Fort Laramie Treaty Witness and Civil War Veteran Captain Isaac d'Isay, 14th Ohio Infantry, 18th and 27th US Infantries, Extensive Archive Including I

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Fort Laramie Treaty Witness and Civil War Veteran Captain Isaac d'Isay, 14th Ohio Infantry, 18th and 27th US Infantries, Extensive Archive Including Indian Wars and Family Correspondence, 1865-1935

Lot of 800+ letters and documents related to Captain Isaac d’Isay and his family. Ca 1865-1935.

Before Isaac d’Isay was thirty years old he immigrated to the United States, fought in one of the most gruesome battles in American history, suffered in some of the most notorious Civil War prisons, and experienced the West. In his private diary he wrote, I feel happy in the thought that my life thus far has not been in vain… (February 4, 1869) The comprehensive archive goes into great detail not only of d’Isay’s historic experiences but also into his personal life, matters of the heart, and the lives of his immediate family.

Items in the lot include: approximately 75 intense love letters from d'Isay to his wife written during his time serving in the Indian Wars; 3 detailed letters and journal entries of his witnessing the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty; 2 daily journals from 1868 and 1869; approximately 5 letters from Reconstructionist Texas; letters concerning his real estate ventures in Kansas City, Fort Wayne, Cincinnati, and other locations; deeply personal letters to his young children; other family correspondence from siblings and parents; hundreds of letters from d'Isay and his wife, Alida, to their only surviving daughter, Laura, who married into the Lippincott Glass Company family; d'Isay’s typed account of his experiences as a Confederate prisoner and his daring escape attempts; documents concerning his appeal before Congress to be placed on the retirement list and receive a pension for his military service; letters from personal friends and famous soldiers such as O.O. Howard, Henry Blanchard Freeman, and Henry Haymond; family photographs and CDVs; 17 of Alida’s journals from 1868 to 1873, 1919 to 1929, and 1931 to 1935; newspaper clippings of his and his wife’s obituaries; and more. The entire archive encompasses his life from 1868 until 1925 and the legacy of love he left behind through his wife and daughter until 1935.

Isaac d’Isay was born in Breda, Netherlands in 1839 to his father, Joseph and mother, Lydia. After losing almost all of his land in the Netherlands, Joseph moved his family to the United States in 1848. They settled in Washington Township, Indiana or Washington, Ohio and owned one of the more successful farms in the area. Despite his father's marginal success, Isaac did not become a farmer. Instead, he worked as a clerk and a druggist until he enlisted in the army.

Isaac d'Isay (at the age of 22) joined the army with his brother Egidius (aged 18) and enlisted as a private on April 22, 1861. He mustered into the 14th OH Inf. Co. A. After his first three month tour, he reenlisted into 18th US Inf. Co. A. in February 1862. He received a series of promotions until he reached the rank of sergeant-major in 1863. Under General Don Carlos Buell and General Rosecrans in the Army of the Cumberland, d'Isay participated in gruesome fighting at the Battle of Stone River, Hoover’s Gap, and Chickamauga where he was captured. In prison, his superiors recommended him for another promotion to second lieutenant of the 18th US Inf. for his valiant efforts at Stone River and Chickamauga. He accepted the promotion in November 1863 only to be promoted again two months later to first lieutenant.

He was a POW at Richmond, Danville, Andersonville, Savannah, and Millen. In a partial letter to his sister, Charlotte (Lottie), he explained that his devotion to God and supportive letters from his family helped him survive the darkest and gloomiest days of [his] life while a prisoner. (Camp Bato, Lookout Mountain, TN, July 25, 1865). Later in life, he typed an account of his capture at the Battle of Chickamauga and his life as a prisoner. He described exchanging counterfeit Confederate notes to enemy soldiers for additional food, epidemics of small pox and dysentery at Danville, and a spring of pure water [that] miraculously burst through the earth in [their] prison quarters [at Andersonville] (Fort Wayne, IN September 20, 1909). He also wrote about his three escape attempts.

In his most successful effort, d'Isay managed to steal the coat of one of the Confederate officers and casually jump over Danville prison's fence. He and several other men managed to make it to a swamp where they stole a canoe. Physically exhausted, he accidentally fell asleep guiding the boat down river. It hit a snag and capsized, tossing the men into the murky waters. An African American man found them the next morning, clinging to floating logs. The man tried to direct them out of the swamp, but he was too weak to continue. The man put d'Isay on the back of his mule and took him back to the prison hospital. While being treated for dysentery and exhaustion, a Confederate doctor asked d'Isay to help him compile a list of sick Union prisoners to exchange. He agreed to help the doctor for additional food. Instead of offering food, the doctor proposed to put his name on the list. The favor resulted in his freedom. He was finally traded for a group of sick and wounded Confederate prisoners in November 1864. He continued his military service reaching the rank of captain of the 27th US Inf. in March of 1867, just before he headed West to fight in the Indian Wars.

After the war, the army stationed d'Isay in Fort Wayne, IN. There, he dabbled in real estate and began a courtship with a young seventeen-year-old girl named Alida Morss. Alida was a member of the pioneering Fort Wayne Morss family. She was born on September 18, 1850 to Susan and Samuel S. Morss. Samuel was a clerk by profession but held several important positions in Fort Wayne including mayor in 1859. Alida had three other siblings: Laura, Samuel E, and Susan. After their marriage, the d'Isays funded Laura’s education through seminary school. Samuel E. went on to become a very successful journalist. He became the editor of the Fort Wayne Sentinel and the Fort Wayne Gazette. He also worked as the editorial writer and the Washington correspondent for the Chicago Times. Early in his life, he expressed some interest in politics and authored two letters to his uncle, Nathaniel S. Berry, the governor of Massachusetts during the Civil War, but his role in politics did not come until 1888 when he acted as a representative for Indiana in the Democratic National Convention. President Cleveland rewarded Samuel’s loyalty to the party by appointing him Consul-General of the United States to France in April 1893. After serving four years in that position, he returned to Indiana and continued his work in news until his death in 1903. The two ALsS, several letters written by Samuel, and five (several from one of his trips through Europe) journals are offered in this lot. Also in this lot are several letters from Laura, her certificate of graduation, and one of her journals.

d'Isay first had the happiness of seeing Alida one morning in church. Taken aback by her dark hair and striking blue eyes, he strained to catch another glimpse of her but her form was entirely hid from [his] sight by the numerous forms between [them] (Fort Columbus, New York, March 17, 1867). He finally gathered enough courage to speak to her and ask for her hand in December 1866. Soon after their engagement, d'Isay was ordered to Fort Wood in New York. The distance was not easy, d'Isay requested from his friend and fellow officer, Captain Philister, that he be reassigned to a permanent station in the West…not a thousand miles from [his] last station, but the request was not granted (Metropolitan Hotel, New York, March 13, 1867). He continued to serve his post as battalion quartermaster and post adjunct in New York. On route to several brief trips to Chicago, New Orleans, and Omaha, he spent a few days with his sweet heart and dreamed about their long anticipated wedding day.

The d'Isays married at First Presbyterian Church on the corner of Berry and Clinton St. in Allen, IN on October 17, 1867. It was the outstanding social event of the year, with several wedding attendants and many wedding guests (The Fort-Wayne Journal Gazette, October 20, 1925). d'Isay chose Alida’s white silk wedding dress and trunk in New York purchasing them right before he left for the wedding (Fort Wood, New York, October 1, 1867). Several of their wedding cards are included in the lot.

The couple enjoyed a brief honeymoon to the Missouri plains and Nebraska which was a mix of business and pleasure. While out West, he and his company were some of the forces detailed to protect railroad builders working on the Union Pacific Railroad. After the honeymoon was over, Alida went back Fort Wayne while d'Isay returned to his post in New York. Later that year, he was assigned to Indian Territory to help establish several forts.

Days after his arrival in Dakota Territory he traveled to Fort Laramie for the treaty. He wrote to his wife from Fort Russel:

Nearly all the bands of Indians that are expected to treat have come in, so that a treaty of peace will not soon be made. The commissioners at present here are Generals [William S.] Harney, [Alfred H.] Terry, and [John G.] Sanborn. Generals Sherman and [O.O.] Augur are expected about the last of the month. I think there must be nearly two thousand Indians in and around the Fort. My room is next to the Council room where the commissioners meet so that which I write the Indians are forming and repassing and every few minutes peering into the room through the windows—an Indians polite manner of observation and taking notes (Fort Laremie, April 26, 1868).

It was an exciting time at the Fort and d'Isay understood its importance. The day of the Treaty he wrote:

A great many Indians numbering between three and four thousand having come in for the purpose of making peace, the commissioners decided to have a meeting with them yesterday and accordingly met them in a building properly fitted up with seats for their reception. The commissioners were seated on a platform built in one side of the building. There are only three present Generals Sanborn, Harney, and Terry, the other four, among whom is Genl’ Sherman, are expected in a few days. I went in about 11 o’clock yesterday taking a set on the platform among the officers of the Post, and found the building nearly filled with Indians. As soon as all the chiefs with their young warriors were in, Genl’ Sanborn opened the Council by making an address to them through an interpreter who seems to speak the Indian language quite fluently. He stated to them in substance that the Great Father at Washington had sent seven of them to make a treaty of peace with the Indians, that the three upper Forts should be abandoned in case they would make peace but that if they continued to make war, that more Forts would be built and a large army sent to fight them. He said the Great Father wished to protect them so that they might live and not die or be all destroyed, that this was the last time efforts for peace would be made. That it would be made for their own benefit and that they should not think we wished to make peace because we are afraid, for if they should kill off one army, another could be sent in its place. When the commissioner was through, “Iron Shell” a chief of the Brules Siouxs made a speech, in which he said substantially the following: that “he was glad to meet the white for the purpose of making peace, but he wanted the Forts given up so that they could have that country all to themselves and have their game come back which had nearly all been driven away by transit(?) to and from the Forts. He said in white man’s property without paying for it the white man had no right to go into their country without their consent. They had to depend on game for a living and were not brought up to till the soil”

Some others spoke in the same term and when they were through talking, the commissioners told them that they would meet again in the morning for the purpose of signing the treaty. So this morning they met again…A few short speeches were made by the Indians but when it was told them that the treaty was ready for their signatures, after it had been read to them, they seemed to hesitate. Iron Shell said that treaties so often had been made and broken that he feared this one would also be broken. Finally after the commissioners had assured and re-assured them that they were big chiefs and the treaty would never be broken by the whites, they came up to sign, “Red Leaf” who is said to have led the fight at Phil Kearney, being the first to touch the pen. “Iron Shell” made quite a speech before he signed in which he again argued that the Forts be given up as soon as possible Genl’ Harney told him in reply that post as soon as the troops and stores could be withdrawn, they should be abandoned. On this promise quite a number came up and signed apparently in good faith shaking hands with the commissioners before they touched the pen But each one before he did so, said he signed with the understanding that the Forts are to be removed as a condition of peace. You can imagine how glad I felt when they went up to sign for I felt assured that the Forts would be given up as the commissioners now stand committed to their promise by the treaty.

The two principle chief “Red Cloud” and “Man Afraid of his Horses” have not yet came in but are daily expected, they will no doubt also sign the treaty, and then the commissioners will go up to the Missouri river to Fort Rice to treat with the Indians who are going there to make a treaty.

After the council adjourned all the Indians that had attended went to a “big feast” prepared by the squaws which consisted of boiled beef and hominy, coffee and light bread. They seemed to relish it very much. The commissioners and several officers of the Post including [me], went to see them feast. Tomorrow they will receive their presents (Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory, April 29, 1868).

The Fort Laramie Treaty ended the war along the Bozeman Trail with Chief Red Cloud. In the terms of the treaty, the United States agreed to abandon its forts along the Bozeman Trail and gave enormous parts of the Wyoming, Montana and Dakota Territories, and the Black Hills. One article ensured the “civilization” of the Lakota by providing "English education" at a "mission building.” White teachers, blacksmiths, a farmer, a miller, a carpenter, an engineer and a government agent resided within the reservation and established the Carlisle Indian Industrial School hoping that it would “protect the freedoms” of the Sioux. Chief Iron Shell’s fears were confirmed, however, when the United States broke the treaty after the discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1877. The US government seized back the land in the Black Hills and offered no reparations to the American Indians.

Days after the signing of the treaty, d'Isay traveled to Fort Fetterman and wrote to his wife:

When at Laramie Lt. Fenton arrived from Fort C.F. Smith he very kindly let me have his horse to ride back to C.F. Smith which belongs to the quartermaster there. I was very fortunate in having him, as Genl’ Sherman refused to let me have an ambulance [illegible] that he had none to spare. He seem quite unpopular among the officers and men of his regiment. Without the horse I should have had to ride in the wagon with the men.

He then moved on to Fort Phil Kearny where he received orders again to abandon the post. He wrote, a train of two hundred wagons are actually under way to this Post to move the stores, all of which is unmistakable evidence that this country is soon to be abandoned… (Fort Phillip Kearny, May 23, 1868)

Isaac d'Isay enjoyed his time out West and marveled at the beautiful scenery. He sent pressed flowers to Lida and told her about an exciting buffalo hunt in which he, Major Bust, Lieutenant McCarthy, and several American Indians participated. He wrote to Lida,

as soon as the buffalos descended the party they started on a run for dear life, and the party after them one of them after several shots had been fired with him (of which several wounded him) succeeded in making his escape from the hunters by crossing the river…after being chased some time in the neighborhood he was first seen he came directly towards the post by this time a great many shots had been fired at him and the excitement was at its height everybody turning out to see the ground chase…they finally succeeded in chasing him…we had buffalo steaks for dinner and breakfast… (Fort C.F. Smith, June 8, 1868).

Captain d'Isay had more interactions with Crow Indians at train stations and even within the Fort. He received a buffalo hide from one American Indian who, in return, ate in the mess hall. Two other Crow Indians were a small part of his regiment, but he rarely experienced any Indian fighting. He applied for a discharge twice in 1870, his superiors denied his first request. He filed again but immediately regretted his decision and asked that the request be ignored. Instead, it was granted.

As a civilian, d'Isay continued in his real estate business. He helped the commercial development of Fort Wayne and dealt in land in Kansas City, MO during one of the most exciting times in its development. Even though he primarily dealt in these cities, he conducted business all over the United States.

He and Alida had two additional children, Woodward and Alice, but neither survived to adulthood. Woodward died at the age of two in Minnesota of dysentery. Alice struggled with poor health her whole life. Hoping the dryer climate would improve her health, d'Isay and his wife, Alida moved their family from Fort Wayne to Kansas City when Alice was nine. She improved; however, she died three years later in 1899.

Isaac d'Isay briefly returned to military service in 1898 when the president restored his last position as captain. President McKinley appointed him to also be commissary of subsistence and chief quartermaster of the 7th Army Corps, 3rd Division. He was honorably discharged again on May 12, 1899. Before he was discharged, James Evans Lippincott proposed to his daughter Laura. He authored a letter congratulating him and noting that he hoped James would be a suitable husband for his precious daughter.

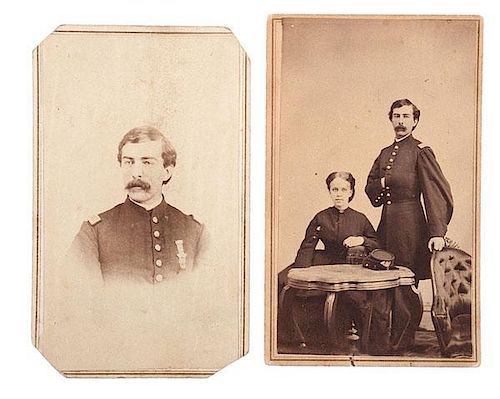

In the early 1900s, d'Isay appealed to the president and the courts that he should be granted a pension and able to claim retirement due to his discharge related to the over production of officers after the Civil War. His military friends and superiors including: O.O. Howard, Henry Blanchard Freeman, and Henry Haymond wrote letters in his defense or detailing his service. The courts granted d'Isay’s pension and retirement. The lot is comprised of all of the letters listed above, the court documents including the decision, and a TLS from President William Howard Taft while serving as Governor General of the Philippines. The collection also features 2 CDVS of d'Issay in uniform, one in which he is posed with his wife; a signed CDV of Brigadier General Henry B. Harrington in uniform; and a Civil War-era view of Lookout Mountain, TN, by R.M. Linn.

The d'Isays made Fort Wayne their home for 25 years until they relocated again to Cincinnati to live with their daughter, Laura. Twelve years after their move, Isaac d'Isay died in October 1925 due to complications from pneumonia. Several newspapers in Fort Wayne, Kansas City, and Cincinnati published long tributes about the war hero.

The rest of the archive primarily includes letters from Alida to their daughter, her journals, and other family related items.All of the letters are in very good condition with some toning of the paper and typical folds. Most letters retain their original, opened envelopes.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB