M.C. Foote, 9th US Infantry, Archive Documenting Military Service Including Spanish American War, 1886-1900, Featuring First-Hand Account of Participa

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 12, 2015 - Jun 13, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Lot includes 2 journals, 2 books containing approx. 140 General Orders & Circulars from 1898, and 10+ loose letters and documents.

The Spanish-American War originated in the struggle of Cuba and other Spanish holdings in the New World for independence. Although the proximate revolt in Cuba began in February 1895, it was mostly Spain's brutal repression (and its portrayal in the media, of course) of the Cuban efforts that got the sympathy of ordinary Americans. The USS Maine was sent to protect American interests. When the Maine sunk in Havana Harbor (probably the result of an explosion in her magazine, not a result of a Spanish attack, as was thought at the time), Americans demanded action. Congress declared war on April 24, retroactive to April 21. Spain was entirely unprepared, and, being more distant from Cuba than America was, was unable to get her troops and navy to Cuba in time. Commodore Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, while Gen. William Shafter landed east of Santiago and advanced on the city to force the fleet out of the harbor. Santiago surrendered on July 17, although a formal treaty would take several more months. Captain Morris C. Foote was on San Juan Hill, outside the city of Santiago, with Theodore Roosevelt's "Rough Riders" and others through the action.

This lots consists of a couple of private journals, one with Private Journal. From January 1, 1888, to April 31, 1896. Captain Morris C. Foote, U.S. Army. and Private Journal From May 1st 1896 to October 20th 1900 Captain Morris C. Foote, U.S. Army. Approx. 8 x 10 in. For the most part the entries are fairly mundane, notes about letters written and received, bills paid, etc. These journals trace his courtship and wedding to Annie Murphy:

1895 / Sat. 16th (June) Col. Richard Dodge died at 3.30 this morning. Wrote Russell.

1890 / Nov. 10, 11, 13, 14, 145, 16 – called on Annie

1890 / Dec. 12 Cold. Army Building, two cases. Bought ring for Annie. Dined at Theo. Keese’s.

Sat. 13th: Army Building, one case. Had Annie’s ring sent to her to look at.

1891 / March Tues. 24th Announced my engagement letter from Annie

April 29th: Married at 12m. to Miss Annie Elizabeth Murphy, daughter of D.F. & A.E. Murphy, at their residence, 314 C. Street N.W., by the Rev. Wm. F. Marshall assisted by the Rev. W.R. Cowardin SJ. Left Washington at 2.0 PM. Went to Baltimore Rennert House.

Sept. 3, [1892] – Very fine. Paid bills. Inspection in full dress. President Harrison came through en route to Loon Lake, paid my respects to him.

1894 / March 20th - …my dear wife was safely delivered of a fine boy

A couple notes include Civil War retrospectives:

April 6th(1894) – Windy. Wrote Mr. Murphy. Lyceum. 29 years ago today I was in the battle of Sailors Creek where Ewells Corps of Lee’s Army was destroyed, the last pitched battle of the Army of the Potomac & the Army of Northern Virginia

April 9th: 29 years ago today the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered to the Army of the Potomac.

1895 / Sat. 16th (June) Col. Richard Dodge died at 3.30 this morning. Wrote Russell.

1898 – June 7th, Wrote Annie twice. Hot. Order to move came at 9 p.m. packed and sat up all night

Wed. 8th Marched out of camp at 3.20 this morning. Took cars and went to Port Tampa. Went on board transport Santiago at 8.30 am. Wrote Annie & sent telegram.

June 20th Fine. Near the land this morning. Lay off the mouth of the harbor of Santiago all day. Could see the Morro Castle at the entrance. Towards eveng. Steamed out to sea about 25 miles.

They returned the following day, and lay off the harbor all day again. The regt. landed about the 25th.

July 1st Friday. Rations issued this morning. Newspaper mail. Broke camp about 8 a.m. Marched to the front, slowly on account of frequent halts. Hzard [sic?] artillery firing. Under fire about 10 a.m. Had to walk over the men of the 71st N.Y. Volunteers to get to the front. The regiment was ordered forward moving by the flank on a narrow road. I commanded the leading Co. H, we were under severe fire all the time both shrapnel and infty. Fire, sharpshooters seemed to be in our front and flanks, hidden in trees and in the dense chaparral. I crossed the San Juan river at the head of my company and formed in an open field to the left of the crossing, finding some of the 13th and 24th infty mixed there with me. When I crossed I infer that our forward movement was delayed for a while as the 2nd platoon of my Co. did not follow at once, and no other co. of the Regt. Came over then except a part of Co. C, the 2nd Co. of the 1st battalion. I sent back for the rest of my Co which joined me, under the 1st Sergt. We opened fire on the enemy on the hill in our front, until an order to cease firing was passed along the line. I then formed my Co ready to advance and an officer, who said he was an aid to Gen. Hawkins, said that the General wished all the troops to move forward. I said that I did not like to move without any orders from my Battalion or Regimental Commander, but after a few minutes this officer came and repeated the order to move forward and I did so, directing my advance on the Black House, or Fort on the top of the hill in front. A few men of the 24th Infty joined the right of my Co but most of this regt seemed to be on my left. I moved in open order, as rapidly as possible, across the open field and up the hill. I found Lt. Simpson, act. Adjt. Gen of our brigade, well up on the hill, he helped me cut the wire fence so my co could pass through. As I paned on to the crest the enemy seemed to be retreating. I could see some of the companies of my regiment coming up on my right and rear. My company was the first one of the regiment up on the hill at the fort. I then placed my men on the crest of the hill to the left of the fort and opened fire on the retreating enemy. As the Regt formed up on the crest my co. was placed on the left. We held this position and at dark entrenched ourselves working all night. The casualties in my co. were as follows: killed none, wounded one Corporal and four privates. I was placed in command of the 2nd Battalion as soon as the Regt was formed on the crest of San Juan Hill. We received some hard bread and bacon during the night, and some ammunition. We sent detachments back and got some of our blanket rolls and haversacks.

July 2nd Saturday Firing commenced at daybreak, and continued all day strengthened our position at night by continued work in the trenches, bivouacked just in rear of them, and in them. Heavy night attack….

Things quiet down the next day. They stay in the trenches for a time.

July 17th Sunday. “Our Regiment” marched into the city this morning and paraded to receive the formal surrender of the Spanish command. We formed in the plaza facing the Governor’s palace, as the old cathedral clock struck twelve o’clock our flag was raised over the palace, one regiment presented arms, and the band played the star spangled banner. We remained in the city, the only regiment there.

There is a long summary of the battle (might have been for a talk). In it he notes that most of the forces were regulars where he was. The only volunteers were the 71st NY and 2nd Mass. And 1st US Vol. Cavalry, known as “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.” There were very few volunteer troops ready to ship out when they reached Tampa. He goes on to talk about how disorganized these “raw” troops were, and how well trained his “regulars” were.

The night of the 1st of July found the 1st division of the 5th Corps literally hanging on to the ridges of the San Juan hills with nothing but their rifles and what ammunition they had in their belts, 1500 men lay dead and wounded on the slopes, and in the chaparral, and Santiago was not taken. When we went into action that morning we had stripped for the fight, that is we had divested ourselves of our blanket rolls, haversacks, and everything except our arms ammunition and canteens. Most of us had waded waist deep in the river and we were wet, cold, tired, and hungry. We knew we had to strengthen our position and cover ourselves with hasty entrenchments that night or the ridge would be untenable the next day. Consequently details were made and all through the night work was kept up, at first we had nothing to dig with but bayonets, tin cups, and hands, but about midnight a few picks and shovels were brought up by parties sent down after water and the haversacks we had taken off in the morning. Sometime in the night a pack mule train came up and left a few boxes of hard bread and some ammunition at the foot of the hill. We carried that up and distributed it. At day break the enemy opened a furious fire on us but we were pretty well under cover then and our losses were very slight. All that day the firing continued, but slackened up toward evening so we could take the men out of the trenches and let them make coffee and fry bacon. That night we resumed work on our entrenchments and put them in very good shape. The next day firing began at dawn as usual but ceased about noon when General Shafter made the first demand for the surrender of the city. After that holding our position was simply a matter of endurance on the part of our troops. We actually lived from hand to mouth as we never had a days rations ahead. The pack mule train came up each night with a little hard bread, bacon coffee and sugar, this was issued out in the morning and consumed that day. The broiling hot sun shone on us and the tropical rain storms beat down upon us, we laid on the wet ground at night and got such rest as we could. Finally when negotiations for the surrender of the Spanish forces were completed on the 17th of July, and we took possession of the city the pernicious malarial fever of that country had attacked us and in a few days half our force, officers and men, were completely disabled. This condition of affairs grew worse until at last, after a statement of the condition of the troops – miscalled a round robin – was made and signed by all the Brigade and Division Commanders, and the ranking medical officers, the Fifth Corps, or what was left of it able to move, was embarked on transports and taken north to Montauk Point.

Had extended leave of absence in late 1899 for malaria (?), and 1900 saw him in China (see next lot).

The lot also includes covers of Official Army Register for January 1892, and 1902, with owner's signatures of Morris C. Foote and Mrs. Foote. Plus a 4 x 15.5 in. sheet with Stations of Regiments, with manuscript Feb. 25th 1899 written at top. In the Infantry section, the 9th infy. Is listed as Entire regiment at Madison Barracks, N.Y. Ordered to the Department of California to be in readiness for service at Manila. Apparently that order was changed, as the 9th headed to Santiago, Cuba.

One penciled sheet appears to be a draft or notes for a summary of Foote's service up to mid-1899. The summary is manuscript in ink on "Recruiting Station, Boston" letterhead. A letter dated Nov. 18, 1900 from his son, Francis, also accompanies the archive.

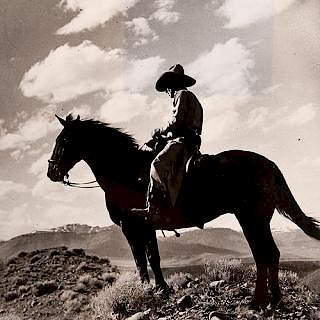

The Morris Cooper Foote Collection

Lots 140-152

Cowan’s is pleased to offer an important collection spanning 40 years of material—40 years of the life of the soldier Morris Cooper Foote, great grandson of Lewis Morris—a signer of the Declaration of Independence—and great nephew of novelist James Fenimore Cooper.

When the Civil War began, Foote joined the army at the age of 17 in his home state of New York, where he mustered into the 44th NY Volunteers, a group that came to be known as Ellsworth’s Avengers. After a promotion to 2nd Lieutenant and a transfer to the 92nd New York Volunteer Infantry, Foote was captured by the Confederate Army at the Battle of Plymouth in 1864 and was sent to Libby Prison. Eventually, Foote and many other POWs were sent to Charleston, S.C. where both Confederate and Federal forces attempted to use prisoners as human shields to discourage shelling—an incident now known as the “Immortal 600.” As one of the Federal officers placed under the fire of the northern batteries at Charleston, S.C., he was the only one wounded. From Charleston, Foote was transferred to Camp Sorghum in Columbia, South Carolina, where he escaped. He later published the story of his escape and loved to share it with family and friends. In the concluding stages of the war, he served as a staff officer at the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox.

After the Civil War, Foote entered the 9th U.S. Infantry on May 1866, and on March 7, 1867, received a promotion to the first lieutenancy. He served with his regiment in California, Alaska, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska. In Alaska, he commanded one of the two companies that received the territory from Russia in 1867. Foote also served in Native American campaigns and expeditions under Generals Miles and Crook, in Wyoming, New Mexico and Arizona. As part of Foote’s time in Wyoming, he took part in the exploration of The Black Hills a year before the events of Little Big Horn. He also conducted the first census of the Sioux Indians after the 1876 treaty as part of his duties as the commanding officer at the Spotted Tail Agency. After the discovery of gold in the Black Hills—an event that caused controversy between miners and Indians and eventually lead to tragedy—Foote attended a meeting of miners who, deciding to leave the area as requested after hearing a resolution from the President of the United States, went on to create Custer City (present day Custer), South Dakota, now considered to be the oldest town established by European Americans in the Black Hills. On January 26, 1883, Foote achieved the rank of captain of the 9th infantry. In September 1886, he witnessed the surrender of the Apache chief Geronimo to General Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona.

Following the end of the Indian Wars, Foote’s regiment participated in the Spanish-American War. Foote commanded a battalion at the battle of San Juan Hill. At the formal surrender of Santiago, the commanding officer General Shafter selected the 9th infantry to receive the surrender of the city and province where Foote commanded a company stationed in the plaza. In August 1898, Foote received promotion to the rank of Major and orders to Boston on recruiting service, being unable to rejoin his regiment at the time due to suffering from Cuban malarial fever.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the U.S. Army dispatched the 9th Infantry Regiment to China during the Boxer Rebellion and the China Relief Expedition, where Maj. Foote took part in the Battle of Tientsin.

After being appointed a Brigadier General on February 18, 1903, Foote retired the following day. Foote retired to Europe and resided in Geneva for two years. At the Hotel d’Angleterre, after recovering from double pneumonia and double pleurisy he passed away of heart failure on December 6, 1905.

As a soldier and an officer, Morris Cooper Foote experienced first-hand the moments that shaped our history and set the stage for the 20th century. This exceptional collection includes diaries, journals, letters, documents, books, photos, maps, prints, personal belongings, and more pertaining to his professional and personal life. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB