Important Revolutionary War Naval Document, Official Record of the Court Martial of Captain Whipple, Signed by John Paul Jones and Other Naval and Mar

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 21, 2014 - Nov 22, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

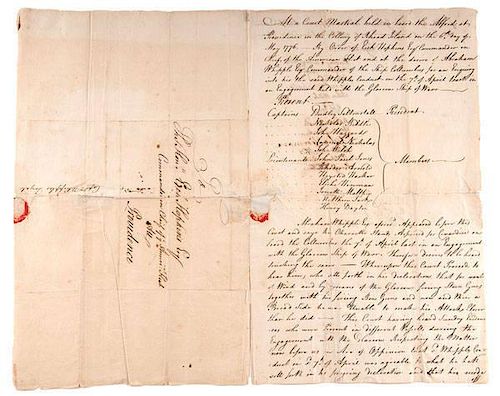

Important Revolutionary War Naval Document, Official Record of the Court Martial of Captain Whipple, Signed by John Paul Jones and Other Naval and Marine Corps Officers

2pp, 9.2 x 15 in. Folded with integral leaf sealed with wax. Thought to have been the copy retained by Esek Hopkins as the Commander in Chief of the Navy, as the leaf was addressed to him at Providence.

From the earliest days of the emerging nation, the founders and military leaders argued the merits of a permanent (and significantly large) navy, in large part because of the expenses involved – sea power does not come cheaply. Because of the time required to build ships, outfit them and train their crews, there were few American fighting ships at the start of the Revolution. The Continental Congress also saw the futility of challenging Britain’s rule of the waves – she had hundreds of vessels and trained crews. What the colonists wanted most from France was the support of her navy, which was both already established and in closer proximity to Britain. Congress envisioned the role of whatever navy was assembled, including privateers, as being one of harassing British shipping and interrupting the flow of supplies to His Majesty’s forces in North America, rather than building ships of the line. And because of this merchant target, it became an attractive opportunity for the more daring of the captains of existing ships to outfit their vessels as privateers, since the cargo and vessel (if still seaworthy) could make a fortune for her owner and crew, a sort of legal piracy.

The harassment of shipping – even extending to British home waters – let the “mother country” know her rebellious colonies were flexing their growing muscles. It wasn’t until October of 1775 that the Congress, after much difficult debate, decided to establish a navy, though it was limited in scope. As the war progressed, more founders, such as John Adams, became convinced that the new nation, if it survived this conflict, needed a strong navy. Although others did not see it that way, and the infant nation sold off her naval assets a few years after the end of the Revolution, John Adams fought to rebuild the navy during his Presidency. He was responsible for building the USS Constitution and was the creator of the position of Secretary of the Navy.

The authorization given by the Continental Congress at the end of 1775 (the Navy recognizes October 13 as its “birthday”) was for the purchase and arming of two merchantmen, which became the Andrew Doria and Cabot. Others followed: the Alfred, the Columbus, the Providence, the Wasp, and the Hornet. In December, Esek Hopkins (Cabot) was named commander in chief of the Navy, and Dudley Saltonstall (Alfred) and John Burroughs Hopkins, Esek’s son, were given (politically motivated) appointments. Fortunately, Abraham Whipple (Columbus), Nicholas Biddle (Andrew Doria) and John Paul Jones (1st Lieut. Alfred, and shortly after, Capt. of Providence) actually had experience in maritime warfare. Perhaps unfortunately, only the last has had any lasting recognition in the public arena; many of the others made contributions as well.

In February 1776 the first tiny fleet was ready for its maiden cruise. Led by Commodore Esek Hopkins, it set out for the Bahamas to raid British stores there, although orders were to sail to Virginia and the Carolinas. According to the report filed by Commodore Hopkins to John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress: “…I…formed an expedition against New Providence which I put into Execution the 3rd March by Landing two hundred Marines under the Command of Captn [Samuel] Nicholas, and 50 Sailors under the Command of Lieutt [Thomas] Weaver, of the Cabot who was well acquainted there – The same day the took Possession of a small Fort of Seventeen Pieces Cannon without any Opposition safe five Guns which were fired at them without doing any damage – …I then caused a Manifesto to be published the Purport of which was (that the inhabitants and their Property should be save if they did not oppose me in taking possession of the Fort and Kings Sores) which had the desired effect for the Inhabitants left the Fort almost alone – Captn Nicholas sent by my Orders to the Governor for the keys of the Fort which was delivered and the Troops march’d directly in where we found the several Warlike Stores agreeable to the Inventory inclosed,…”

However, the inexperienced Navy was not on alert through the evening before – their approach had been noted. Hopkins goes on to say: “…but the Governor sent 150 barrels Powder off in a Small Sloop the night before….” The primary objective – gun powder – was gone. (Clark, 1969, vol. 4: 735)

Samuel Nicholas, on board the Alfred, commanding a company of Marines, filed a similar report on the actions at Fort Nassau. He goes on: “On the 4th instant, we made the east end of Long-Island, and discovered the Columbus (who had parted with us the night before) to windward… We made Block-Island in the afternoon….At twelve o’clock went to bed, and at half past one was awakened by the cry of ‘all hands to quarters.’ ….We soon discovered a large ship standing directly for us. The Cabot was foremost of the fleet, our ship close after, not more than 100 yards behind, but to windward withal. When the brigantine came close up, she was hailed by the ship, which we then learned was the Glasgow man-of-war; …” He goes on to describe the battle – the Cabot was damaged and had to retreat, which then left the Alfred free to fire, as she would have hit the Cabot had she fired earlier. He describes the death of his Second Lieutenant and damage to the Alfred. “The battle continued till daylight, at which time the Glasgow made all the sail she could crowd, and stood in for Newport; our rigging was so much hurt that we could not make sail in time to come up with her again. At sunrise, the Commodore made the signal to give over the chase, he not thinking it prudent to risk our prizes near the land [a couple had been captured before the engagement; the only prize in the battle was Glasgow’s tender], lest the whole fleet should come out of the harbor. The Glasgow continued firing signal guns the whole day after.” (1969: 749-751)

The Americans lost 10 killed and 14 wounded, while the British only lost one killed and three wounded. However, all British casualties were the result of musket fire, not cannon fire. The Glasgow, a sixth-rate ship, carried 20 nine-pound guns. Only the Alfred and Columbus had nine-pounders – the Alfred, 20, and Columbus, 18. The others were only armed with four- and six-pound cannon, and the Providence also carried swivel guns.

While cruising the waters around Block Island, in the search for more prizes, Commodore Hopkins divided his fleet into two columns: the eastern one consisting of the Cabot, followed by the Alfred, and the western was headed by the Andrew Doria followed by the Columbus. The Providence, Fly and Wasp were escorting the prizes they had already captured, and thus slower than the larger vessels. The US fleet had suffered illness from its days of formation, before it left for the Bahamas. Various fevers and smallpox ravaged the crews. As the mission continued, the need to crew the prizes further reduced the manpower on the fighting ships. Because the fleet was divided and scattered, some of the ships, especially Columbus, were late to the engagement with the Glasgow.

As the days went on, however, accusations of cowardice began to follow Captain Whipple, until Whipple demanded a court martial so the evidence to clear his name would be made public. This document records the conclusion of that inquiry.

At a Court Martial held onboard the Alfred at Providence in the Colony of Rhode Island on the 6th day of May 1776 – By Order of Esek Hopkins, Esqr Commander in Chief of the American Fleet, and at the desire of Abraham Whipple Esqr Commander of the Ship Columbus for an Enquiry into his the said Whipple’s Conduct on the 7th of April last in an Engagement with the Glascow Ship of War – [followed by list of those present at the Enquiry]

…Abraham Whipple Esqr aforesaid appeared before this court and says his character stands Aspersed for cowardice onboard the Columbus the 7th of April last in an Engagement with the Glasgow Ship of Warr, therefore desires to be heard touching the Same – Whereupon the Court proceeds to hear him who setts forth in his declaration that for want of Wind and by means of the Glasgow firing stern guns together with his firing Bow guns and now and then a broadside he was unable to make his Attack closer than he did This court having heard sundry Evidences who were present in different vessels during the Engagement with the Glasgow respecting the matter now before us are of Oppinion – That said Whipple’s conduct on said 7th April was agreeable to what he hath sett forth in the foregoing declaration and that his mode of attack on the Glasgow in our Oppinion has proceeded from Error in Judgment and not from Cowardice – [signed again by the same 12 men who were listed as present] (and 1969, vol. 4, 1419-1421)

The men who acquitted Whipple of cowardice include:

1) Dudley Saltonstall. He was second in command to Hopkins, and commanding the Alfred during the battle.

2) Nicholas Biddle. Biddle was one of the first four Navy captains. He perished during the war in 1778 when the magazine in the ship Randolph, of which he was in command at the time, exploded. Biddle also appears to have been the most vocal critic of the actions in the Battle of Block Island.

3) John Hazard. Hazard was in command of the Providence in this action. He was convicted of cowardice and dismissed from the Navy.

4) Samuel Nicholas. First captain, later Major, of the Marine Corps. He was the only one to hold this rank during the Revolution, thus becoming first de-facto Commandant of the Marine Corps.

5) John Welch. A junior officer, likely part of the court as a witness.

6) John Paul Jones. 1st Lieut. on the Alfred, and second in command during the engagement. He is often considered the “Father of the US Navy” as the most recognized naval hero of the Revolution.

7) Rhodes Arnold. Another junior officer, also likely a witness.

8) Hoysteed Hacker. Commander of the Schooner Fly, which stood down during the battle, being loaded with ordnance.

9) Elisha Hinman. Probably a junior officer at this point. Commanded the Alfred at a later date.

10) Jonathon Mattbie. Another junior officer, probably a witness.

11) Matthew Parke. Marine captain on the Alfred.

12) Henry Dayton. Junior officer, probably a witness.

A significant document of the earliest encounters of the Continental Navy.

In addition to Hazard being convicted of cowardice and losing his commission, this episode was a “black mark” on the record of Esek Hopkins, in large part because he attacked Nassau without orders to do so. Within two years, other accusations, such as inappropriate distribution of goods taken without the permission of Congress, led to his dismissal from the Navy, also.

Abraham Whipple went on to serve throughout the entire War, commanding a variety of vessels, and even commanding a small squadron by 1779. He took dozens of prizes, including one of the richest of the war. At the end of hostilities, he took up farming in Rhode Island. He became associated with the Ohio Company in 1788, and was a pioneer into Ohio, helping to open the Northwest Territories and becoming one of the founders of Marietta, where he died and was buried in 1819.

Reference:

Clark, William Bell

1969 Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Washington (DC), Vol. 4.Condition

Folds and light toning as expected. Slight scuffing. Still very readable.

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB