General George Custer's Officer, James McLean Steele, 1868-1869 Diary Describing the Washita Campaign

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 22, 2018

Cowan’s American History: Premier Auction, scheduled for June 22, 2018 is comprised of early photographs, documents, manuscripts, broadsides, flags, and more dating from the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, Late Indian Wars, World War I and II and beyond. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Soldier’s diary, light brown in color, measuring 4.25 x 6.75 in., leather binding with cover flap. Faint writing on weathered cover reads James M. Steele/Adjutant 19th Kansas Cavalry. Entries include details of Steele’s service with the 19th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry under the command of Lt. Col. George Custer with references to the November 1868 Battle of Washita and descriptions of Custer’s 1869 pursuit of the Southern Plains Indians. Penciled entries on blue lined pages with red columns include 38pp of diary entries related to the 1868-1869 winter campaign against the Indians and an additional approx. 16 pp of notes related to the 19th Kansas Cavalry.

Diary is accompanied by the personal military history of James M. Steele as documented in his ca 1906 souvenir book Personal Military and Civil History, as well as an In Memoriam program printed by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States/Commandery of the State of Kansas following Steele’s death in 1916.

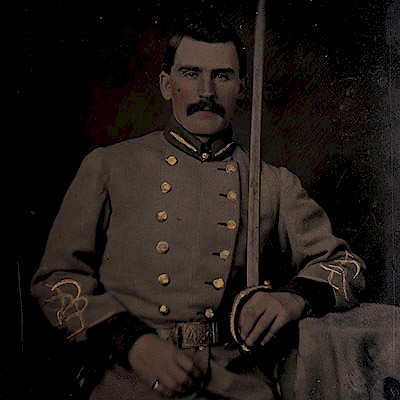

James McClean Steele (1839-1916) was born January 13, 1839, in Ross County, Ohio, one of eight children born to Colonel James Cooper Steele and his wife Elizabeth Findley McClean Steele. His father was politically active in Ohio, serving as a Free Soil Party candidate in the state and working to promote his abolitionist views as a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Following the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act which was to allow people in those territories to determine for themselves whether slavery would be allowed in their borders, Col. James Cooper Steele decided to move his family west to Kansas. In 1855 at the age of sixteen, James McClean Steele moved to Iowa with his parents and then ultimately in 1857 settled in Kansas. It was there that his military career began.

President Lincoln’s July 1862 call for 300,000 troops precipitated Steele’s enlistment in August 1862 for three years’ service with the Union Army. He mustered into service at Paola, Kansas, on 26 September 1862, as Captain of Company “E”, 12th regiment Kansas Volunteer Infantry. He was discharged for promotion on January 16, 1864, and simultaneously commissioned Lt. Col. of the 11th United States Colored troops (which was later consolidated with the 112th and 113th USCT to form the new 113th USCT). While Lt. Col. of the 11th USCT Steele was stationed at Ft. Smith, Arkansas, and engaged in limited combat operations, most notably surprising Confederate Col. Robert Newton’s cavalry at Boggs’s Mills capturing horses, arms, supplies, and Newton’s papers. Lt. Col. Steele mustered out of service on April 9, 1866, was honorably discharged, and returned to Kansas.

On October 20, 1868, Steele was commissioned 1st Lt. and Adjutant of the 19th Cavalry Kansas State Militia, at Topeka, Kansas. The 19th was formed after Kansas Governor Samuel J. Crawford offered state volunteers to Maj. Gen. Philp H. Sheridan, U. S. Army Department of the Missouri, to aid Sheridan’s efforts to quell Indian raids and violence in Kansas. The summer of 1868 in Kansas was a bloody and frightening one for frontier settlers, as renegade bands of Plains Indians attacked settlements in the region. The deaths of an estimated 100+ white settlers and assaults on white women, coupled with the fact that two Kansas women – Mrs. Anna Brewster Morgan and Miss Sarah White – were known to have been taken captive by Indians, incited a fury which hastened young men to heed the government’s call for volunteers. Governor Crawford recruited a mounted unit of volunteers from the state militia which was designated the 19th Kansas Cavalry, then resigned his governorship and assumed command of the newly formed cavalry. James M. Steele was one of more than 1200 volunteers who, eager to fight the Indians, joined the 19th Kansas for a six-month term of service.

The military’s plan to reign in the Southern Plains Indians was devised by Maj. General Sheridan and his commander, the famed William Tecumseh Sherman, who in 1868 was serving as Lt. Gen. of the Military Division of the Missouri. Sheridan and Sherman determined to wage winter warfare against their adversaries, betting that their chances for success would be heightened by taking the fight to the Indians at a time when Indian warriors were located close to their winter quarters and when Indian horses would be weaker from limited food resources. The Generals determined to destroy everything that sustained the Indians – food, shelter, and horses. Fresh off a recent suspension from military duty, Lt. Col. George Custer was specifically recruited by Sheridan to help inflict the final punishing blows to the Plains Indians and bring an end to hostilities in the region. With Custer firmly in charge of the 7th Cavalry, Sheridan is said to have advised Custer to “destroy villages and ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and bring back all women and children.”

As the 7th Cavalry prepared to begin its expedition against the Southern Cheyenne and other Plains Indians, James M. Steele and the 19th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry were sent to reinforce them. On November 5, 1868, 10 of 12 companies of the 19th left Camp Crawford in Topeka, Kansas, to march to Camp Supply, a remote army outpost in Indian Territory where Custer was waiting for them. It is on this day that Steele’s diary begins, “Thursday Nov 5th / The 19th Kansas Cavalry Col. Crawford Cmndng. Myself Adjutant, 1225 strong, broke camp from Camp Crawford Topeka and started for a 6 months campaign against the hostile Indians of the plains. The point to which our march is now directed is about 250 or 300 miles southwest and fully 100 miles from any settlement. The Regiment is well mounted and all its appointments as nearly perfect as possible.”

Steele’s entries continue daily from November 6th through November 12th, during which time he remarks generally upon his location and weather conditions, and alludes at times to the increasing scarcity of rations for both soldiers and animals. “Sunday Nov. 8th / Raining considerable at Reveille and continued to rain most of the day. Train has great difficulty on reaching Camp. Less than half rations of hay – full grain forage. / Monday Nov 9th / The worst day I ever experienced. Northwest snow storm from morning till noon and cool until evening when the weather settled & pleasant…. Wednesday Nov. 11th / Made a good march and went into Camp on the Whitewater near Meads. Full hay forage but no grain. Most of the command are out of rations having drawn to the 10th.” On Thursday Nov. 12th Steele notes simply that the party reached Camp Beecher, a supply station established in June 1868. This is Steele’s last entry for 1868, possibly because his regiment was soon to discover that Camp Beecher did not have enough rations for their men and animals. Over the course of the next two weeks the 19th would experience a difficult ordeal as it struggled to survive in terrible weather conditions with limited rations and an unknown path to their ultimate destination, Camp Supply. The 19th Kansas would arrive at Camp Supply in late November, however, they were depleted, hungry, and required a week of recuperation before they could once again be actively employed in operations.

The 19th’s delay in arriving at Camp Supply had another unintended consequence. The Kansas regiment did not arrive in time to reinforce Custer before he departed on his initial pursuit of the hostile Indians in the region, and therefore the regiment did not participate in the most significant, and controversial, battle of the army’s winter campaign. The Battle of Washita River, fought on the morning of November 27, 1868, pitted Custer’s 7th Cavalry regiment against Chief Black Kettle’s band of Southern Cheyenne who were in winter quarters along the Washita River in present day Western Oklahoma. Though some Cheyenne warriors defied their elders and launched attacks on white settlers and soldiers, Black Kettle had long been known as a peacemaker. For this reason, and others, Custer’s decision to launch an attack on Black Kettle’s encampment has historically been controversial. Of the Battle of Washita, Steele would only be able to describe its aftermath: “Dec 7 Started on our Campaign with 7th US Cavry. Lt. Col. Custer Comdg … Dec 11 Reached Washita River and stopped over 1 day to visit the battlefield of Gen. Custer. Saw evidence of a hard engagement with the Indians. Finding bodies of Maj. Elliott and 16 men of the 7th who were killed in the fight also bodies of 1 white woman and child. Captives probably killed at time of fight.” Major Joel Elliott and his men, killed at the Battle of Washita, were to become a stain on the reputation of Custer, who it was said by some did not do enough to aid them in battle. The white woman and child referenced here are Mrs. Clara Blinn and her son Willie, captives taken by Indians during an attack on a wagon train heading to Kansas from Colorado Territory.

Steele’s diary entries resume on March 1, 1869, with a brief catalog of his recollections of events which occurred in December 1868 through February 1869. March 1st 1869 … I cannot help a feeling of regret, that the last event of the last 4 months which have been prolific in adventure beyond anything I ever experienced should have passed by and I neglected to make even passing notes. / And now, as I often have to do when employing in this line, I must indulge in a little retrospect…. From here he notes his arrival on December 18 [1868] at Fort Cobb, where he finds a large number of Indians and Gen. Hazen who seems to be on the peace side of the Indian question. He notes the abandonment of Fort Cobb in early January [1869] and the movement of the whole command to Medicine Bluff Creek. He recollects that on February 12 [1869] Col. Crawford, the former Governor of Kansas, resigned his post and that his departure was an occasion for the officers to show Crawford a mutual feeling of consideration existing between them. On February 25, 1869, Steele notes that he received orders from Custer to be in readiness to march on the 1st, and that “Gen Sheridan and most of his staff have gone to Camp Supply for the purpose of arranging for the supply of our Command for what I suppose will be a Campaign against the Cheyennes & etc now supposed to be on some branch of the Red River or the Staked Plains.” The diary ceases to be reflection at this point, and becomes a much more detailed, contemporary accounting of Custer’s next phase of operations. March 1st brings us to the present date being under orders to march we broke camp and struck tents … Steele then writes near daily entries from March 1 through March 19.

With Col. Crawford’s resignation, Lt. Col. Horace L. Moore assumed command of the 19th Kansas. Adjutant Steele joined Lt. Col. Moore, and hundreds of other men of the 19th, who volunteered to go with Custer towards Texas in search of Cheyenne. The diary entries made over the course of the next few weeks describe the final push of the winter campaign, in which the cavalry faced harsh conditions, long marches, lack of food, and discord in the ranks. “March 5 Marched at 6 o’clock as usual and made about 20 miles. Our route a great part of the way was through Mesquite Plains, a character of [?] lands peculiar to this part of the world. …Yesterday they [the 19th] outmarched the Cavalry but today we fell behind, the men being pretty thoroughly exhausted. Camped on south or rather west bank of the north fork of the Red River having crossed it 3 times within half a mile…. Gen Custer has determined to divide the Command sending the surplus stores and poorest men to meet Gen. Sheridan….He takes from the 7th 200 and from our Command 400 of the best men and starts in the morning to hunt the Cheyennes of whom it is facetiously remarked he has lost a large number.”

With each day that passed the men grew increasingly tired, but evidence of previous Indian encampments on their route encouraged them that they were on the right path. Despite the hardships, Steele continued to relish the adventure of it all. He writes on March 7th that he “rode in the advance by Gen. C’s permission this afternoon and as he always goes with the Scouts I found following the trail quite exciting….” The scouts found a fresh fire the next day and a trail leading to a small group of Indians. There was a little excitement in the morning on the 8th, as a group of cavalry began pursuit. “…Scouts brought report that the Indians whose trail we were following had gone into camp about 2 miles above. As they had but a small party it was supposed the cavalry could manage them, so we stayed back a few of us watching from the hills as the disposition of the troops was made for the attack. The attack itself could not be seen as they were soon hid by an intervening bluff, we saw the cavalry move at the gallop to the designated points and then charge into the valley beyond. We waited in breathless anticipation the result….” The author quickly reveals that “breathless anticipation” is but an exaggeration, as the party being pursued amounted to just two or three warriors and their families. Steele notes that many of his men ridiculed the expedition, saying it was but a search for a one-eyed squaw. Ultimately, no Indians were captured. Steele reflects that ”There is a great want of confidence in Gen. Custer on the part of many of our officers and also in the 7th and the feeling is strongly partaken of by the men….”

Conditions continued to decline over the course of the next few days as the hunt for the Cheyenne continued. There was little wood for fires, no grazing for animals, and attempts to dig wells for water were unsuccessful. Then on March 10th, “Wind changed last night to the north and by morning we were indulging in an Institution peculiar to this Country, A ‘Texas Norther.’/One who has never experienced these institutions can have no idea of their severity…. The report is that our supply of forage will not hold out very long and then I fear we will be dismounted in Earnest if we do not lose our transportation altogether. Rations for 5 days (1/2 rations of bread stuffs) were issued today. The men thought it pretty hard to make such hard marches on short rations but after dark we rec’d orders to make those issued for 5 days last until the 18th ….” By March 13, the circumstances are becoming even more desperate: “The men were considerably exhausted and the animals much worse…. We have no grain for our horses today and the mules have had none for 2 days past. The Cavalry are fast becoming dismounted and mules giving out every day. We have been considering the propriety of abandoning tents and such other Camp Equipage as can be spared in order that we may be able to get through without being obliged eventually to abandon everything….At Col. More’s request I called on Gen. Custer and asked such orders as would justify the destruction of our surplus property, which was granted and orders given to destroy all our canvas messboxes and surplus property generally.”

After two weeks scouring the wilderness for Cheyenne and in the midst of great physical difficulty, the men of the 7th and 19th were soon to meet the enemy. A large Indian encampment was found on the 14th and later in the day the Indians came bearing a white flag seeking an interview with Custer. Steele and his fellow soldiers eagerly anticipated the battle that would follow: “A party of Indians came riding up to the front and some fun would have been had but the General sent orders back not to fire on them… There were now some 25 or 30 warriors in the rear and flanks, and as far as we could tell were disposed to be friendly. We pushed on supposing that Gen. Custer was only waiting for our Regt to come up to open the attack on the village which learned was but a short distance a head. Pushing on about 3 o’clock we reached sight of their villages, and here was a sight surpassing anything I have ever seen. The village lay in a valley (a splendid place to have attacked them) their lodges close together numbering 260 and the camp full of ponies, warriors, squaws & papooses & some dogs…. Warriors were skirting about over the hills on every side on the watch for some hostile movement on our part. During all this time Gen. Custer and the small body of cavalry were nowhere to be seen. I did not doubt that the Gen. was only temporizing with them until we came up, and that the fight would soon open.” Steel goes on to describe the Indian braves in glowing terms and shares information that will drastically shape the nature of their engagement. “I understand they have in one of their villages 2 white women, taken captives on the Solomon [River] last August. One of them is Mrs. Morgan a young woman who had been married but a few weeks previous to her capture. A brother of hers named Brewster has been with the Scouts of the Command ever since and is following up this Indian chase with a degree of tenacity highly creditable.”

The women Steele references were none other than Mrs. Anna Brewster Morgan and Miss Sarah White, the women whose kidnappings had helped ignite the fury of Kansas frontiersmen. Their presence in the Indian encampments would seemingly play a significant role in Custer’s handling of the ongoing engagement with the Cheyenne, and would also factor prominently in Steele’s remaining diary entries. Over the course of the next few days, a drama played out whereby Custer negotiated for the release of the captives and the men of the 19th awaited their opportunity to attack. Continuing his lengthy description of events from March 14th, Steele writes, “About 4 oclock the Gen notified us to have our men ready to form at any moment as he had taken some of the Chiefs Prisoners and they might attack with a view to recapture them. Nothing of the kind however was attempted…Of course our present Equivocal position is the topic of general discussion, and generally showed impatience and dissatisfaction with Gen. Custer. He has not been very popular with our officers at any rate, but all have consoled themselves with the idea that Custer only wanted an opportunity and he would fight them….They marched [the men] about 25 miles today and could have cleared out the village in short order if the word had been to fight.”

On March 16th Steele writes that Gen. Custer is still handling the Indian situation without much show of fight, and he describes the unfolding negotiations. Custer is working to bring the Cheyenne in peacefully to the reservation with the other tribes and to secure the safe return of the female captives. The plan is for the captives to be turned over to the men of the 19th for transport back to their friends and families in Kansas. “Great sympathy is felt throughout the Command for these unfortunate women and it is given as one reason why the Gen. did not attack yesterday the fear that they would at once have killed their prisoners….” Despite promises to deliver the women on the 17th, the Indians do not follow through and tensions begin to mount. “March 17 … Of course this delay and the uncertainty of the result of these negotiations make our situation very unsatisfactory. Gen. Sheridan’s Camp is supposed to be about 35 or 40 miles north but Gen. C does not propose to communicate with him until he settles these matters or finds that he cannot accomplish his plans. In the meantime our supplies are running very low. They have issued what rations they have on hand and they must last to the 22d.”

Custer’s patience with negotiations was running thin when on March 18th he issued an ultimatum to the Indians which was recorded by Steele, “March 18 – …[Custer] told them they had lied etc & if They did not bring the Captives in by sundown tomorrow he would hang every prisoner he could get hold of, and sent them off in short order. We all went to bed with anxious hearts, as many considered they were playing false and those unfortunate creatures who have been for so many long months enduring a captivity worse than death. It is to be hoped the Gen. will be successful….” The next day Steele described the end of the standoff, “… about 1 o’clock Indians were reported on the hills south …. Our glasses would not tell us certainly whether they were the party we wished to see or not, but an orderly soon came from Gen. Custer requesting the presence of the Field officers of our Regiment & we then knew our hopes were to be realized. Gen Custer very considerately sent the Field officers of the Regt out to receive them and from a little hill in our Camp we watched the reception with Joyful hearts….” Steele continued with his description of the return, later describing the women, “Mrs. Morgan is a young woman, had been married but a few weeks and was captured in Oct. Miss White is single and is probably 18 years of age. They show excellent health and are I suppose about as happy as they can well be tonight.” Seemingly, the tide of dissatisfaction with Custer had turned as well. “Gen. Custers praise is in Every body’s mouth and men & officers who were before full of complaint with him as a Commander now declare they could stay 10 days longer and live on mule meat if necessary. Orders tonight are to start at 6 o’clock tomorrow for Gen. Sheridan.”

Here ends Adjutant General Steele’s dated journal entries. The remaining pages of the diary are predominantly blank with the exception of brief notes and several lists which appear at the end of the diary. Notes relate to supplies purchased and associated costs, while lists reference soldiers of the 19th with titles such as “Roster of Lieutenants for Herd duty” and “Guard Roster 19th Kansas Cavalry Vols.”

The 19th Kansas would march back to Camp Supply and then back to Fort Hays, Kansas, where Steele was honorably discharged on April 18, 1869. Following his discharge from the army, Steele remained in Kansas. In 1874 he married Miss Harriet “Hattie” McBean of Cadiz, Ohio, and settled in in Emporia, Kansas. They had no children. He was employed in the banking business for several decades. James M. Steele died January 27, 1916, in Emporia.

Overall, the diary itself is in good condition with writing that is clear and legible. On some pages there are small soil spots which do not affect the readability of the content. The tri-fold cover is worn, with one of the spines torn approximately half off from main cover. The most visible alteration to the original condition of the diary is that there are approximately 25 instances where a later owner used a blue pen to underline portions of the diary. The underlined are typically just a word or two though there are instances where a longer phrase is underlined. The majority of words underlined reference Custer.

James McClean Steele’s diary is a remarkable and significant addition to the body of literature related to General George Armstrong Custer, and is a particularly enlightening portrait of Custer’s 1868-1869 winter campaign. His diary sheds light upon some of the major issues surrounding Custer’s controversial role as an Indian fighter – deepening divisions in the 7th Cavalry, the brash nature of Custer’s leadership style, and the sometimes-questionable use of the U.S. Army to quell Native American resistance.

Details of Steele’s military career are cataloged in a souvenir book titled, Personal Military and Civil History which is included with his diary. An enclosed voucher No. 61977 indicates that the personal history book was provided to the Soldiers and Sailors by Historical and Benevolent Society, Washington, D.C.

James McClean Steele’s In Memoriam program, printed following his death in 1916 by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States/Commandery of the State of Kansas, accompanies the diary and military career souvenir book.

The consignor relates that the diary was purchased from a collector in a very small Western town, who had begun collecting in the 1960s. The previous owner, who had owned the diary for about 50 years, said he acquired it from one of Steele’s descendants.

Eliminate the Hassle of Third-Party Shippers: Let Cowan's Ship Directly To You!Condition

If you'd like a shipping estimate before the auction, contact Cowan's in-house shipping department at shipping@cowans.com or 513.871.1670 x219. - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB