Elmer Sperry, American Inventor and Father of the Gyro Compass, Photographic and Manuscript Archive

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

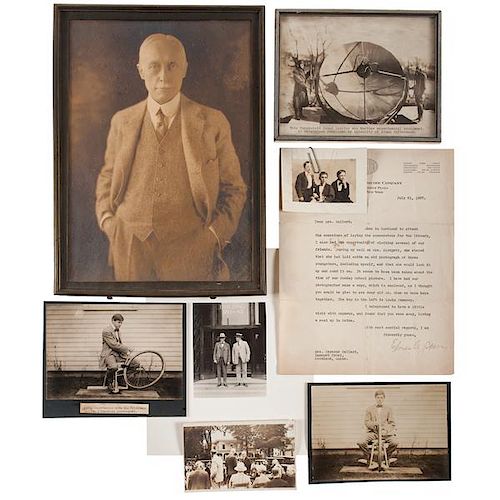

Elmer Sperry, American Inventor and Father of the Gyro Compass, Photographic and Manuscript Archive

Born just before the Civil War, Oct. 21, 1860 near Cortland, NY, Elmer Sperry (1860-1930) showed natural mechanical skills even as a young child. In high school he excelled in science and drawing, the latter being useful in designing and explaining his inventions. At 19 he had invented an arc-lighting system, with help from local Cortland Wagon Company. He moved to Chicago to sell his system in the Sperry Electric Company. The business ultimately failed because of competition from larger, better-funded companies, but the venture taught him the importance and basics of automatic controls and feedback systems, which became the focus of many future inventions.

Sperry’s second venture was a company focused on research and development. He avoided manufacturing, choosing instead to sell production rights to his inventions to other companies. And invent he did. By the time of his death in 1930, he had between 350 and 400 patents. He was also successful because he got into several areas on the “ground floor” – electric light and power, mining, streetcars (electric), automobiles, batteries, - and researched fields that were attracting investors. His research often focused on problems that had held back earlier inventions.

In 1888 he founded Sperry Electric Mining Machine Company, then Sperry Electric Railway Company (1890). By 1894 he had an electric automobile powered by battery. He established an electromechanical research company with C.P. Townsend around 1900, and shortly after, Chicago Fuse Wire Company was formed.

In 1907, Sperry became interested in gyroscopes that had been invented to help stabilize ships to prevent rolling. While others had invented “gyrostabilizers,” Sperry added motion sensors, motors to amplify the effect on the gyroscope and automatic feedback and control system, all improving the existing invention. His market research told him the Navy was building mammoth battleships that could only be effective with stabilizers. The Navy also provided financial and technical support to build them. By 1910 Sperry Gyroscope Company was started back in Sperry’s home state, with offices on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, to specialize in gyroscopes, inventing gyrocompasses, airplane stabilizers, gunfire control systems, torpedo guidance, and automatic pilots for airplanes – and all relied on automatic feedback and control systems. This company also led to Sperry’s greatest inventions in some peoples’ view.

WWI came along near the end of the decade (for the US, earlier for Europe) and European powers also relied heavily on Sperry gyroscopes – Britain, Russia, and even Germany. At the time, as an inventor, Elmer Sperry was second only to Thomas Edison in public recognition. During the war, he increased his involvement in aircraft components, including bomb sights and fire control systems. After the war, he focused on “re-inventing” his systems for peacetime uses – searchlights developed to locate incoming aircraft became signal beacons, initially for the new airmail system, for example. By his death in 1930, the powerful in politics and business would take his calls or meet with him.

In 1939 the US government purchased land in Nassau County, NY, near Lake Success, to house Sperry Gyroscope and other companies essential for the war many knew was coming. During WWII the company prospered, even though its founder was gone. It ranked 19th in the nation in wartime production contracts, developing an analog computer to control bomb sights, airborne radar systems, automatic take-off and landing systems, and ball turrets.

In 1950 a large part of the company moved to Phoenix, AZ, to preserve parts of the defense capability in the case of nuclear war. Also during this period, from 1946 to 1952, the massive Lake Success plant served as temporary United Nations headquarters, until its new home was built in Manhattan.

After the war, Sperry built on its research and produced a digital computer, SPEEDAC, in 1953. Two years later it acquired Remington Rand, which had developed ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator) for the US Army (to solve ballistics problems), and purchased a company that produced BINAC (Binary Automatic Computer). Changing the name to Sperry Rand, the company built on earlier technology and acquired other companies. It went on to market the UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer). The first UNIVACs were delivered to the Census Bureau. For the general public in these early years, “UNIVAC” meant “computer.” Most large corporations acquired a UNIVAC 1100 by the mid-1960s. The UNIVAC 1103 introduced the first commercial use of random access memory. Sperry Rand was so tied to government contracts, however, that in short order, IBM blew by them in the private sector. (One can only wonder if that would have been allowed had Elmer Sperry still been around.)

Sperry Corporation is now part of UNISYS, and Sperry Marine is part of Northrop Grumman. These points in the life of the company are significant for the ledger offered as Lot 226.

An extensive archive comprised of over 1200 items, primarily photographs, but also documents, correspondence, books, and imprints documenting the professional and private life of Elmer Sperry as well as members of his family. Based on the content of a portion of the correspondence included in the archive as well as the manner in which many of the photographs are presented (accompanied by typed, descriptive labels), we believe that the material was collected with the intention of publishing a biography on the inventor. Many of the letters and photographs are addressed to or annotated by Sperry's employee and son-in-law, Robert B. Lea, who was in the process of researching and writing a biography about his father-in-law during the second half of the 20th century; however, it appears that the biography was never completed.

The archive was acquired from the estate of Elmer Sperry's grandson, Sperry Lee, Washington, DC.

Although approx. 1150 photographs dating from the last quarter of the 19th century through the mid-20th century are included in the collection, the highlight is a group of 10 original photographs of Sperry taken ca 1875-1930, starting with a cabinet card portrait of Sperry as a young man, with a Prince, New York and Washington, DC studio imprint; 2 formal photographs of Sperry, 9 x 12.5 in. and 4.75 x 7 in. respectively, ca late 19th-early 20th century; 4.5 x 3.5 in. photograph featuring Sperry with his family; 4 x 4.75 in. photo showing Sperry explaining an invention to his sons as well as a view of him posed with the 36 in. Navy Searchlight; 5.25 x 3.25 in. snapshots of Sperry in an automobile, working on his front porch, and in the midst of a large gathering at the center of a town; 6.5 x 9.5 in. photo capturing Sperry with a woman, presumably his wife; and several 2.75 x 4.5 in. views of a large residence, possibly Sperry's home, as well as a photo identified as the Sperry Farm. An additional 20+ copy images and/or later prints of Sperry (with some that appear to have been made from the original negatives) taken throughout his life accompany the lot, including multiple views of Sperry as a young boy, such as a 4 x 3 in. copy view of Sperry and two friends clipped to a typed letter signed by Sperry to a family friend, dated July 21, 1927, in which he notes that it was likely taken at the time of their Sunday School picture; 8 x 10 in. enlargement of a group of children, including Sperry, again believed to be for Sunday School; at least 6 copies of a photo of Sperry as a young man working on a set of blueprints with another gentleman, ranging in size from 6.25 x 4.5 in. to 10 x 8 in.; and images of Sperry later in life, most 8 x 10 in., many taken in the workplace, with a few photos in which he demonstrates his famed inventions, such as the gyrocompass, and a portrait of Sperry posed with other noteworthy inventors in the Hall of Franklin Institute, Philadelphia.

The collection is comprised of over 1000 family photographs, many of which lack identification. Ranging in size from 1.5 x 2 in. to 8 x 10 in., the majority date from ca 1900-1950, and are snapshots of family gatherings, parties, athletic competitions, vacations, sweethearts, and more. Over 200 photographs appear to have been taken during World War II, capturing views of the people, places, and sites of Japan, as well as soldiers overseas and returning home at the close of the war. Approx. 60 aerial photos also accompany the lot.

An additional 20+ photos featuring Sperry's associates and fellow inventors are included as well as a view of the Sperry Building in Brooklyn and approx. 50 photographs and copy images of various models, machines, and products that were produced by Sperry's company, many with typed captions. It appears that these images may have been considered as illustrations for the biography on Sperry and his company's accomplishments.

At least 10 photos and copy photos show Sperry's children, based on accompanying identifications: 4.75 x 3.75 in. copy shot of his children riding in a horse and buggy; 6.25 x 5.25 copy of a formal family portrait; and 10 x 8 in. press photo showing Elmer Sperry, Jr. and Lt. M. Huggins posed with gyroscopes. At least 5 photographs feature Sperry's third son, Lawrence (1892-1923), who had a similar penchant for tinkering and inventing, including a 4.75 x 3.75 in. mounted photo of Lawrence in 1909, driving an automobile; 3 mounted photos, 6.75 x 4.5 in., showing Lawrence experimenting with the gyroscope; and 10 x 8 in. copy shot of Lawrence's first aeroplane, which he constructed at the age of 19.

The archive also includes 15+ letters written by Lawrence to his mother and father while he was away at school in Arizona, most dated 1911-1912. In one letter, Lawrence wrote to his father, I am glad to hear you are rapidly completing the first gyro compass for Mss(?) "Utah." Will you finish it in 90 days? Everybody out here seemed to know without speaking that you built the first gyro compass. Arelie says he'll try to keep his old-man asking for more battle ships so you will keep busy making compasses (November 12, 1911). Some of the letters are decorated with unique pencil sketches.

After witnessing a flight by Henri Farman in 1909, Lawrence was determined to build his own airplane. While his family left on vacation, he and his brother transformed their family's home into an airplane workshop. He went on to become a pilot and inventor, producing the first autopilot, which he demonstrated with great success in France in 1914. Lawrence is also credited with developing the artificial horizon still used on most aircraft to this day. On December 23, 1923 Sperry took off amid fog in a Verville-Sperry M-1 Messenger from the United Kingdom headed for France, but he never reached his destination and Lawrence's body was found in the English Channel on January 11, 1924.

The archive also features the following highlights:

Notebook containing reprints of patents 715,801; 730,320 (1902); 772,680 (1904); 847,526; 873,699; 875,632 (1907); 877,261; 879,596 (1908); and 967,900 (1910).

Notebook with 62 typed pages, including quotes from Sperry, letters about early businesses in Chicago and Cleveland, and his move to Brooklyn. A significant portion describes Sperry’s electric cars and the electric vs. oil power conflicts. Last page with 4 photographs, 3 x 4.5 in. with Sperry plant enlargement, an early automobile (presume one of Sperry’s electric cars), an aid for Sperry Air Compressors, and the interior of a plant.

Wiley Post TLS, 1p. Thank you letter to Sperry Corp. for Automatic Pilot. On City of New York, Floyd Bennett Field letterhead, Aug. 2, 1933. In the letter, Post states that his around-the-world flight would not have been possible without the automatic pilot. Accompanied by 2 photos of Post and his plane.

Photos of U.S. Navy “Flying Boat” – several letters concern identification of men standing near the aircraft.

Notebook with Goodman family genealogy (Elmer Sperry’s wife was Zula Augusta Goodman), her father’s early life. Ch. I – Chicago 1880-1885 (focus on electric lighting); Ch. 2 – 1886 (Still Chicago); Ch. 3 (marked II) - Chicago 1886-1893; Ch. 3 – Chicago Companies, with hand-drawn chart of various Sperry Cos. of the time (Chicago). 48pp (42 – geneal. [iii], 25a, 25b & chart).

Folder of copies of letters, etc. – including one with manuscript note, “transcriptions of ltrs 1898 trip to Paris with Elec. Auto.” Copy of article by Francis Sill Wickware (“Elmer Sperry and his Magic Top”) [had been accepted by Readers Digest] (mentions another article in Fortune that he wrote on Sperry).

ALS to Robert Lea from R.L. Boyer, Cooper-Bessemer Corp., Mt. Vernon, OH, October 2, 1961. Boyer states in part:…I have said many times that Mr. Sperry was one of the world’s greatest inventors and that he certainly exceeded Edison. This always comes as a surprise to the listener for of course Edison is thought of as being America’s greatest contribution to science. Actually Mr. Edison mainly worked on comparatively simple things even though the outcome was, in so many cases, a great accomplishment for mankind. There is nothing very complicated about the incandescent lamp, the movie machine, or the phonograph. They have contributed greatly to the comforts and enjoyments of people the world over but they are so relatively simple that if Mr. Edison hadn’t thought of them when he did, I am sure someone else would.

On the contrary, Mr. Sperry delved into things that were so scientific and so involved that the public little understood him. The development and application of the Gyro principles are still beyond most people and, although the benefits to mankind have been just as great or even greater, the public little understands the principles and certainly doesn’t know where the original thinking came from.

Series of photos of sketches by Alfred Crimi and one page explaining hiring him in to draw several Sperry developments.

A number of printed memorials to Edward Sperry, including 13 copies of a tribute written by Anne Lloyd, which were produced in Italy.

Two copies of J.C. Hunsaker.“Biographical Memoir of Elmer Ambrose Sperry 1860-1930. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, 1955. 8vo, printed paper wraps, 40 pp. One copy has lists of all of his publications and patents cut out of the back; other one complete.

Dunn, Gano, Saunders, W.L. and Fiske, Bradley. “A Narration of the Engineering and Scientific Achievements of Elmer Ambrose Sperry, John Fritz Medalist for 1927.” N.p., Awarded Dec. 7, 1927. 8vo, printed paper wraps, 54pp.

Program for “Memorial Exhibit to Elmer A. Sperry. December First to twenty-Seventh 1930.” New York: Presented by the Museum of Science and Industry. Single sheet folded (4 printed pp.)

Sperry Gyroscope Company, Brooklyn, NY – form for Manufacturing, Performance, Purchase, Sales, and Test Specifications, 5 pages (carbon copy), pinned together. For “Sperry Dead Reckoning Tracer System…for Normal Speed Ships.”

Copy of article by Sperry from 1879 in The Normal News, on “England and America as Manufacturing Competitors.”

Copy of Robert Lea obituary (1891-1968) – “He is survived by his widow, the former Helen Sperry… two grandchildren, Helena and Robert Brooke Lea II.”

Copy of Chs. IV – VII of biography.

A number of blank examples of various Sperry company letterheads.

Book containing photos of an exhibit on the top floor of Sperry HQs in Lake Success called “Of Fundamentals …. And Man.”

Newspaper article on “Famous Fathers Famous Sons," focusing mostly on Elmer A. Sperry – affixed to 5 pages of black paper.Very good, some toning of the paper but most images are in good condition.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB