Myles Keogh, Collection of Letters Written by Acquaintances

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 21, 2014 - Nov 22, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

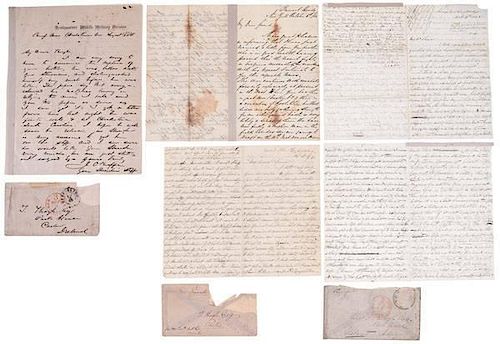

Myles Keogh, Collection of Letters Written by Acquaintances

12 documents, many with covers.

This Civil War-date and post-war archive, written by relatives and friends of Capt. Myles Keogh, includes some long and detailed letters chronicling the lives of the Irish immigrants who fought in the Union Army.

Authors include Joseph O'Keefe and Daniel Joseph Keily, who served with Keogh in the Papal Army in 1860. They were recruited into the Union Army together as captains.

Two letters by O'Keefe to Keogh's brother in Ireland bring the news of Keogh's capture on General Stoneman's failed raid to liberate Federal prisoners in Andersonville. In a letter dated August 30, 1864, on Head Quarters Middle Military Division letterhead, O'Keefe writes:

My dear Keogh,

I am very sorry to have to announce the capture of your brother. He was taken with Gen Stoneman, and distinguished himself very much before he was taken. The papers say that everyone admired his reckless bravery in rallying the men… I got a letter from him last night. He was quite well & at Charleston South Carolina. I hope he will soon be released. Gen Sheridan is very anxious to get him on his staff and I am sure he would like Gen Sheridan very much.

On September 17, 1864, he writes that he has contacted his uncle, the Bishop of Cork, to see if he can intercede with the Bishop of Charleston, SC, in effecting Keogh's release.

Keily, serving as chief of staff for General Shields, writes that Myles came through Antietam OK, noting we have fully a million men in the field besides they are going to draft on the 10th inst 300,000 men more to be kept in reserve. The issue of the struggle therefore can be no longer doubtful. The South is completely exhausted in men, money, & material.

Two cousins of Keogh, Dan Keogh O'Sullivan and Richard Keogh, came to America in the summer of 1863. Myles used his influence to place them in volunteer positions in the Union Army, while paying for their expenses.

O'Sullivan, serving as a volunteer on General William French's staff, writes home about his adventures: Some hard fighting during the last ten days. I had my share of it with the Guerillas. He was leading a small baggage train when fifty mounted partisans attacked, Standing their ground, the escort's gunfire alerted a nearby Federal cavalry patrol, who rode to the rescue. He also mentions hazards of another sort: If Tom were here he could satisfy his thirst on nig[g]er women. I met one in Warrington yesterday a brunett(?) dressed in white with long yet black curls flowing down to her waist… They keep near the camps, however I keep wide of them.

He tells Thomas Keogh, Myles' brother, Ireland is the land of saints; remain there for your soul's sake.

In January 1864, O'Sullivan got a job as a recruiting officer for Col. Keily, with the promise of a Lieutenant's commission if he signed up 42 men in thirty days... in Natchez, MS! Until then, he wouldn't be paid. In a detailed, 10pp letter home, he describes his time in America, recording the hardship of trying to find a job as an Irishman. While he extolls the beauty of Natchez and the female population, he is worried, because the Rebels are "in great force" about six miles from town: [w]e cannot tell at what minute they may attack. I hope they won’t mind it, as the troops stationed here are principally Colored, and I don’t know how they would act if the enemy attacked by night.

General John Buford had died just a couple of weeks before this letter was written. O'Sullivan writes: Poor Myles, Gen Buford’s death was a great blow to him.

About the same time, Richard Keogh writes home from the Shenandoah Valley, where he is serving under Sheridan: You must have heard of Buford’s death… I had a letter from Myles a few days after saying he would come out to this army to see after his horses and that he would come see me. He was greatly put about. He attended B till at last died in his arms. He was in Washington when he wrote.

The only postwar letter is by Richard, dated April 28, 1866, from Chicago. In it, he gives Thomas Keogh advice on real estate, telling him to look into rental property in the city instead of buying farmland and working it, and relating a rather simplistic view of the plantation system in the South:

The Southerners were the people that made by land in this country on account of the slave trade. They had their labor for nothing, had 4 or 5 hundred of those niggers working for them and a crop of young niggers every year the same as you will have your lambs next spring. Sold those at from 1000 to 3000 $ a head at 8 or 10 years old… They had magnificent dwellings, but now they are impoverished....

Myles Keogh (1840-1876) was a famous Irish-born cavalry officer of the U.S. Civil War and subsequent Indian Wars. While serving in the Valley under Shields, he came within minutes of capturing the famous Rebel general "Stonewall" Jackson at the battle of Port Republic. The most trusted of General John Buford's staff, Keogh was part of the cavalry vanguard that prevented A.P. Hill's Confederates from seizing the high ground at the start of the battle of Gettysburg. When Buford fell ill after the battle, it was Keogh who cared for him, up to his death.

Despite his fame in the Civil War, Keogh is perhaps best known as leading Co. "I" U.S. 7th Cavalry in its last stand at Little Big Horn. Separated from the main group, which was led by Custer, Keogh and his surrounded men fought overwhelming odds until they were cut down to a man. The Indians did not mutilate Keogh's body as they did many others. This is attributed to the Papal medal he wore around his neck, from his service in the army of Pope Pius IX in 1860. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB