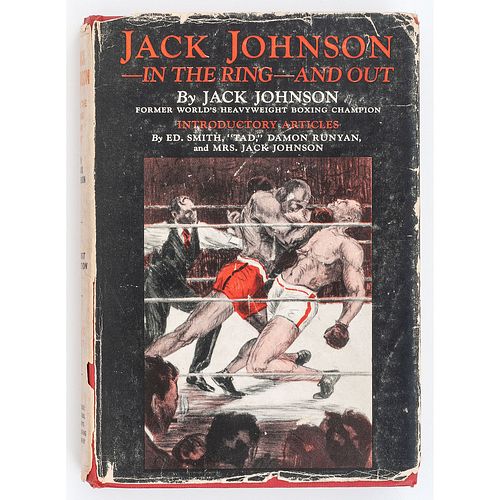

First Edition of Jack Johnson's Autobiography, 1927

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Dec 3, 2020

Cowan’s Auctions is pleased to be offering Part II of the Steve Turner Collection of African Americana. Comprised of over 240 lots, this remarkable collection tells the history of African Americans, especially their role in settling the western frontier in the 19th and early 20th century. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

JOHNSON, Jack (1878-1946). Jack Johnson - In the Ring - And Out. Chicago: National Sports Publishing Co., 1927.

8vo. Frontispiece and 14 additional plates. (Light evening toning, very occasional chip.) Original publisher's red cloth gilt (stain at joint); original publisher's illustrated dust jacket (chipping and creasing at edges, light soiling).

FIRST EDITION of Johnson's second memoir. Penned by the first African American Heavyweight boxing champion with articles by Ed. W. "Tad" Smith, writer Damon Ruyon, and Johnson's last wife, Irene Pineau.

The racist attitudes of early 20th century America are uncomfortably reflected in the remarkable career of boxing legend Jack Johnson. At the height of the Jim Crow era, Johnson became the first Black heavyweight champion. He was larger-than-life, dominating the ring and living an extravagant lifestyle, especially fond of racing cars and bespoke suits. His relationships with white women flaunted the racist taboos of the day. He was a man who lived life exactly as he wanted, but to many white Americans, Johnson’s unapologetic lifestyle while being Black, caused outrage and consternation.

Born in Galveston, Texas to former slaves, Johnson would recall growing up in a poor neighborhood where the racial segregation rampant across America did not seem to extend. He said, “As I grew up, the white boys were my friends and my pals. I ate with them, played with them and slept at their homes. Their mothers gave me cookies, and I ate at their tables. No one ever taught me that white men were superior to me.” He worked odd jobs before making his debut on November 1, 1898. He defeated his first white opponent, Jim Scanlon, on May 1, 1900, and claimed the unofficial “Negro Heavyweight Championship” title by February 1903 when he defeated “Denver” Ed Martin.

The reigning heavyweight champion from 1899 was Jim Jeffries, a boxer with tremendous strength and stamina but a man who refused to take fights with Black boxers, most notably Jack Johnson. By 1903 the Los Angeles Times called on Jeffries, “Jack Johnson is now the logical opponent for Champion Jeffries… the color line gag does not go now. Johnson has met all comers in his class, has defeated each and every one. Now he stands ready to box for the world’s championship … When they meet the world will see a battle before which the gladiatorial combats of ancient Rome pale into childish insignificance. And meet they some day will. It is up to Jeffries to say when. Johnson confronted Jeffries in a San Francisco saloon in 1904, but Jeffries never relented, announcing his retirement in 1905 stating that there were “no more logical challengers,” a claim that felt hollow even to the racist commentators of the day. Instead of meeting Johnson in the ring, Jeffries would stage a “fight to the finish” on July 3, 1905, between Marvin Hart and former light heavyweight champion Jack Root for one of them to become the new heavyweight champion. Hart won but would go on to lose to Canadian Tommy Burns on February 23, 1906.

Johnson would hound Burns for a fight for over two years, purchasing ringside seats to all of his title defenses and taunting the champion. In 1908, Australian Hugh “Huge Deal” McIntosh saw an opportunity and offered a substantial purse of $30,000 plus film rights to Burns to fight Johnson in Sydney. The deal was sweet enough and Burns agreed. On December 26, 1908, Johnson handily defeated Burns, finally snatching the crown on a Boxing Day to remember.

Already a staple of the newspapers, Johnson now gained the animosity of white boxing fans who called for a “Great White Hope” to take the title away from him. Several contenders failed and many began to plead for Jeffries to come out of retirement, which he did on April 19, 1909, intent on defeating Johnson, his racial motivation explicit, saying, "I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

Legendary promoter Tex Rickard, who had made his name organizing the Gans-Nelson bout, won the rights and offered a staggering $101,000 purse, the largest in boxing history, held in Reno, Nevada. The racial tensions represented by the fight were further fueled by the media, the New York Times wrote, "If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors." And win Johnson did. In the bout billed “The Fight of the Century,” Jeffries failed to effectively challenge Johnson and conceded in the 15th round in order to avoid a knockout. In the wake of the fight, race riots erupted across the country in at least 50 cities with over 25 people killed. Hundreds more were injured.

Johnson relished being the heavyweight champion and enjoyed the extravagant lifestyle his winnings allowed. On September 11, 1912, he opened a desegregated “black and tan” nightclub called Café de Champion in Chicago. This was perhaps the apotheosis of his career, as shortly afterward, his white wife Etta Duryea committed suicide. Within a month, Johnson was seen publicly with Lucille Cameron, allegedly an 18-year old white sex worker from Milwaukee. On October 17, 1912, Johnson was arrested under the Mann Act for “kidnapping” Lucille, as alleged by Cameron’s mother. Since Lucille refused to cooperate, the case fell apart, though Chicago authorities used this as an excuse to shutter his Café de Champion. He was arrested again on November 17, 1912, with the same charges, though this time the prosecution had a compliant witness in former girlfriend Belle Schreiber. His trial began in May 1913 where he would be convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to a year and a day in prison. Upon hearing the decision, Johnson skipped bail and fled to Montreal beginning a seven-year period of exile. On April 15, 1915, while still a fugitive, Johnson lost his title to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING & PICKUPS Cowan’s Cincinnati Office offers an in-house, full-service shipping department which is unparalleled in the auction industry. Shipping costs are provided with your finalized invoice 24-48 hours after auction. For furniture and oversized items, we recommend using third-party services. For more information, contact cowansshipping@hindmanauctions.com. NOTE: All pickups and preview are by appointment only. To make an appointment, please call 513-871-1670 or email cincinnati@hindmanauctions.com Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB