Lt. Colonel Frederick Schneider, 2nd Michigan Infantry, WIA and POW, Letters Written from Libby and Danville Prisons, Plus Related Belongings

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 20, 2015 - Nov 21, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

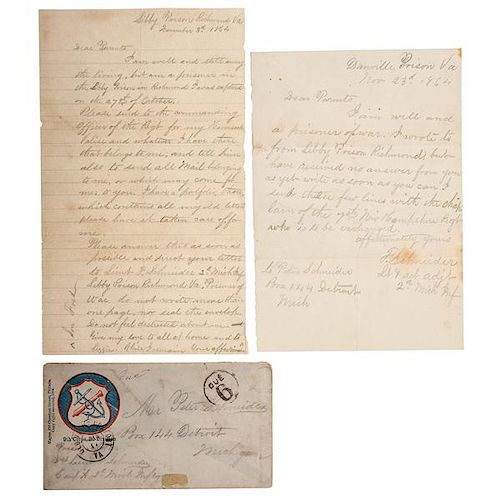

Lt. Colonel Frederick Schneider, 2nd Michigan Infantry, WIA and POW, Letters Written from Libby and Danville Prisons, Plus Related Belongings

Small collection of Civil War and post-war memorabilia of Col. Frederick Schneider and family, including two Civil War-date letters, written from the notorious Libby and Danville POW camps, November 1864; a Muster Roll; printed broadside for the play Union Spy, in which Schneider played a role; 15 clippings from various publications, mainly pictures of identified members of the Michigan 2nd Infantry; 11 photos of family members, the family home, and other unknown locations. Also included is what appears to be a draft letter authored by Schneider’s surviving daughter Elizabeth Helen, outlining the history of their home with information about the colonel and family.

Frederick Schneider was born in Saline, MI, November 24,1840, son of Peter and Mary Ruehle Schneider. The elder Schneider was a farmer and local businessman who moved his family to Detroit when Frederick was three. After graduating from Bryant and Stratton's Commercial College, he went to work as a shipping clerk and traveling agent for a wholesale grocer in Chicago.

With Lincoln’s first call for troops, Schneider enlisted as a private on April 18,1861 for a three-month term. Having had earlier military training, he was promoted to corporal and then sergeant in short order. He was mustered into U.S. service as a sergeant on May 25, 1861 with the 2nd Michigan Infantry.

Schneider served with this regiment throughout the war. He was wounded twice in battle, and seriously injured once while on march. He was taken prisoner three times, escaping twice. On the third time he was held as a prisoner of war at Petersburg, Libby Prison, Salisbury Stockade, and Danville, finally being exchanged in 1864.

Col. Schneider held nearly every position in the regiment during its term of service, from private to colonel, and was the last commander of the 2nd MI. He remained at this post until being mustered out with his regiment July 28, 1865.

Following the war, Schneider married Elizabeth Strengson, a German-born immigrant, in August 1865, and they had five children with only one son and one daughter surviving to adulthood. He worked as the chief of the Abstract Department for the State of Michigan through December 1890 and then went into business for himself. The Schneider residence, which is now a historic building in Lansing, is featured in a draft letter and picture in this collection. Colonel Schneider died November 4, 1917 in Lansing and is buried at Mt. Hope Cemetery.

The 2nd MI Infantry was organized by Francis W. Kellogg at Fort Wayne, in Detroit, MI, in April 1861 and mustered into Federal service for a three-year enlistment on May 25, 1861.

The 2nd MI left for the front on June 5 and helped take up the defenses of Washington. It was engaged at Blackburn's ford, and covered the retreat from Bull Run three days later. From this point forward, the 2nd MI saw heavy fighting for the rest of the war. It fought in the Peninsula Campaign, Second Bull Run and Chantilly in the Eastern Theater. In June 1863, it joined Grant's army in Mississippi and participated in the siege of Vicksburg and the assault on Jackson, MS in July. The regiment rejoined the Army of the Potomac the following year and participated in the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna, Totopotomy, Bethesda Church, Cold Harbor, and the first assaults on Petersburg, Hatcher's Run. They were in the trenches before Petersburg during the winter and aided in its capture in April 1865. The 2nd MI participated in the Grand Review at Washington and was mustered out on July 28, 1865.

Schneider’s 1864 POW letters, the first from Libby Prison, dated Nov. 3, the second from Danville Prison, dated Nov. 23, were written to his parents from the prison camps and only contained minimal information, such as…I’m well and a prisoner of War…Prisoners of War do not write more than one page nor seal the envelope. Do not feel disturbed about me. Give my love to all at home. Given the terrible conditions of the prison camps and the miseries of the war in general, this could hardly have been of much comfort to worried parents. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB