M.C. Foote, Archive Documenting Duties as Commander of the Spotted Tail Agency, Featuring 1876 Indian Census Books

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 12, 2015 - Jun 13, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Lot of 15 letters, plus, and three handmade(?) booklets with counts of Indians at the Spotted Tail Agency.

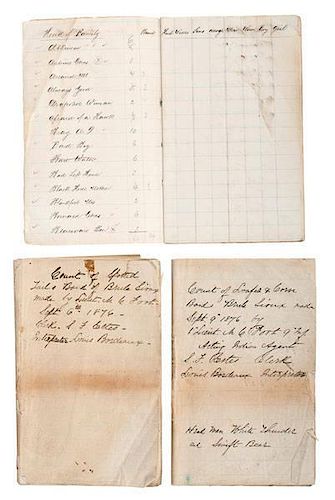

Books each 4 x 6.25 in, lined, no covers. One with manuscript note on front: Count of Spotted Tail's Band of Brule Sioux made by Lieut. M.C. Foote / Sept. 6th 1876 / Clerk - S.F. Estes / Interpreter - Louis Bordeaux. Small one with no notes on first page. Third one with: Count of Loafer & Corn Bands Brule Sioux made Sept 9th 1876 by 1st Lieut M.C. Foote 9th Inf. / Acting Indian Agent / S.F. Estes Clerk / Louis Bordeaux Interpreter / Head Men White Thunder and Swift Bear. Counts made by head of family; he then gives Men, Women, Boys, Girls, Babies, Total. Family heads are sometimes widows, which he notes. Spotted Tail's family consists of 22 people, with 4 women, 9 boys and 8 girls. The total for Spotted Tail's Band, is 2593 in 342 lodges (averaging just over 7.5 per lodge). The count of the other two bands are a bit unclear, but he gives the subtotal for each of the two bands, 621 and 728, for a total of 1349.

He notes in a letter to his former professor, Othniel Charles Marsh, at Yale College [Sept. 17, 1876] I went into every lodge with a clerk and interpreter who knew all the Indians here. I saw nearly every one myself and found a total of 5614 men women & children. This no. includes about 28 white men & their Indian families who draw rations under the treaty of 1868, and 148 Indians who have been transferred from Red Cloud Agency in the last month....The former agent here Mr. Howard, transferred a list to me of 9135, he had been issuing rations on that basis, and told me his predecessor estimated the no. much more than that, I think twice as many. ...So these Indians have been increased - "on paper" - since the Agency was removed to this remote region where outside parties, interlopers, meddlers, and falsifiers such as Professors of colleges, scientific gentlemen, army officers &c., could not have a chance to interfere with the legitimate business of the much abused ans slandered agents and their employers of the "Ring." He goes on to says that the situation seems to be the same at the Red Cloud Agency - 10,000 on the books, between 4 and 5,000 at the agency.

A "true copy" of a telegram from Omaha, July 20, 1876: By the direction of the General of the Army, and at the request of the Secretary of the Interior, who has dismissed the agent at Spotted Tail Agency, the instructions of the Lieut. General are that you take charge of, or designate some good officer to take charge of the Spotted Tail Agency and property thereat temporarily, and perform the duties required until a civil agent is again appointed who will be instructed by the Secretary of the Interior to act subordinate to the military commander until close of hostilities.... you will cause to be made an accurate list of all Indians now at the Agency and issues will be made to these and no others. You will prevent as far as possible any Indians from leaving,...

Lieut. Foote, of course, received this appointment. As part of his census of residents, he took note of others also present [Aug. 15, 1876]: ...I find at this agency a list of about six hundred (600) white men and half breeds with their Indian families, drawing rations. A large number of these men are perfectly well able to support themselves. Some of them are what is termed "Treaty Men" and claim rations under the provisions of the treaty of 1868. I fail to see anything in the treaty that provides for their maintenance...I would respectfully request authority to drop from the list such men, with their families, as I know are working for good wages or have sufficient means to support themselves. He goes on to name several and their sources of income.

Three documents in the group relate to supplies purchased or received at the agency. At every turn, Foote finds conflicts in the amounts received, issued, etc. by his predecessor. Four documents indicate differences in the records examined by the Indian Office and Treasury Department. A long letter dated Dec. 5, 1878 gives Foote's overview of the entire experience as Acting Indian Agent.

In late October 1876, Order No. 3 relieved Foote from duty as Acting Indian Agent. A few days later [Nov. 1, 1876] he received a letter from R. McKenzie saying that he allowed Foote to rejoin his company because ...from what I heard I judge your health would not allow of your going in the field and I thought your service at Spotted Tail very valuable...

The final letter in the group is from S. Leindenberger, an employee from Spotted Tail Agency, Sept. 19, 1877. He notes: The excitement caused by Crazy Horse's death is now over, we go an accession of about 1100 Indians which ran away from Red Cloud Agency and which will remain here now making the total 8800 persons. After surrendering at Fort Robinson, Crazy Horse tried to live in peace with Americans. But reportedly he was asked to help round up the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph who had left their reservation and were headed to Canada. Crazy Horse refused, then relented. A number of misinterpreted messages led General Crook to order his arrest, but Crazy Horse had fled to Spotted Tail with his sick wife. As he was returning to Fort Robinson with Jessie Lee (the transcriber of the telegram above), then Indian agent at Spotted Tail, along with other Indians. In the ensuing confusion about turning Crazy Horse over and to whom, Crazy Horse was stabbed with a bayonet by one of the guards and died near midnight in the care of post surgeon, Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy. Any death of a "big man" raises questions, and this one was no exception. It seems to have taken Foote some time to convince Washington that he was not cheating the Indians or the government out of supplies for the Agency. Scandals were rife at the time. Population numbers were inflated so more supplies were needed, but when accounts of issued rations were examined, generally less than half of the promised rations were delivered. Since probably half as many people were living at the agency as some claimed, and they only received half of their rations, this leaves about 3/4 of the rations unaccounted for. Another level of Indian Agent scandals was mentioned in Foote's letter to Prof. Marsh - the Indian Ring scandal. William Belknap convinced Congress to allow him alone to appoint sutlers and traders to supply army forts and Indian agencies. Belknap would then receive a kickback from those traders. Just another scandal for the Grant administration...Although profiting from Indian rations pre- and post-dates Grant. It appears to have been universal.

The Morris Cooper Foote Collection

Lots 140-152

Cowan’s is pleased to offer an important collection spanning 40 years of material—40 years of the life of the soldier Morris Cooper Foote, great grandson of Lewis Morris—a signer of the Declaration of Independence—and great nephew of novelist James Fenimore Cooper.

When the Civil War began, Foote joined the army at the age of 17 in his home state of New York, where he mustered into the 44th NY Volunteers, a group that came to be known as Ellsworth’s Avengers. After a promotion to 2nd Lieutenant and a transfer to the 92nd New York Volunteer Infantry, Foote was captured by the Confederate Army at the Battle of Plymouth in 1864 and was sent to Libby Prison. Eventually, Foote and many other POWs were sent to Charleston, S.C. where both Confederate and Federal forces attempted to use prisoners as human shields to discourage shelling—an incident now known as the “Immortal 600.” As one of the Federal officers placed under the fire of the northern batteries at Charleston, S.C., he was the only one wounded. From Charleston, Foote was transferred to Camp Sorghum in Columbia, South Carolina, where he escaped. He later published the story of his escape and loved to share it with family and friends. In the concluding stages of the war, he served as a staff officer at the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox.

After the Civil War, Foote entered the 9th U.S. Infantry on May 1866, and on March 7, 1867, received a promotion to the first lieutenancy. He served with his regiment in California, Alaska, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska. In Alaska, he commanded one of the two companies that received the territory from Russia in 1867. Foote also served in Native American campaigns and expeditions under Generals Miles and Crook, in Wyoming, New Mexico and Arizona. As part of Foote’s time in Wyoming, he took part in the exploration of The Black Hills a year before the events of Little Big Horn. He also conducted the first census of the Sioux Indians after the 1876 treaty as part of his duties as the commanding officer at the Spotted Tail Agency. After the discovery of gold in the Black Hills—an event that caused controversy between miners and Indians and eventually lead to tragedy—Foote attended a meeting of miners who, deciding to leave the area as requested after hearing a resolution from the President of the United States, went on to create Custer City (present day Custer), South Dakota, now considered to be the oldest town established by European Americans in the Black Hills. On January 26, 1883, Foote achieved the rank of captain of the 9th infantry. In September 1886, he witnessed the surrender of the Apache chief Geronimo to General Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona.

Following the end of the Indian Wars, Foote’s regiment participated in the Spanish-American War. Foote commanded a battalion at the battle of San Juan Hill. At the formal surrender of Santiago, the commanding officer General Shafter selected the 9th infantry to receive the surrender of the city and province where Foote commanded a company stationed in the plaza. In August 1898, Foote received promotion to the rank of Major and orders to Boston on recruiting service, being unable to rejoin his regiment at the time due to suffering from Cuban malarial fever.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the U.S. Army dispatched the 9th Infantry Regiment to China during the Boxer Rebellion and the China Relief Expedition, where Maj. Foote took part in the Battle of Tientsin.

After being appointed a Brigadier General on February 18, 1903, Foote retired the following day. Foote retired to Europe and resided in Geneva for two years. At the Hotel d’Angleterre, after recovering from double pneumonia and double pleurisy he passed away of heart failure on December 6, 1905.

As a soldier and an officer, Morris Cooper Foote experienced first-hand the moments that shaped our history and set the stage for the 20th century. This exceptional collection includes diaries, journals, letters, documents, books, photos, maps, prints, personal belongings, and more pertaining to his professional and personal life.Some wear to the booklets' outer pages, otherwise fine. Letters are for the most part excellent.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB