Leo Miller, Naturalist & Explorer Involved in Theodore Roosevelt's "River of Doubt" Expedition, Archive Featuring Correspondence from Roosevelt and hi

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 20, 2015 - Nov 21, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Leo Miller, Naturalist & Explorer Involved in Theodore Roosevelt's "River of Doubt" Expedition, Archive Featuring Correspondence from Roosevelt and his Sons

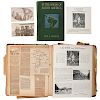

An archive of approximately 23 letters, some with envelopes; 6 books, 5 signed by the author; 3 photographs, including the original 5.25 x 3.25 in. silver gelatin print of identified members of the South American expedition, as well as an enlarged copy print; a scrapbook of newspaper clippings of Leo Miller's accomplishments; lecture broadsides; and a South American artifact from the collection of mammologist, Leo Miller.

Leo Miller was a member of the Theodore-Rondon expedition from 1913-1914. His notes documented over 450 specimens and 97 different species in several regions. The collection of mammals gathered on the expedition was the first, and practically only, mammal material the American Museum received from either Brazil or Paraguay at that time. In total the trip gathered 2,000 species of birds and 500 mammals. A digital collection of Leo Miller's notes are available on the American Museum of Natural History's digital repository. Several of the artifacts from the expedition are still on display in The Hall of South American Peoples at the American Museum in New York City.

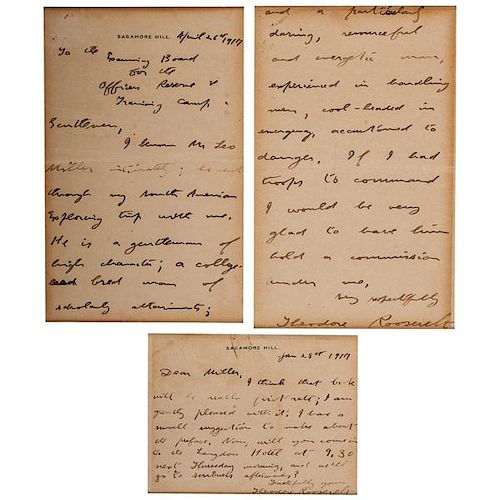

Six of Miller's letters are from Theodore Roosevelt, including two ALsS from January and April, 1917, and four TLsS dating from November 1914 through December 1917. Eleven letters are from his sons, Theodore Jr. (five TLsS, Jan. - May 1934) and Kermit Roosevelt (two ALsS, Feb. 1916 and Feb. 1917; four TLsS, July 1930 - May 1938). Theodore Roosevelt Sr.'s letters respond to Miller's expeditions and adventures and offer well wishes for Miller's book about their exploits in the Amazon.

In a November 3, 1915 TLS, Roosevelt writes to his dear Miller,

You must have had a most interesting trip. By George, those maribundi wasps are serious menaces to the health and life! When you are in the lowlands, do keep a lookout for the giant anaconda...[the American Museum of Natural History] have never yet gotten the skin or the skeleton of one...

In another TLS, dated November 4, 1914, Roosevelt wrote,

I have received your note too late to answer before you had left. I hope this will be sent to you. I shall be very much pleased to have the Saki named after me, and I am even more pleased to learn how many new things we got in the mammal collection. It is fine! And, I am sure, you will do even better now. I am also very much pleased that you think you will be able to publish your Tales in book form. Send me a copy of the Cock-a-della Rocky article, as soon as you can, and I will submit it to Scribner's. Give my warm regards to Messrs. Huxley and Gibbon. I cannot help but wish that I was along...

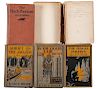

The "Tales," as Roosevelt called them, culminated into Miller's first nonfiction book, In the Wilds of South America (1918). His experiences produced several other fiction novels: The Hidden People (1920); In the Tiger's Lair (1921); The Black Phantom (1922); Adrift on the Amazon (1923); and The Jungle Pirates (1925), each published by Charles Scribner's Sons. All of the books are available in this lot, with the five fiction novels personally inscribed by Miller to family members.

The collection also includes correspondence from Paul R. Cutright written during his time as a member of the faculty at Beaver College, Jenkintown, PA (four TLsS,1943-1955; ALS, Jan. 1956). Dr. Cutright, who is best known for his extensive study of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which developed into a 506pp volume, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (1969), was writing to Miller in hopes of interviewing him about his experiences with Roosevelt. He was in the process of writing a book focusing on Roosevelt as a naturalist. In the ALS from Cutright, dated Jan. 1, 1956, he is actually writing to Miller's wife expressing his sadness after hearing the news of her husband's passing.

The Leo Miller Collection

Lots 219-223

Weary from politics and thirsty for danger, Theodore Roosevelt sought adventure to escape his failures of the 1912 election. After a safari in Africa he looked towards South America and a treacherous, unpredictable waterway aptly named the Rio da Duvida or River of Doubt. Death on the scientific crusade was a very real possibility. Many of Roosevelt's friends fretted over his safety. Laughing in the face of peril he replied, "I have already lived and enjoyed as much of life as any nine other men I know; I have had my full share, and if it necessary for me to leave my bones in South America, I am quite prepared to do so." His chortles silenced when the voyage shifted from a confident trek to a harrowing journey. In Candice Miller's book River of Doubt (2005) she explains, "Compared with the creatures of the Amazon, including the Indians whose territory they were invading, they were all – from the lowliest camarada to the former president of the United States – clumsy, conspicuous prey."

Roosevelt traveled with a large entourage of twenty-two men made up of scientists, explorers, camaradas (guides), his son, Kermit, and mammologist, Leo Miller (1887-1952). The American Museum chose Miller for the Roosevelt-Rodon exploration based on his expertise in tropical regions. His delineative notes documented over 450 specimens and 97 different species in several regions including western Matto Grosso, where Roosevelt reportedly wore the spur offered as Lot 221. The collection of mammals he accumulated was the first, and practically only, mammal material the American Museum received from either Brazil or Paraguay at that time. In total, the 900-mile, 40-day excursion gathered 2,000 species of birds and 500 mammals, but the scientific accomplishments came at a cost.

The men barely survived the journey. While traveling, Roosevelt severely gashed his leg. It became infected and almost killed him. In the middle of their route, a fever rendered him unconscious. When he woke, he said, “Boys, I realize some of us are not going to finish this journey. Cherrie, I want you and Kermit to go on. You can get out. I will stop here.” Kermit refused his father’s wishes and pushed on.

Roosevelt returned to the United States sixty pounds lighter, hobbling on a cane, and too weak to speak above a whisper. He did not “leave [his] bones” on the muddy banks of the Rio da Duvida, he did, however, sacrifice some of his life blood. “The Brazilian wilderness stole away 10 years of my life,” confessed Roosevelt. He never fully recovered from his leg injury and suffered almost constant malarial bouts until his death in 1919.

After the expedition, Miller continued to document and explore South America. In a letter included in Lot 220, Roosevelt expressed how very pleased he was that Miller planned to publish his “Tales” from their adventure in his first book, In the Wilds of South America (1918). His experiences inspired several other fictional stories set in the Brazilian wilderness. All of the books including In the Wilds of South America are offered in Lot 220; five are inscribed by Miller.The Roosevelt letters are in good condition but are mounted onto a 24 x 20 in. mat. A second set of Roosevelt letters are housed in a 15 x 18 in. frame. The pages are browned, but seem to be in good condition. They have not been observed outside of the frame.Condition

The scrap book has many fragile articles in rough condition with toning and severe tears. Almost all are glued into the book.

The photographs are in good condition the large silver gelatin of the group is from the original negatives from the photographer (confirmed by an enclosed letter) in its original 12 x 9.5 in. frame. A smaller, 5.5 x 3.5 in. silver gelatin, is included. It has several surface stains and marks. The third image is a real photo postcard of Miller and one of the camarades. It is in relatively good condition with one fold.

The books range in condition from fair to good. One cover is separated from the binding. There is some wear on the covers and the binding is lose. In the Wilds of South America, however, is in good condition. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB