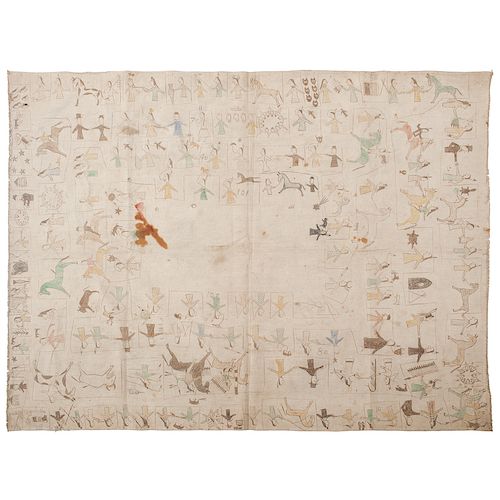

High Dog (Lakota, 19th/20th century) Winter Count on Muslin

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 5, 2019

A large auction of over 450 lots, featuring the Southwest Collection of Harriet and Seymour Koenig, NY. Highlights of the sale also include a Dance Stick by Joseph No Two Horns (Lakota, 1852-1942), Winter Count by High Dog (Lakota, 19th/ 20th century), a Tsimshian Carved Staff, and much more. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

painted in green, yellow, red, blue, black, and brown; with pictographic depictions of historical events of the Sioux from 1798 through the early 20th century, 34 x 46.5 in.

early 20th century

This example is similar to a winter count collected and interpreted by Aaron Beede. Beede (1859-1934), an Episcopalian missionary, purchased a winter count from High Dog in 1912. After interviews and translations, he created a written key in both Lakota and English explaining the pictographs. This key is held within the collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota (http://history.nd.gov/textbook/beedeInterpretationHighDogCount.pdf).

Indians of the Plains used the winter count to record the sequence of years in calendrical form by correlating each year with an outstanding event. Annually, the tribal council an official recorder determined upon the happening that would be used to designate that "winter". A glyph, representing the occurrence, was then placed in proper sequence upon a tanned hide. In later years, cloth was substituted for leather. Regular review and explanation of all notations kept the memory of them intact in the minds of the recorder and of the tribal council. It also served to impress the tribal history upon the retentive faculties of the younger generation...

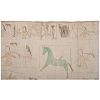

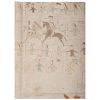

As is typical of Plains art, the drawing in this count is crude, in flat planes and profiles only. There is no attempt toward perspective, inclusion of backgrounds, or shading of colors. The figures illustrated are primarily the human and the horse, though a beaver (1800), scalps (1816), a tepee (1818), comets and stars (1821, 1833, 1909), corn (1823), snowshoes (1827, 1841), mountain lions (1845), a blanket (1847) are also used, to name a few. Whites are differentiated from Indians by the diagnostic feature of a hat. Crows, and other enemies, are usually shown with a characteristic top-knot (1812). Diseases like smallpox are illustrated by marking the human figure with dots (1810, 1837); wounds are made obvious by splotches of red in the appropriate places (1815, 1829). Each figure or glyph is outlined in what appears to be brown ink. While some representations are partially or completely filled in with the same medium, others are colored with read or green crayon (?). Individuals, Dakotas or whites, can be identified by their personal glyph attached to them by a line. Little Beaver (1811), for example, is accompanied by the outline of the animal after which he is named; Hawk (1817), Sitting Bull (1876), and Crow King (1884) are each recognized by an appropriate representation of his namesake (Praus 1962: 1-2)

Praus, Alexis. The Sioux, 1798-1922: A Dakota Winter Count. Cranbrook Institute of Science, 1962 (44). - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB