Henry J. Dallaher, Connecticut 1st Heavy Artillery, Civil War Archive Featuring Correspondence and Pencil Sketches of Camp Life

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 20, 2015 - Nov 21, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Henry J. Dallaher, Connecticut 1st Heavy Artillery, Civil War Archive Featuring Correspondence and Pencil Sketches of Camp Life

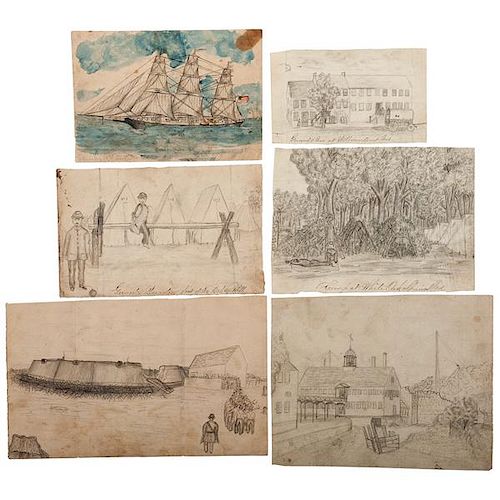

Lot of 80, including approx. 72 letters and 6 sketches, ca. 1861-1883.

When imagining soldiers' lives in one of the bloodiest incursions in American history, many envision its soldiers constantly dodging bullets and mortar shells. Very few realize that men spent a small portion of time on the battlefield. The majority of their days were at camp. Gripped by boredom, soldiers sought amusing diversions by playing music, gambling, participating in sports, or drinking. Henry J. Dallaher spent his leisure time writing long letters home and sketching. His collection of 72 letters, 7 on patriotic letterhead, and 6 drawings offered in the lot paint an interesting picture of camp life, desertion, and insubordination in the Civil War. Henry J. Dallaher enlisted as a private in 1st CT Heavy Art. Co. E. Many of the men in his regiment enthusiastically answered President Abraham Lincoln's initial call to enlist, making it the first state regiment ready for field of service and the first three year regiment to travel through many cities. The swift enlistment of the 1 CT Heav. Art., however, did not mean the regiment was comprised of valiant fighters. Many were naive boys with aggrandized visions of war. When they discovered battle was more horrific than they ever imagined, many attempted to desert.

When Dallaher and his regiment left Hartford for Chambersburg, he described on June 21, 1861 that the dust was so thick [he] could not see the man before [him]. They marched on for three miles in the hot summer sun and had to stand one hour in the middle of the street without the least bit of shade but the sitisens of Hartford ware very kind to us. Thay had washtubs of lemonade on most every corner but for all that the streets was lined with men falling out of the ranks being so exhausted thay could not walk. Admiring crowds waved the company towards the river boats. As they floated down current, cheers continued from the banks. The men disembarked the ship and returned to the road. Dallaher described the reception as grand all the way along. It took 25 cars to bring us through and two engines in some places people brought cakes, lemonade, and sometimes wine to the cars and offered warm loaves of bread and butter. It was the fantastic send off every soldier wished for as they departed for the "glorious" battlefield, hoping to return soon as champions.

After the dust settled, Dallaher and his men set up camp. Slaves come in our camp to sell cakes, small be[?], segars, strawberries and cream, milk and bread and in fact every thing to eat. Skeptical officers advised their men not to eat the food for feer of being poisend. Doubtful of his officers reservations, Dallaher reported, nowone has been poisend yet...

The weapons in the men's hands were more dangerous than the slaves' food. Inexperienced soldiers sometimes misfired their weapons which resulted in accidental deaths or injuries. On the march towards Chambersburg, Dallaher's regiment experienced a casualty when a careless soldier's weapon discharged. The soldier cleaning his gun was not able to reassemble it before drill. He grabbed a rifle of his tent mate who, while sleeping on guard, neglected to dead the charge but had taken of the cap ...the order was given to fire the lock struck fire and the piece exploded. the ball going through one side of a tente and through a napsack three inches bellow a mans head that was lying asleep with his head on it. and out of the other side of the tent and through a mans leg that was seting on another tent reading. shatering the bone so that it will have to be taken off at the knee.

Some men “accidently” shot themselves to avoid combat or, in the case of one man in Dallaher's regiment, while attempting to escape. On August 21, 1861 Dallaher describes a deserter [who] fell out of the ranks and attempted to get into one of the bagage wagons. Before he could flee, his musket went off and the ball past through the lower part of his body and lodge in his thigh. He survived the injury only to be placed in front of a firing squad on top of his coffin. He sat still a minute and then roled over on his side on the ground, writes Dallaher, when the doctors went up to him and found he was onley wounded so the men war ordered to fire again. Desertion was a serious offense, however, officers hesitated to sentence deserters to death. Fewer than 200 executions were ordered by commanding officers in the Union and Confederate armies, making Dallaher's experience especially rare.

Another man attempting to shirk his duties told Dallaher’s sister and others at home inflated tales of his time at war. He was sent home when we served at Fortress Monroe after leaving Fort Richardson, reveals Dallaher, he was sick and has never as much as smell powder and is he doesn’t return to the Peninsular in double quick time he will wake up one morning in jail and be sent to the Ripsaps[?] as a diserter… (July 23, 1861) Even one of his commanding officers overstayed his furlough, as soon as he returned he was arrested and relieved of duty. Dallaher admitted that no punishment was as heartbreaking to witness as the court martial of Duffe of Co. K for treason. Dallaher explains:

Duffe was ordered to be branded with the letter D on the left hip and have his head shaved and be drummed out of camp at dress parade... [He] was not drummed out of camp until the 16th on account of bad wether. The regt was drawn up in line at 9 A.M. and Duffe made his appearence with his head shaved as smooth as glass. accompanyed by six guards, two in front with sum revised bayonets fired, two behind on a charged bayonet and one on each side with arms apart so that the bayonets were all within a foot of his breast and a drum and pipe playing the roges[?] march the morning was one of the couldest we have had there was two inches of snow on the ground and it had rained and frose…it was one of the hardest things I have seen yet (January 17, 1862).

Disciplining regiments was an enormous challenge to Union commanders, because many of the men were volunteers who were unaccustomed to the authoritarian procedures. Officers penalized rebellious soldiers for cowardice and desertion by branding, like Duffe. Dallaher sketches another humiliating and painful punishment for unruly soldiers named “riding the wooden mule.” Dallaher pencils a defiant foot soldier with his hands bound behind his back. He sits on a makeshift beam in the center of camp made from chopped timbers while his feet dangle above the ground. Officers administered this punishment for a few hours or an entire day. He scrawls at the bottom, Guards Quarters fool of the Ft. Rich Hill. On August 24, 1862 an entire company disobeyed their commander. Dallaher writes:

Lt. Col. came out with a revolver and commended [Co. K] to march to their quarters, and thay would not obay him. He sayed thay must obay him and they first man that showed the last sign of insubordination he would shot him dead…Co K would not move and Lut Col toled the Capt of Co B to make them prisoners and take them to Genearl Banks and thay aloud themselves to be bound…thare muskets taken away from them, and ware marched 10 miles to the Gens headquarters. Punishing regiments and men established authority and deterred others from not following orders.

At his sister’s request, Dallaher sketched her views of camp, but drawing was very important to him. When his captain ordered the men to take only what they could carry from camp he left behind a blanket and kept his beloved drawing book. He was only able to draw in ideal situations, because working in inclement weather ruined his drawings. In this archive, Dallaher's illustrations include a penciled drawing of a line of soldiers entering the imposing Fort Richardson in VA; several men standing guard in front of three colonial buildings at Willamsport, MD while a covered wagon branded with the US insignia waits on the road; an unidentified building next to a crumbling brick wall with peaking ship masts; a wooded camp scene with brush covered tents at White Oak Spring, MD where one soldier rests his musket and back on a tree while another naps on the lawn, other men huddle together in tents possibly trading stories of home or discussing battle arrangements; and a penciled and watercolor sketch of a grand naval ship, the Great (?) Queen. The last drawing is not by Dahaller, but W.C. Pitt who either drew it in New York or is from that state.

Also included in the lot are six envelopes addressed to Dallaher's sister and Mrs. E. Dahaller, a pass for Dallaher to travel to Alexandria, VA on September 15, 1862, and two envelopes for forwarded paychecks by the Adams Express Company.Items range in condition but most are in very good condition with very legible writing. All of the letters have folds, only some have tears on them. There is minor soiling on a few.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB