Important Southern, Civil War Archive of the John Gresham Family, Incl. Letters to his Son, CSA Soldier Thomas Gresham, 2nd Georgia Battalion & Engine

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Important Southern, Civil War Archive of the John Gresham Family, Incl. Letters to his Son, CSA Soldier Thomas Gresham, 2nd Georgia Battalion & Engineer Corps

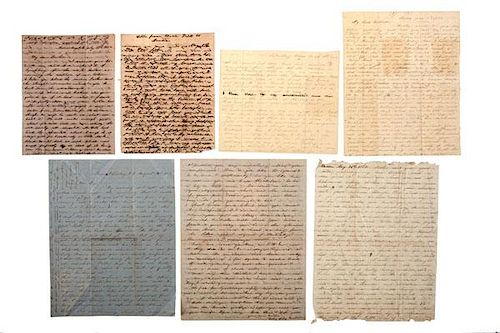

Lot of 50 Civil War-era letters from the Gresham family of Macon, GA to Thomas B. Gresham, 2nd GA Battalion Inf. and the Engineer Corps. Ca 1862-1892. Topics include slaves and plantation ownership, the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, the Siege of Atlanta, Stoneman's Raid, conscription of slaves, Camp Oglethorpe prison, and more.

The patriarch of the Gresham family, John Jones Gresham, was born in Burke County, Georgia, January 21, 1812. He was the son of Job and Mary Jones Gresham and attended school at Waynesboro, Richmond Bath, and University of Georgia. He privately studied law and was admitted to the Georgia bar in 1834. He opened a practice in Waynesboro but moved to Macon in 1836. He married Mary Baxter, one of Thomas W. Baxter and Mary Wiley Baxter’s eight children, on May 25, 1843. They had three children together: Thomas B., Leroy, and Mary “Minnie.” Two other children died in infancy. In the 1840s, Gresham quit his law practice and devoted more attention to his plantation, Houston, located south of Macon. Eight of his slaves resided at his home on College Street in Macon, his remaining forty-three slaves lived at Houston. He was elected mayor of Macon in 1843 and 1847. In 1850, he established the Macon Manufacturing Company and served as its president. Four years before the Civil War, he became a judge, and, in 1865, he was elected to the Georgia State Senate. His prestige and power in the Macon community did not mean his children lived an easy, carefree life or secure his assets during the war.

Illness constantly plagued his son, Leroy. His agonies only multiplied when a tall chimney, a remnant of a hotel fire, collapsed and broke his left leg when he was nine years old. He never fully recovered from the injury and developed a severe abscess on his back. He weighed only 63 pounds when he was sixteen years of age. According to his diaries held at the Library of Congress, he recorded his oscillating states of health, noting not only the symptoms accompanying his infirmities, but also the remedies: morphine, Dover's Powders, belladonna plasters, and brandy. He absorbed Confederate sympathies from his involved family and community, and, with the energy of a young boy, he fervently wrote about events on the battlefield, the railroad, and rumors whispered at home. In one of his 20 letters to his brother, Leroy wrote, We have just had a visit from Mr. Dayne. His Battalion (the 27th) has just come here to guard the Yankee officers... A Yankee Capt was shot the other night by one of Findlays Batt for cursing him when he ordered him off the line and since then the prisoners have been docile enough (Macon, May 28, 1864). The prison Leroy referenced was Camp Oglethorpe which housed more than 2,300 Union officers in the summer of 1864. Conditions at the camp were similar to most Civil War prisons. Food was scarce, sanitation lacked, and dysentery and scurvy rampaged through the makeshift jail. A friend of Leroy, CSA soldier, Nathan Sayre, confided that, he would rather go to the front than stay [at Oglethorpe] and guard these Yankee prisoners any longer (June 10, 1864). By late July 1864, Union cavalry raids forced the prisoners to move, although some officers stayed until September.

Thomas B. and his uncle, Capt. Richard Baxter, shared similar discontent and woes of war as Sayre, but to a greater degree. Thomas B. served in the 2nd GA Battalion Inf. until 1863. He endured gruesome fighting at the Seven Days Battles, 2nd Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga. He transferred to the Engineering Corps in 1864, but pleaded with his father to transfer him to another regiment closer to the front. LeRoy often responded to his older brother's pleas with encouraging messages assuring him that their father would request his transfer. Their father was unable to influence his relocation because Thomas’ superior officer wrote that his services were could not be spared (August 10, 1864). Leroy wrote to Thomas,

If you were here your individual services could not aid us any and then you could not be with us at all, for you would be sent to the trenches in Hood’s Army. Father and Mother hope that you will make yourself contented and they feel thankful that you are out of this danger and that fear for your safety is no added to their other anxieties (Sept 7, 1864).

Thomas’ uncle, Capt. Richard Baxter, 3rd GA Re. Co. K and 15th GA Reg., also experienced horrific combat. He wrote to his nephew Thomas,

I have seen men who an hour before were happy and joyous stricken down by the ball of a yankee hireling. I have seen Yankees shot down so close to us that we could hear the death rattle in their throats. I have seen men die in every possible position and with all kinds of expressions upon their faces…I have had the balls and shell flying all around me but thank God none have hit me (Richmond, July 25, 1861).

Richard fought in more battles including the Battle of Seven Pines and Gettysburg. At the Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam), a ball finally hit its target, Richard’s hand. Union forces captured him at Dandridge, TN and interred him at Rock Island Military Prison. He responded to a letter from his sister, Mary, while in prison,

Your letter brought tears to my eyes. Don’t you think this an evidence of how It moved me for it is seldom such a thing happens. Its stern duties of a soldier leave but little time to indulge the greater emotions of the heart….I try to bear my imprisonment as [illegible] as possible. Naturally I look on the bright side [illegible] everything and my association with your Dear Edge has started(?) to improve me in that respect. He comes as near being a true philosopher as any man I ever saw…I truly hope it will not be long until ere I look into [our dear mother’s] face…(Rock Island, May 8, 1864).

Unfortunately, Baxter was not released from prison until the end of the war. Included in the lot are three more of his letters from prison and one more from the front.

Although he did not directly fight on the front lines, Johnathan Gresham contributed to the Confederate cause financially, serving in the home guard, and acting as chairman of the Macon Battlefield Committee. While chairman, Johnathan traveled to Kennesaw Mountain where General Johnston prepared for a grisly fight. Leroy wrote,

Our army occupies a fine position in front of Marietta and from the summit of Kennesaw mountain the scene is said to be indescribably grand—Both armies can be seen as if one grand panorama; every movement is plainly visible. It is said with how much truth no one knows, that is was “Old Joe’s” intention before he left Dalton to “make the fight” in the neighborhood of the Chattahoochee. The men are buoyant and confident and believe that all will yet go well. Never was there so bold a movement as Sherman’s and O if we do thrash him it will be indeed a thrashing! For Gen. Johston will never, never suffer the fragments of his army to cross the Etorah! (June 15, 1864).

Four days after Leroy’s letter, Johnston’s men worked through the night, digging trenches and creating fortifications, morphing Kennesaw into an intimidating earthen fortress. Leroy wrote,

[Father] saw the whole of Hoods Corps pass on its way to reinforce a threatened part of the line and says they could hardly be seen for the mud that covered them. Johnston has given up Kennesaw Mt and the next retrograde move will bring him to the side of the Chattahoochee (June 22, 1864).

Convinced that Johnston stretched his line too thin, General William T. Sherman initiated an unsuccessful frontal attack. Sherman said it was, "the hardest fight of the campaign up to that date." He lost the battle and approximately 3,000 men, including generals Charles Harker and Daniel McCook.

Although he heartily supported the Confederate Army, Johnathan’s view of the war was much more pessimistic than his optimistic son, Leroy. John wrote to Thomas, The news from Richmond is very encouraging but the situation in our front is not satisfactory. I have very little hope that Atlanta can be held…If Atlanta falls the state will be thoroughly perforated by cavalry and we shall lose all out property whenever they strike (August 14, 1864).

John had a right to fear losing his property. Human capital (slaves) in Georgia began retaliating. Leroy wrote to Thomas after Stoneman’s Raid, Generally speaking, not near so many negroes ran away to join [the Yankees] and they did not force them off. Some two or three independent darkies were “paroled” for declaring their freedom by our men (August 10, 1864). A few weeks later, an owner woke to her young slave acting suspiciously,

Little Bob is in jail—Mrs. Hill woke up at night and found him at her bedside with his hand on her. What the little rascal’s intentions was is not positively known though you can readily conjecture. I don’t think he will swing for it, though it is not improbable. Father says he does not look on negroes as he used to and took it quietly when he heard it (August 31, 1864).

Beyond slaves acts of defiance, the Confederacy began conscripting slaves. Minnie wrote to Thomas,

The government has begun to impress the town negroes. Its agents have been very busy for the last few days. They say that they want them only for a short time to work on the fortifications at Atlanta. The other day Loy and father were riding in the carriage when a man with a musket ran after them calling to them to stop and threatening to shoot Howard, but father told Howard not to stop and so he was not impressed as the man evidently intended he should be. (Minnie, June 25, 1864)

The world John once knew changed dramatically during the war. He neither felt safe nor secure. Mary wrote to Thomas again,

Macon is no longer the quiet home it was when you left. Wagons and horses are continually passing and the soldiers often disturb the slumbers of the other members of the family with their shouts (as you very well know). I very seldom hear them. (August 3, 1863)

Choked with wounded soldiers, many of Macon’s buildings, including the Women’s College transformed into military hospitals. Mother visits [the great many sick and wounded] sometimes now and has “got acquainted” with some of the men and so feels very much interested, wrote Minnie.

The sights and sounds of war so close to his doorstep made John feel little hope for victory and fear for his property. Battle-hardened soldiers like Benjamin C. Smith disdained men like John. Smith served with Thomas in the 2nd GA Batt. Inf. Unlike Thomas, Smith continued to serve in the regiment and fight at the Battle of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Petersburg. Thomas presumably wrote to his former regiment mate about his father’s misgivings and inquired about news from the front in Virginia. Smith ruefully responded,

All VA is full of peace rumors and while we hope something might turn/term(?) up, we are determined to fight to the bitter end, rather than submit, and it is with feeling of grief and shame mingled with scorn and indignation that we notice the conduct of some men in Georgia, for we consider it rather hard that while the soldiers who have borne all the hardships, and peril of war, and are still willing to bear them, and doing all they can to gain our liberty men at home, who have grown rich by speculation whose God is their money, and who have no higher or holier feeling than to clothe their back, and feed their stomach, should act so as to cause the blush of shame to mantle the check of every true Georgian who he hears her spoken of contemptuously by other states, and who like whipped spaniels, and ready to crawl to the feet and lick the hand of their (not ours) yankee masters, crying “Peccarri(?),” and begging that their property may be spared my only wish is, that these men, may have to endure some of the true horrors of war, in this war is continued, that they may lose their ill gathered gain, and that the tongue may wither, and the hand falsy(?) of the first man, who advocates a dishonorable peace. Tell your father that: it is in compunction with such men, as he is, that this army hopes to save the country from ruin. (Petersburg, February 3, 1865)

Smith had the chance to fight until the bitter end at Appomattox, where General Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865.

Soon after the war, on June 18, 1865, Leroy finally succumbed to one of his many illnesses. He died at the age of sixteen. John briefly formed a legal partnership with his son Thomas, but he soon retired to manage his financial interests. He died in 1891 while visiting Minnie in Baltimore. Eight of his Civil war letters; a book, Memorial of John James Gresham; a copy of a letter concerning his death; and a news clipping of his obituary are in the lot.

Thomas Gresham married Tallulah "Lula" Billups, the daughter of Hon. Joel A. Billups, on October 15, 1869. She died of tuberculosis in 1879. They had one son, Leroy, a Presbyterian minister. Twelve documents relating to him are offered in this lot. In 1887, he moved his practice to Baltimore. That same year, he married Bessie E. Johnston, an active member of Baltimore chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy who amassed a notable collection of Confederate manuscripts and relics. He died in Roanoke, Virginia in 1933.

Minnie graduated from Wesleyan Female College in Macon in 1865. She married a prominent Baltimore lawyer, Arthur W. Machen. They had three sons. Their middle son, John Gresham Machen, became a well-known Presbyterian theologian. Four post-Civil War items and 7 of her letters are in the lot. She died in 1931.

For a detailed look at the contents of the archive, go to: http://www.historybroker.com/collection/gresham/index.htm.

Bessie E. Johnston Gresham Collection of Confederate Manuscripts, Photographs, & Relics

Lots 89-115

Bessie E. Johnston Gresham was born in Baltimore, MD in 1848 in a home sympathetic to the Southern cause. Union forces imprisoned one of her brothers for aiding the South, and her brother Elliott was a Confederate officer who lost a leg at the battle of Antietam. She became an ardent and unreconstructed Confederate, and, in 1887, she married Thomas Baxter Gresham, a Confederate veteran from Macon, GA. She was actively involved in the Baltimore chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and amassed a notable collection of Confederate manuscripts, photographs, and relics at the Gresham home at 815 Park Avenue in Baltimore. Most of her items were left to the Museum of the Confederacy, the Maryland Historical Society, and other institutions. This important collection of Johnston-Gresham family and Confederate-related material, was passed down through Bessie Johnston Gresham’s step-son, Leroy Gresham, before it was acquired by the consignor.

The collection features over 50 CDVs accumulated by Bessie and Thomas Gresham, offered as Lots 89-100. Some are wardate, and others were apparently acquired in Baltimore soon after the war's end. Some CDVs include patriotic inscriptions and quotations written by Bessie on reverse, which showcase her deep feeling of love and devotion to the Southern Cause.

In a June 1862 letter delivered through the Union blockade, Elliott Johnston, serving as aide-de-camp to CSA General Richard B. Garnett, mentioned collecting photos of CSA generals for his then 14-year-old sister Bessie.

In a 1926 issue of Confederate Veteran magazine, a memorial essay described Bessie's girlhood during the war:

"One of her brothers, who was on General Ewell’s staff, suffered the loss of a leg at the battle of Sharpsburg; her two other brothers were active Southern sympathizers and were under constant surveillance by Federal authorities for giving all possible aid to the Confederacy; her home was a center from which radiated help."

"Reared in this atmosphere of deep love for our ‘cause,’ she became an ardent and unreconstructed Confederate."

During her girlhood, Bessie was acquainted with many Southern generals and received from them letters, photographs, and autographs, as well as a number of gifts.Very good some toning of the paper and scattered foxing on a few of the pages.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB