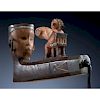

Eastern Great Lakes Carved Effigy Pipe Bowl

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Oct 11, 2019

The October 11 American Indian & Western Art: Premier Auction features an outstanding assortment of material from collections of Plains and Plateau peoples, Southwest, Inuit, early Navajo textiles, and two exceptional early tomahawks. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

walnut, bowl is carved in the form of a human head; a smaller figure is seated on a chair with a barrel keg in hands; hide thongs attached at ears are wrapped with metal wire; lead inlay, length 5.5 in. x height 3.25 in.

fourth quarter 18th century

Stone bowls of the type were produced by the Ottawa and Ojibwa Indians of Manitoulin Island in the ca 1820-1850 period (Brownstone 2011). The large number of such stone pipe bowls made there in that period suggest a virtual florescence of pipe carving, assumed to be stimulated by the demand of White travelers. But this example was carved of wood, and several details suggest that it predates the Manitoulin Island production.

There is both archaeological and early historical evidence that the carving of wooden pipe bowls once was common in the Great Lakes region. The introduction of steel knives may have stimulated an increased production of stone pipes, and the gradual disappearance if wooden ones. A pipe bowl carved of wood would have been considered as very old-fashioned in the early nineteenth century.

Since early colonial times, the wooden pipe bowls were often lined with metal; sheet brass in the 17th century, replaced by molded lead in the 18th century. Lead inlay decorates also stone carvings, but the technique was no longer resorted to by the Manitoulin Island carvers in the 19th century. Other evidence of an earlier date for this example is presented by the treatment of the ears on this pipe’s figurines; the slicing of ear rims and winding helixes with metal was no longer fashionable in the 1830s. Only two other pipe effigies with such ear decorations have been found, both undoubtedly dating back to before 1800 (Feder 1971: figs 89, 124). One of those pipe bowls was carved of wood, and both show lead inlay, shape of the shank and carving of the human head similar to the example discussed here, i.e. of an Ojibwa-Ottawa type.

Remarkable in the carving of the sitting man is his erect penis. Sex and its erotic details have become confused and confusing subject in Western Civilization, but in tribal societies a more relaxed attitude prevailed. The phallic human figure on this pipe bowl may be unique, but this detail has been noticed on certain carved wooden figurines on the Minnesota Sioux; a Potawatomi “love doll” in private collection; a rawhide phallic human figure used to hang on the center pole in the Sioux Sundance lodge; phallic details are noticeable on the earliest surviving war record paintings from the upper Missouri River; and a large wooden penis was carried around by a dancer in the Okipa Ceremony of the Mandan Indians.

Some of these examples were symbolic of fertility; others may relate to sexual intercourse as a medium in the ritual transfer of spiritual power. Though most of these examples relate to more western regions, there is some evidence that long ago sex played a role in certain rituals of the Eastern Woodlands as well. Arni Brownstone (2011:59) followed Ewers in assuming that sexual activities pictured on Plains Indian effigy pipes were made to appeal to American clients. This may well be true for some of those carvings, but it does not explain why [the figure] is sitting with an erect penis. It is possible that this situation was understood as an expression of great excitement.

The use of chairs by the native peoples was rare before their settling in reservations. A chair was carved on one of the Manitoulin Island pipes in 1845 (Brownstone 2011: fig. 2); small tables show up on some effigy pipes made by the Minnesota Sioux in the same period, and Ewers (1986: 91) pictured a similar effigy pipe, supposedly acquired from Iowa Indians. The use of such furniture may have been an indication of prestige in those early days, as was the placement of the chair on a mat. The rectangular platform on this pipe probably shows the special mat on which pipes and wampum belts were placed during ceremonials.

Sufficient details have been discussed so far to identify this exceptionally fine pipe bowl as an Ojibwa or Ottawa carving from the eastern Great Lakes region. The use of wood, lead inlay, and ear decorations suggest a production pre-dating the Manitoulin Island pipes of the 1840s, possibly placing this example in the 1780-1800 period. The stems used with such pipe bowls were either wooden tubes, often wrapped with colored porcupine quills, or made of flat wood, often decorated with pierced motifs (“puzzle stems”).

Pipe bowls decorated with images of animals or human figures have a long tradition in the eastern Woodlands. The most important effigy – frequently a human head – is invariably facing the smoker, and considerable evidence indicates that such effigies represent personal guardian spirits or the spiritual patrons of religious cults. Facing the smoker, these figurines served as a focus of meditation in a mental communication with the spirit. This explains the often-reported native custom of spending long hours in pipe smoking. The ritual function and symbolic connotations of tobacco in native society are well known and do not need to be summarized here. Pipes were carved by the men, who also took care of the tobacco gardens. Women tended the regular food crops.

Arni Brownstone (2011) suggested that the production of effigy pipes on Manitoulin Island was stimulated by the demand of early White tourists, in view of the considerable quantity of these carvings. In view of the local presence and influence of missionaries and government authorities the predominant reference to “pagan” customs and beliefs in these carving is remarkable though. Native religion and its public ceremonials were undoubtedly still strong there, and it may well be that the prolific production of “pagan” carvings was a form of a silent resistance against Christian influence, as known from other religions. That White tourists were eager to buy such souvenirs was undoubtedly a welcome source of income, but it may not have been the primary motivation.

This brings us to a discussion of the enigmatic keg held up in offering to the spirit, pictured by the large human head on this pipe bowl. From earliest contact with Europeans, alcohol was among the most valued gifts given to the Indians in political and commercial negotiations. Traders use to dilute the rum in order to lower the costs of their generosity. In time, the drinking of spirits became an integral part of some religious ceremonies, producing a short-cut to “visionary” experience. Rum kegs held up by human figures decorate several early pipes and some spoon handles of the Wyandot Indians. It is suggested that these images refer to the liberal consumption of rum in the annual meetings of shamanistic curing organizations of the Wyandots, called the White Panther or Lion Society (Barbeau 1915: pp. 95-97, 342). Warfare in the seventeenth century dispersed the Wyandots to several locations in the Great Lakes region, where they lived in intimate contact with the Ottawa and Ojibwa Indians. By the end of the seventeenth century, a shamanistic curing organization emerged among the Ojibwa, called the Midewiwin or Grand Medicine Society. The ceremonials of this cult indicate a thematic and perhaps historical relationship with the White Panther cult of the Wyandot Indians. The effigies used on Ojibwa pipes, including the rum kegs, suggest that they were part and parcel of the Midewiwin.

T.J. Brasser 2018

Examples of effigy wood pipes of the Iroquois and Eastern Great Lakes in the 17th – 18th century:

National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen. Cat. Dc-16, Cat. Egc-4

Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland. Cat. 43.0871/ 1796

United States National Museum, Washington, D.C. Cat. 10080

McCord Museum, Montreal. Cat. M11030

Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation Cat. 24/473.

National Museum of Ireland, Dublin. Cat. 1902.353, Cat. 1902.359

British Museum, London. Cat. D.c.80; Cat. D.c.44

Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau. Cat. III-G-799

References:

Barbeau, C.M. “Huron and Wyandot Mythology”. Department of Mines Memoir 80, Ottawa, 1915.

Brasser, T.J. “Self-Directed Pipe Effigies”. Man in the Northeast. Vol. 19, Spring 1980.

Brownstone, A. “Mysteries of the Sculptural Narrative Pipes from the Manitoulin Island”. American Indian Art Magazine. Vol. 36-3, Summer 2011.

Dockstader, F.J. Indian Art in America. 1961.

Ewers, J.C. Plains Indian Sculpture. 1986.

Feder, N. Two Hundred Years of North American Indian Art. 1971.

King, J.C.H. Smoking Pipes of the North American Indians. 1977.

Vincent, J.T. et al., eds. Art of the North American Indian: The Thaw Collection. 2000

Included is a hardcover published report of this pipe written by Alan L. Hoover and Theodore J. Brasser, Powerful Exchanges: Diplomatic Gifts from the 1760 - 1840 on the Eastern Frontier - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB