fire but he was restive and I could not [handle] my heavy rifle with precision...onward he bounded like an antelope...an enormous bull of at least 1,500 pounds...shaking his sides,...his tongue out,...snorting like a porpoise...I attempted to shoot but to my dismay my pistol had jumped from its holster...a gentleman in the rear had witnessed my discomfort and picked up the weapon [but did not shoot the beast]...If I live to return, I fancy I shall be able to relate some thrilling stories (Fort Laramie, June 10, 1853).

As much as he reveled in the beauty of the area, there was still some ugliness. En route to another fort, he wrote:

...[the land] is of barren interest, no grass for our horses, nor wood, nor water except from filthy ponds...and that has a tendency to depress the spirits of the numerous unfortunate emigrants among whom especially last year, cholera have made sad ravages...there is hardly a day passes that we do not meet 8 or 10 of those graves...they had generally been interred within a short distance of the road with a piece of board at the head and foot...several times our French cook has removed those tokens of friendship to kindle the camp fire. The other day while eating...one of these memorials with the name and age of the departed, lay upon the burning embers and I could not forbear reproving him...surely, I said to myself it is hard thus to leave life without the sympathy and the kinds words of those [left behind] (Fort Carney, May 5, 1853).

McIlvain began his journey back home with a group of French buffalo hide traders. Later, he rejoined some of the officers he met at the fort. Along the way, he bartered for more trinkets along trade routes. For a short time, he and the officers lodged with a small group of Pawnee (August 1853).

Much better suited in Philadelphia, McIlvain rejoined his friends with similar interests and peculiarities who marveled at his expeditions. He returned to Fort Laramie on several occasions until his death in 1882. At the time of McIlvain's passing, the Friends’ Intelligencer and Journal published a brief article about his life and collection:

“A sincere friend of the Indian Race, whose original character he deemed both noble and truthful, he made several visits to their reservations in what was then considered the 'Far West,' and remained among them for months at a time, always parting with them with friendly feelings on both sides. Frequently when a delegation passed through Philadelphia, on their way to Washington, or on their return, he managed to interest the whole party sufficiently to induce them to visit him at his house...The valuable museum of objects related to their customs and dress, which he has left, shows many mementos of their appreciation to his kindly attention” (197, 198).

McIlvain's family auctioned off the contents of the museum three years after his death through Thomas Birch's Sons.

The journal is accompanied by a transcription as well as supplementary research concerning McIlvain and the officers he encountered at Fort Laramie.

Provenance: N. Flayderman and Co., Inc.The journal is in poor condition without a cover and with many damaged pages. McIlvain writes to his wife that it was very damaged during his travels, implying that it was in poor condition in the 1850s. The letters have typical folds and toning, his writing can be hard to read at times because he often wrote while traveling on whatever surface was available.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB