Early Civil War Correspondence, Letters Written By Hervey Batcheller from Paris to Boston, 1861-1862

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

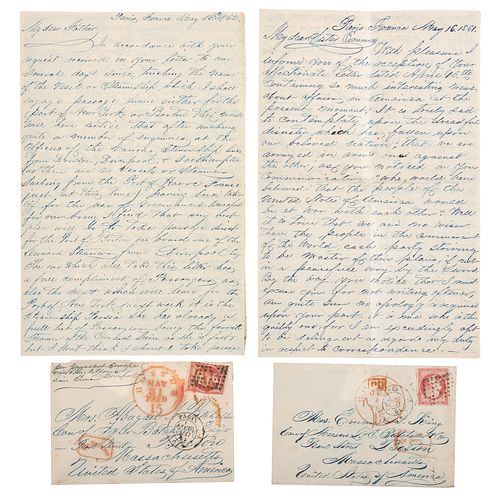

Early Civil War Correspondence, Letters Written By Hervey Batcheller from Paris to Boston, 1861-1862

Lot of 11 letters written by American ex-patriot Hervey Jenks Batcheller (ca 1826-1865), sent from Paris to his family in Massachusetts during the early years of the Civil War, 1861-1862. Batcheller hears of the war’s outbreak whilst abroad and is forced to rely on family correspondence and English-language French newspapers for coverage of the unfolding national crisis. Letters contain Batcheller’s eloquently recorded impressions of the Trent Affair, the general lawlessness of Confederate privateers, the evacuation of Nashville, the unprecedented naval battle at Hampton Roads, and Confederate diplomacy with European dignitaries. Accompanied by original covers franked with French imperforate 80-centime stamps of Napoleon in profile.

The date of Batcheller’s departure for Paris is unclear, but he applied for a passport in 1855. By this time, Batcheller had entered into the prosperous shoe manufacturing firm established by his father, Tyler Batcheller (1793-1865). The company had offices in both Boston and the family hometown of North Brookfield and brought in $1.5 million annually. Hervey Batcheller left the company in 1860, presumably departing for Paris at some point between the time of his resignation and the date of his first letter, May 16, 1861. Here, he shares with his sister, Emma King of Boston, his initial reactions to the declaration of war: “It is truly sad to contemplate upon the dreadful disaster which has fallen upon our beloved nation; that we are arrayed in arms, one against the other.” He expresses confidence in the Union, stating that “the North [has] come out so united, and in such force, that it will be likely to overawe the South, and cause them to think before they enter upon their rash attempt to destroy the Union. But they have some desperate men among the leaders of this rebellion. . . I expect Jeff Davis has got a large army in the background. More than the North have the least idea about, for we only see one side of the field at present.”

The reality of the conflict finally seems to reach Paris by the end of May, and Batcheller tells his family of general unease within the ex-patriot community, citing two incidents in particular: “Only last week a young man from Philadelphia, who has been here some time with his family...was talking quite energetically [about the War]...all of a sudden he fell back in his chair with an epileptic fit...[And] only yesterday another was so excited that he went into a pistol gallery and shot himself through the head, blowing his brains in all directions...that might be a more agreeable death than to fall into the hands of one of Jeff Davis’s Pirates at war?” Confederate privateers or commerce raiders were privately owned ships authorized by the CSA government to attack United States shipping vessels and seize their cargo. This tactic also served to divert the attentions of the Union Navy away from the blockade of Southern ports and perhaps to encourage European intervention in the conflict. Speaking to the latter point, Batcheller writes that “there are many [here] who say that they would not risk going to America now for fear of being taken by one of the privateer ships. It is said that quite a number of vessels are filtering over upon this side of the ocean to go in search of American vessels or steamers but I think that the English and French governments will keep a good look out to prevent any departure of armed vessels...[though] there is some prospect that [the CSA] may yet be recognized by England and France, the Southern Commissioners are to have a hearing before the Emperor this week (so it is reported).”

The Confederate Army began to gain ground in the summer of 1861, and the solemnity of Batcheller’s letters form this time reveals his growing concern for his country. On July 9, 1861, he writes: “It looks more as if the war might be long and desperate. This last victory gained by the South rather changes the tone of journals on this side of the ocean – from the leading articles in the English and French dailies, one could be led to believe that now the South will have a change to gain.” Later, on November 28, 1861, Batcheller shares news from London of the arrival of the packetboat RMS Trent, the linchpin of the Trent Affair, a major diplomatic incident that threatened war between England and the United States: “‘Trent’ [was] met in the Bahama Channel by the ‘San Jacinto,’ the American war steamer in pursuit of the commissioners sent by the Southern Confederacy to Europe. Messrs. Mason and Slidell, it now appears that they were taken...It may cause some difficulty between out government and England, as also another steamer from the rebels called the 'Nashville' which ran the blockade at Charleston, has now arrived in the English Channel...after capturing and burning a vessel from New York called the ‘Harry Binck.’ Some say that the English and French governments will now recognize the Southern confederacy. . . out of spite, on account of taking Mason and Slidell by force from off their steamer, they may even go so far as to declare war against us.”

By the spring of 1862, however, a series of Confederate defeats seemed to refortify Federal forces. On March 7, Batcheller writes to his father, sharing his excitement over “the most glorious news of continued successes in putting down this most wicked rebellion.” The Confederates had surrendered Forts Henry and Donelson in February and evacuated Nashville by the end of the month. Batcheller relates that these Union victories “take the Europeans by surprise, for they began to think and write in their daily journals that it was all up for the ‘Grand American Republic.'" He comments further on the biases of European reportage, writing in part, “It was intimated that the London Times. . . so down upon our war, government, and everything else American (except for the cause of the Rebels and the disruption of our Union), would come out in ‘full mourning’ for the South as they did for their Prince Albert; however, they did not give an article in today’s journal touching these brilliant victories of the Federal Army – had the South gained the slightest advantage, they would be sure to come out and magnify it to a ‘splendid, tremendous, magnificent’ defeat of the Yankees and victory of the ‘chivalrous southerners.’” Later in March, he shares his reactions to the “exceedingly interesting...news from the seat of war in America...of a great battle in Tenn[essee] & Miss[issippi] of a dreadful destruction of life, etc...we think that it is somewhat exaggerated, 40 thousand rebels and 20 thousand federals killed, etc. We fear that the steamer 'Merrimac' will come out and destroy the fleet of Federal vessels now on the blockade.

Content from later letters includes the capture of New Orleans and the repulse of General Nathaniel Banks at Winchester, though Batcheller’s primary focus is securing passage home. He suggests that this process is difficult, as most sailing vessels “have been taken off for the use of government transport for our army.” He discusses various departure options, but his plans are seemingly foiled by his own poor health. Records suggest that he died at sea, sometime during or shortly after 1865. - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB