Lieut. M.C. Foote, 44th New York Volunteers, POW, Civil War Correspondence, Including 1864 Diary with Hand-Drawn Escape Map of Winyah Bay, Plus

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 12, 2015 - Jun 13, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

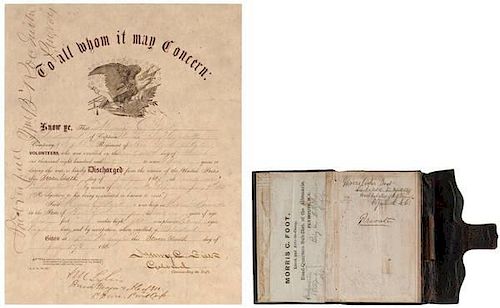

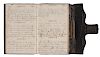

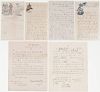

Lot of 30+ items, including Morris Cooper Foote's 1864 pocket diary, with 4 x 4.75 in. hand-drawn escape map of Winyah Bay (fully separated from diary); 26 war-date documents and letters; post-Civil War newspaper and postcard illustrating Libby Prison, Richmond, VA; and 2 Civil War-related books previously owned and identified to Foote, the first, Prison Life In The South: At Richmond, Macon, Savannah, Charleston, Columbia, Charlotte, Raleigh, Goldsborough, And Andersonville, During The Years 1864 and 1865, by A.O. Abbott, 1865, the second, Reports of the Committee on the Conduct of the War: Fort Pillow Massacre, Returned Prisoners. House Of Representatives 38th Congress, 1st Session. Report No. 65 and 67, 1864.

New York native, M.C. Foote originally enlisted in the famed Ellsworth Avengers’ regiment, the 44th New York Infantry. While with the 44th NY, he distinguished himself with meritorious service at Malvern Hill (July 1862), earning a promotion to second lieutenant. Shortly after, Foote transferred into the 92nd New York Infantry, and while serving with the 92nd, Foote was appointed aide de camp for his uncle, General Henry Wessells, who commanded the Department of North Carolina from late 1862 to the end of the war.

On April 17, 1864, the 92nd, which had a garrison of about 3000 men, was attacked at Plymouth, NC, by CSA Gen. Robert F. Hoke with approx. 15,000 Confederate troops and the ironclad Albemarle. Following a defense that lasted 3 days, Gen. Wessells surrendered the town, which resulted in the capture of approx. 1200 Union soldiers, including Foote. It is the battle and capture of Plymouth, NC, that serves as the backdrop for Foote’s 1864 diary offered here.

Between April and November 1864, Foote served in six Confederate prisons, including Libby and Danville Prisons in Virginia; Camp Oglethorpe in Macon, GA; at the City Jail and Roper’s Hospital in Charleston, SC; and finally in Camp Sorghum, SC. On April 26, Foote notes in his diary that he and the other captured men reached Richmond, stating, In the famous Libby at last – find things as bad as represented, living in hopes of an exchange. During his brief time at Libby Prison (12 days), Foote doesn’t mention any escapes, but on May 5, he does make note of hearing about an approaching battle between Grant and Lee, which is likely a reference to Grant’s Overland Campaign. He was transferred to Danville on May 7, and only spent 5 days at the prison that he described as worse than Libby. From May 14-July 28, Foote was at Camp Oglethorpe in Macon, GA, and he found the living conditions much more agreeable at this location. On July 4, he notes, Several speeches made this morng & patriotic songs sung around a small American flag that was smuggled in prison. The Rebs ordered the performances stopped. He also reports five escapes from the prison camp, including one on June 27, which involved the use of an elaborate tunnel system. Among the war-related news that reached the prison camp, Foote apparently heard of the possible sinking of the CSS Alabama on July 12, which turned out to be true. On July 19, a positive report was received that Sherman Cavalry are making a raid to Andersonville where our enlisted men are, but a day later, the false and disappointing rumor spread around the prison camp that Grant was dead!

Following his time in Macon, Foote was transferred to Charleston, SC, starting out at City Jail from July 29 – August 14, and moving to Roper’s Hospital, where he was confined from August 15 – October 5. On August 3, Foote articulated one of the greatest fears every POW had in crowded prison conditions, If we are not moved from here before long, some disease will break out. We are crowded up in filth. Yellow Fever outbreak was particularly worrisome to the prisoners as well as the city, and it was a concern related to Yellow Fever spreading that resulted in Foote being moved from Charleston and transferred to Columbia in late September.

Foote arrived at Camp Sorghum in Columbia by early October, and less than 2 months later, he and another officer managed to escape from the prison camp on November 29, 1864, spelling their way down the Santee River courtesy of the valued assistance of the contraband-negro population. The entries from the entire month of December are filled with tremendous details regarding Foote’s escape, which ended when he and his fellow officer were picked up on December 12 by the USS Nipsic in Winyah Bay. Foote’s personally drawn escape map of Winyah Bay has resided in his diary since 1864. A partial transcription of the diary accompanies the lot.

After mustering out of the 92nd NY in December 1864, Foote reenlisted in late March 1865 with the 121st New York Infantry, just in time to see action at Saylor’s (also Sailor’s) Creek, VA, in which he was promoted to 1st lieutenant for his meritorious service.

In addition to his 1864 diary, other highlights from the collection include 8 letters written by Foote to his mother during the Civil War, with references to camp life, Generals George McClellan and Winfield Scott, the Peninsula Campaign, and more, most dated 1861-1864, with the exception of one written in 1857 by a 14-year-old Foote; plus at least 12 war-dated documents, special orders, etc., among them a Muster-In Roll issued to Foote on August 23, 1862, for service in the 121st New York, a formal notification issued to Foote, indicating that he has been appointed a captain by brevet for his services at Saylor’s Creek stamped by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, 2 official discharges presented to Foote for his service in the 44th New York and the 65th New York, and much more.

Books include: ABBOTT, A.O. Prison Life In The South: At Richmond, Macon, Savannah, Charleston, Columbia, Charlotte, Raleigh, Goldsborough, And Andersonville, During The Years 1864 and 1865. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1865. Hardcover. Illustrated. First Edition. Duodecimo. Previously owned by Morris C. Foote with his name in the book and bookplate. Signed twice by him, dated from San Francisco 1867.

Reports of the Committee on the Conduct of the War: Fort Pillow Massacre, Returned Prisoners. House Of Representatives 38th Congress, 1st Session. Report No. 65 and 67. Washington D.C.: 1864. Hardcover. Illustrated. Octavo. Previously owned by Morris C. Foote with his name in book from Cooperstown, N.Y. dated 1866. Damp staining, foxing. Fair.

The Morris Cooper Foote Collection

Lots 140-152

Cowan’s is pleased to offer an important collection spanning 40 years of material—40 years of the life of the soldier Morris Cooper Foote, great grandson of Lewis Morris—a signer of the Declaration of Independence—and great nephew of novelist James Fenimore Cooper.

When the Civil War began, Foote joined the army at the age of 17 in his home state of New York, where he mustered into the 44th NY Volunteers, a group that came to be known as Ellsworth’s Avengers. After a promotion to 2nd Lieutenant and a transfer to the 92nd New York Volunteer Infantry, Foote was captured by the Confederate Army at the Battle of Plymouth in 1864 and was sent to Libby Prison. Eventually, Foote and many other POWs were sent to Charleston, S.C. where both Confederate and Federal forces attempted to use prisoners as human shields to discourage shelling—an incident now known as the “Immortal 600.” As one of the Federal officers placed under the fire of the northern batteries at Charleston, S.C., he was the only one wounded. From Charleston, Foote was transferred to Camp Sorghum in Columbia, South Carolina, where he escaped. He later published the story of his escape and loved to share it with family and friends. In the concluding stages of the war, he served as a staff officer at the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox.

After the Civil War, Foote entered the 9th U.S. Infantry on May 1866, and on March 7, 1867, received a promotion to the first lieutenancy. He served with his regiment in California, Alaska, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska. In Alaska, he commanded one of the two companies that received the territory from Russia in 1867. Foote also served in Native American campaigns and expeditions under Generals Miles and Crook, in Wyoming, New Mexico and Arizona. As part of Foote’s time in Wyoming, he took part in the exploration of The Black Hills a year before the events of Little Big Horn. He also conducted the first census of the Sioux Indians after the 1876 treaty as part of his duties as the commanding officer at the Spotted Tail Agency. After the discovery of gold in the Black Hills—an event that caused controversy between miners and Indians and eventually lead to tragedy—Foote attended a meeting of miners who, deciding to leave the area as requested after hearing a resolution from the President of the United States, went on to create Custer City (present day Custer), South Dakota, now considered to be the oldest town established by European Americans in the Black Hills. On January 26, 1883, Foote achieved the rank of captain of the 9th infantry. In September 1886, he witnessed the surrender of the Apache chief Geronimo to General Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona.

Following the end of the Indian Wars, Foote’s regiment participated in the Spanish-American War. Foote commanded a battalion at the battle of San Juan Hill. At the formal surrender of Santiago, the commanding officer General Shafter selected the 9th infantry to receive the surrender of the city and province where Foote commanded a company stationed in the plaza. In August 1898, Foote received promotion to the rank of Major and orders to Boston on recruiting service, being unable to rejoin his regiment at the time due to suffering from Cuban malarial fever.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the U.S. Army dispatched the 9th Infantry Regiment to China during the Boxer Rebellion and the China Relief Expedition, where Maj. Foote took part in the Battle of Tientsin.

After being appointed a Brigadier General on February 18, 1903, Foote retired the following day. Foote retired to Europe and resided in Geneva for two years. At the Hotel d’Angleterre, after recovering from double pneumonia and double pleurisy he passed away of heart failure on December 6, 1905.

As a soldier and an officer, Morris Cooper Foote experienced first-hand the moments that shaped our history and set the stage for the 20th century. This exceptional collection includes diaries, journals, letters, documents, books, photos, maps, prints, personal belongings, and more pertaining to his professional and personal life. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB