Eyewitness Accounts of the Atom Bomb Explosions at Los Alamos and Bikini Atoll Described in Correspondence Between Members of Washington University's

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 22, 2018

Cowan’s American History: Premier Auction, scheduled for June 22, 2018 is comprised of early photographs, documents, manuscripts, broadsides, flags, and more dating from the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, Late Indian Wars, World War I and II and beyond. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

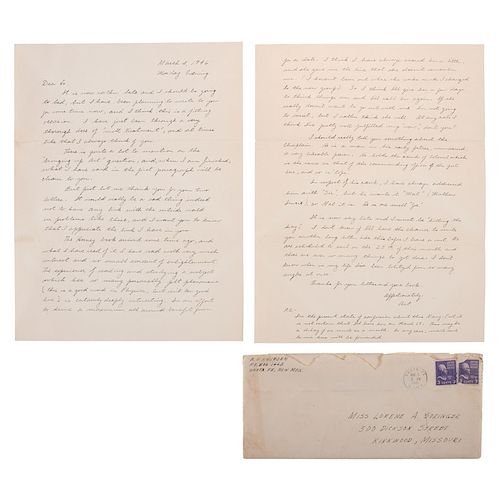

Lot of 4 letters, three addressed to Lorene A. Stringer (1908-1985) and the fourth to Harry "Hoot" Huth (1918-1993) and Lorene Stringer, Dept. of Physics, Crow Hall, Washington University (St. Louis). Huth did classified work on the atomic bomb at Washington University and was a glass-blower, making complicated equipment for the university, especial the Medical School and Physics Departments. Return addresses are all "A.W. Knudsen," and the letters are signed "Art."

The first letter is dated August 13, 1945, from Santa Fe, NM. Most of this letter is very circuitous in its references: "I am still with the group with which I started and from which Harry managed to disengage himself many months ago. The work, though very necessary to the proper functioning of the over-all whole, has never been highly fascinating nor will it ever be, I fear. The problems dealt with make extremely difficult requirements, and their solution lies in a realm of science which, though rather old, is still very approximate. Then I have, for the most part, been not free to tackle the problems in the way I would like, but have been tied down to other jobs which I seem capable of doing, but which don't at all appeal to me.... [W]ith the war situation as it is at present, we really don't know what our future here will be, so It doesn't really pay to plan on much of anything. For all I know I may be back in school for the fall term somewhere, by this coming Sept. or October. In fact this seems all the more likely as a result of what is being announced this very minute. After a false alarm of the Jap's capitulation last night (Sunday) the news of the Jap's acceptance of our surrender terms has just come over the radio a few minutes ago..." He goes on to describe the celebrations that ensued with the unofficial end of hostilities.

"I promised that I'd say something about the atomic bomb. (I still shudder a little to see those two words in print in my letters; the security has been so tight that I can hardly believe I am allowed to mention such things even now). Well, as you know, the first bomb didn't go off over in Japan, but right here in the U.S.A. in New Mexico about 200 miles from here. The number of people who were in on the actual and official observation of the shot was very small, and did not include myself nor Harry. We nevertheless went down to within a hundred odd miles of the firing place to see the show. We went tot the top of Sandia Mountain so as to get a better view."

"The atmospheric conditions were to be as good as possible at the moment of firing so as to bet the best measurements of the blast, etc., so the weather became the controlling factor in establishing the firing time. Originally the tme was set for 4:00 A.M., but at that time our tense little group atop the mountain saw exactly nothing. Nothing at 4:30, or 5:00 either. We decided that the weather conditions must have caused a postponement of the shot, so at about 5:15 we mad the much regretted mistake of heading home. We were just about 15 minutes down the back side of the mountain when we noticed the sky light up with a most terrifying reddish violet color. I would say that the flash lasted only a fraction of a second, but the other fellows insist it lasted several seconds, so I suppose that was the case. My first and about only thought was that the thing really was a success. It worked! --and it must have worked well. (Later evidence bore this out beyond our wildest dreams)."

"After about 9 1/2 minutes, the sound of the shot reached us, and, although the other fellows said that they heard the noise, I, who happened to be speaking at the time, didn't hear it. It must have been a loud noise, we reasoned, if the sound could be heard 115 miles away. (It was actually heard much farther away than that)."

"The brilliant and terrifying flash of light in the sky was all that I could claim as witness to the firing of the first atomic bomb, but some friends of mine, who were from six to 20 miles away, have perfectly amazing tales to relate. My boss, who was about 8 miles away was so overcome that he sank to his knees and finally fell headlong into the mud. When the intense wave of heat hit him he believed he would be burned to a crisp in an instant..."

"When I put together all these stories that I have heard, and then try to imagine the whole awesome affair taking place in a crowded city such as Hiroshima or Nagasaki, I have no difficulty in understanding why the Japanese surrender offer was so quick in coming..."

The second letter is also from Santa Fe, dated March 4, 1946. The early part has to do with a book she sent him to read. "Your proposal of my taking a vacation (a real vacation) this summer is certainly a good one, but I am afraid I have committed myself to an undertaking which pretty well messes up matters. I have agreed to go in the big Navy Atomic Bomb test this spring and summer...We will be sent out to the Pacific (Marshall Islands) and live aboard ship for several months which will be a truly wonderful opportunity. Then there will be two atomic bombs set off (one in the air, and the other either on the water or underneath), and it looks as though I will have the chance to see at least one of these." He continues detailing the increase over the Los Alamos base pay for participating in the tests. Most of the rest of the letter concerns his attempts to get up enough nerve to ask out a girl there.

The next two letters are from Bikini (Marshall Islands). The first is dated May 9, 1946, and describes a lot of his trip out to the Marshalls. They flew (Army transport) from Los Alamos to Long Beach. "...It was only a matter of a few hours after leaving Los Alamos till we were in our living quarter aboard our ship (also our home for the next several months) - the U.S.S. Cumberland Sound..." Just before this he notes: "I was told that the trip was not unusually rough, but my stomach seemed to have other ideas. If nothing else, the last 2 or 3 weeks have convinced me that my stomach is an unusually sensitive instrument for motion detection." He describes life aboard ship ("...strictly Navy...") and notes that everything is metal, which becomes an issue even in the laboratory if someone drops something on the floor in the lab above them. He also notes that there is a lack of right angles - every room is a bit "irregular," and that seems to bother him.

"It would not be doing the Navy justice to refrain from mentioning how good the food is. Compared to the stuff the Army fed us - well, there just isn't any comparison. We civilians aboard this ship have the status of officer. This means essentially that we live in officers quarters and eat in the officers mess. There is some prestige in this in that we eat at tables covered with a cloth; we eat from real plates instead of tin trays....But, what is most important, the food is good."

He then returns to his description of the journey, including a stop in Hawaii, with which he was very impressed. Then he describes the Marshalls with their central lagoon (waters much more to his liking than the open ocean). They live and work onboard ship and go on Bikini for recreation (swimming only on the inner beaches). While in the islands, their only connection to the outside world is the teletype. The messages are run on a mimeograph machine and they get a daily "newspaper."

As usual, he inquires about "Hoot"" and how things are going at the cyclotron. "It looks pretty certain that I shall be going to the University of Chicago after this test is over. I have been offered and I have accepted a graduate fellowship in Physics..."

The last letter is dated July 23, 1946, just after the first bomb was dropped on Bikini atoll (the "air test"). This letter has the most extensive description of the first test of newer bomb designs after the end of the war. The first pages describe the explosion as seen from 18 miles away. They were issued very dark glasses so they could look directly at the explosion, but they seem to have been too dark, so Art removed his. He notes that the cloud was impressive, even at 18 miles. "But perhaps its most impressive aspect was its color. It looked for all the world like gigantic pieces of peach ice cream."

He continued the letter several days later. "In the over-all picture, I should say that the air-drop test was to me a little disappointing. The great atomic bomb, which could wipe out practically whole city, sank only 5 ships - and one of those could conceivably have been prevented from sinking. The target ship, the 30-off year old Nevada, was only superficially damaged: ...Of all the animals employed in the test, only 15% had died after several weeks. The whole thing didn't seem so 'super' to me." (He then notes that the bomb landed 700 yards off target.)

At the same time, he had seen reports of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He then goes on to analyze what he thinks is possible with a bomb under different conditions: "I made some calculations the other day, and here's what came out: if the atomic bomb used all its energy in lifting the Nevada (assumed to be a 35,000 ton ship) skyward, she would go up 200 miles! This is impossible, of course, but other more sober possibilities are almost as amazing. If for example, the bomb used only 1/1,000th of its energy against the Nevada, she would still soar to something like 2,000 feet. I personally have great hopes for the Baker expt. (experiment), and not the least of these is that of seeing large fractions of the battleship Arkansas and the carrier Saratoga soaring high in the air. There will also be tons of water thrown high in the air to add to the spectacle, and I'm hoping the water won't too much obscure the big chunks of metal."

He tells her not to worry, they will be a safe distance away from this explosion. "(Our ship, by the way, is going to set this one off. Maybe you'll see the name Cumberland Sound in the papers)."

The remainder has to do with their schedule (set off bomb July 25th, wait a few days for radiation to die down, go on the island and survey the destruction, and high-tail it back to the states, no stopping in Hawaii!). Los Alamos by mid-August, St. Louis the 1st of September, then University of Chicago a couple weeks later.

A photocopy of an article from the Washington University Alumni Bulletin (Vol. 15, #1, Sept. 1945) outlines some of the work on the bomb done at W.U. It also mentions several of the men who come up in Knudsen's letters. "Dr. Frank Bubb, head of the department of mathematics, directed research in the Cyclotron after the departure of Dr. Hughes to work on the Los Alamos N.M. project from June 1943 to August, 1944. Others who worked with him were Dr. Harry Fulbright, H. Meier, A. Knudsen, S. Kasten, Frank Kirtz, H. Clark, J. Porter, Albert Schulke, Harry J. Huth, Miss Lorene Stringer, Dr. Martin Kamen, and Mrs. Muriel Knovicka. ..."

The second Bikini bomb - Baker - created what the head of the Atomic Energy Commission, called the "world's first nuclear disaster." The ships were too badly contaminated to be used again, and were sunk in the lagoon. The atoll remains uninhabitable today. It should be noted that this entire "experiment" was no small exercise, as one might conclude from Mr. Knudsen's letters. The Navy mustered 242 ships with 42,000 personnel for this test (not counting the 95 target ships in the lagoon).

Most very good, as they have been archived in their covers (which have taken most of the "brunt" of scuffing, soiling, etc.).Condition

Eliminate the Hassle of Third-Party Shippers: Let Cowan's Ship Directly To You!

If you'd like a shipping estimate before the auction, contact Cowan's in-house shipping department at shipping@cowans.com or 513.871.1670 x219. - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB