Letters Concerning Choctaw Removal and Lands, 1832

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

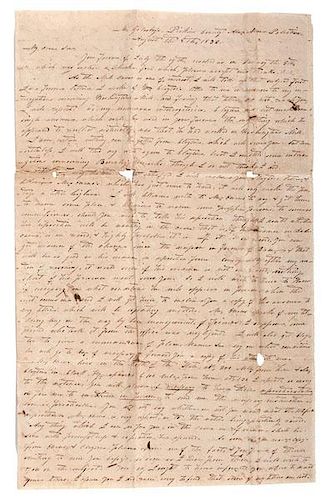

Letters Concerning Choctaw Removal and Lands, 1832

Lot of 2 extensive letters, William A. Harrison to Nathaniel H. Hooe, King George County, VA. One written at Mr. Galasbey's, Pickens County, Ala. Near Palestine / August the 8th, 1832. The other with no place or date. The first is 3+pp, on 10.25 x 16.25 in. The second, 4pp, 7.75 x 12.5 in. According to WorldCat, Hooe was Harrison's father-in-law.

The first letter concerns some court issues, with requests to have depositions taken. Harrison then turns to Choctaw Treaty and resettlement issues (much of his spelling retained): "I think Mr. Ellis takes more credit than is due him for reconciling the Choctaw disturbance which took place abt. the time I made my second trip into the Nation. which was in [M]ay. Oweing to the misconduct of a rascal by the name of Johnson who was a settler: a long headed speculator my the name of Grant who considered it to his interest to have as few whites in the Nation as possible, prevailed on Chief Missulatwiba (likely Moshulatubbee, chief of the southern division of Choctaw) to pe[ti]tion to Jackson to expell the whites, in pursuance with one of the articles of the Treaty: but Lafloar (likely Thomas LeFlore, who succeeded his cousin, Greenwood LeFlore, as chief of the eastern Choctaws), a chief of great influence & talent, considering it a trick, interfered, wrote [to] Jackson pretty much as follows: 'Sir, we invited the whites among us; we want them to remain, they buy our stock: but few of them are mischievous, & should we find it necessary to expell the disorderly, we will not trouble government to do it.' As for the prices given for Indian claims, they regularly exceed government price $1.25 per acre: for reserves the usual price is from 2 to $6 per acre: according to the quality of the land: And the common price for a float is from 5 to $6 per acre. I doubt whether the place where I first settled, which Cook & Ellis now claim under a float could be bought for $30 per acre."

He goes on to discuss issues of claims that cross section lines, and asks Hooe to find out the proprietors of the Democrat and Southern Advocate papers in Huntsville, telling him that he thinks the proprietor of the Democrat is named (Geo.) Woodson. It is unclear what he plans to put in these papers - ads as a lawyer? real estate negotiator? other?

He goes on to tell Hooe: "I shall stay most of my time in the [Choctaw] Nation. Where I first settled the water was so bad though very cool that I had to use river water: and at the other place the lake water in dry weather is so bad that I must try immediately near the lake & try to get well water: I think I can alter the taste, even if I can do no better than to dig a well so near as to draw it from the Lakes. I am not worse off than other persons who have settled on very rich land, except a few (very few) who have springs. In time water (well water) will be good & plenty. As I have mentioned before, the water & good land are not to be found together except rarely....The greater part of my claim is wood land opening into what is called Bald or open Prairie without extent almost: & much of the wood land is what is termed open woodland Prairie. On the wood land Prairie the grass is very high & on the open Prairie as high as a horses back in many places. Open Prairie is good corn land, & the wood land Prairie is good for any thing. The open Prairie fails in cotton after [a year] or [two or so] I am informed, Universally...."

He discusses the costs of various stock: $70 - 100 for a good mare, ponies or small mares sometimes as little as $20. Cows and calves $4 or 5. but "Where I have settled there are so many wild Hogs, that I fear all I buy will go wild."

The second letter is similar. Harrison discusses roads (impassible in winter, good in summer). "As to the Choctaw nation, I consider for the present, it would be dangerous for me to touch for there are now many claims, called floats, which the holders will not locate, waiting I believe to see a fine improvement to locate upon & as to those who are going over & making improvements, with a view to obtain a preem[p]tion right, they often disturb each other: one will find a Prairie, commence his House, & before he is done, another will come with a stronger force, & build & enclose so fast, that the first will be left so little of the desireable land, that he will go else wheres."

"I was only in the Nation 3 days, & was only in that part of the nation which lies in this state (presumably as noted on missing first page). The land generally is very poor, 10 acres of bad, to one of good: but some is as good as any in the world: but on good land the water is bad, that is if you can get any....Take this state altogether, it I expect, is the poorest in the union: abroad it stands well & many come here expecting to trade to advantage: but money is as scarce here as any where else: the market is well stocked with everything, & with many things overstocked. Large fortunes have been made here by farming, & still larger by merchandize....I was offered for the Wagon & gear $175, payable in June: but I will not sell it for any thing in reason: for during the year I have made conditional arrangements to employ it in moving the Indians, & that trip would be worth clear near $300." He discusses more about the cost of horses, the opportunities available, and more.

The birth of a state, with good and bad aspects. An important period, as the Choctaw removal was the first "Trail of Tears," and reportedly this event led to the first use of that nomenclature in the press. Excellent information about Choctaw land claims. Additional letters between the two men can be found at the University of Virginia Libraries, special collections.

The Choctaws (Chahtas) once had some 50 towns in what is now Mississippi and western Alabama. They were divided into three geographic groups - western, eastern, southern (Six Towns), each later elected a principal chief, but each town would have been politically independent. They are probably descendants of one (probably of many) of the mound-building groups that once occupied central Alabama to the Mississippi, indeed most of the eastern United States. After the American Revolution, trade with the new nation increased. By the turn of the 19th century, the people were farming, cultivating cotton, raising horses and livestock, operating inns and other businesses, selling various manufactures in the markets - in other words, assimilating to the Euro-American lifestyle (many even converted to Christianity). And yet, the various governments - federal, state, local - found reasons to "steal" the land - picking away at Choctaw territory year by year, often with the excuse that "Americans" could make better use of the land than "savages." Even where the "Civilized Tribes" had developed the land to European "standards." (Maybe especially where the land was developed, since the farms were then "move-in ready.") Some Choctaws had even supported Andrew Jackson in the war with the Creeks (1813-1814), but as President, Jackson still ordered their removal west of the Mississippi (usually "for their own good").

On paper the movement to Oklahoma (then "Indian Territory") appeared to be orderly. The people were given through most of October to harvest their crops, sell any real estate or goods they could not move, and gather at Memphis or Vicksburg by Nov. 1, 1831 for transport to a new Nation. Then it all went wrong.

There was inadequate transport and supplies. Mother Nature seemed to be opposed to the move - first weeks of rain, flooding the lower Mississippi and its tributaries; then came a blizzard and days of freezing temperatures. Riverboats burned or broke down; land along the river was a swamp, so that offloaded people had to walk miles in up to waist-deep water; rivers were choked with ice so wooden-hulled boats could not leave the dock.

The new Bureau of Indian Affairs offered a $10 bonus, ostensibly with guides and full support along the route, to any who would walk to the new lands, with expected results. The guides misrepresented their knowledge of the territory, and one group of 300 people was apparently lost in a flooded area. Supplies were inadequate even when they arrived at forts and other areas that were expecting immigrants. The Choctaw claim that about one-third of those who left Mississippi that first year died along the way, but the United States did not bother to keep any records of the losses, if, indeed, they even knew about them.

The second and third years were not much better than the first, although in 1833, nature was not on the rampage that it had been the first two years. There were individual "removal agents" who did care for groups under their care, stashing supplies along the route or avoiding areas with epidemics raging (such as the cholera outbreak in Vicksburg in 1832). Unfortunately, some of the agents did not get along and could not work together for the benefit of the people. But for the most part, it was still a difficult journey. One problem in all of these resettlement attempts, even as late as the Navajo "Trail of Tears" and settlement at Bosque Redondo (1860s) and the Sioux resettlement in the Dakotas (1870s and 1880s) is that the government consistently underestimated the number of people in the tribes. (The Army had estimated only 5000 Navajos lived in the southwest. But three times that number ended up at Fort Sumner, many died along the way, and still others managed to avoid capture.)

Eventually nearly 8000 people were transported to Indian Territory, and principle chiefs elected. People then began building their Nation in a new setting according to ancient principles and new forms learned from their American neighbors. By the turn of the twentieth century, Choctaw towns looked pretty much like other American towns with the typical variety of manufactures and services from tailors to billiard halls, banks and light industry.Letters folded and toned. Some ink burning through. A few holes along the folds, but only a few words impacted. First page missing from second letter as noted.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB