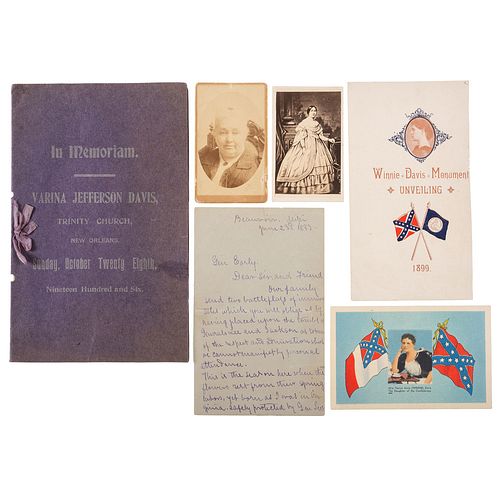

DAVIS, Varina (1826-1906) and Winnie DAVIS (1864-1898). A group of 6 items, incl. CDV signed by Varina Davis.

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 25, 2021

The June 25 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction features an exciting assemblage of 18th-early 20th century material, including Civil War archives, Early Photography, Western Americana, Autographs and Manuscripts, and more. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

CDV of Varina Howell Davis, widow of Jefferson Davis. Inscribed to Mr. Frank Binns on verso and dated February 14th, 1903 (77 years of age).

CDV of a lithograph of Varina Davis as a young woman. She is in a standard studio setting. On verso "Mrs. Jeff Davis." No photographer's ID.

Memorial program for Varina Jefferson Davis (1826-1906). 6 x 9.5 in., purple printed wraps, ribbon tied spine, 4pp.

Varina Anne ("Winnie") Davis (1864 - 1898) ALS, 2pp (4.25 x 7 in.). Beauvoir, Miss. June 23d, 1883. To General Jubal Early.

"Dear Sir and Friend, Our family sends two battle flags of immortals which you will oblige us by having placed upon the tombs of Generals Lee and Jackson as tokens of the respect and admiration which we cannot manifest by personal attendance."

"This is the season here where the flowers rest from their spring labors, yet born as I was in Virginia, safely protected by Gen. Lee's good sword, I feel that something that grew at our home must be offered at the shrine of the men whose valour and genius made our country glorious and whose righteous lives added to their noble deeds in war, and no less in peace, made their names the precious possession of the whole Anglo Saxon race."

"I send two bay wreaths which we may hope will reach you in better condition than flowers would be."

"My Father and Mother unite with me in sincere regard and I am dear Sir,

"Respectfully and affectionately Varina A. Davis."

Color postcard with lithographed portrait of Winnie Davis with a Confederate Battle Flag and last National Confederate Flag on either side. Caption below portrait "Miss Varina Anne [WiNNIE] Davis / The Daughter of the Confederacy." According to the story on the verso of the card, Winnie was the inspiration for the name of the "Daughters of the Confederacy" Association.

Accompanied by a brochure for "Winnie Davis Monument Unveiling (November 9th) 1899." 5 x 7.5 in. At Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, VA). Inside it notes "This monument is erected by the Daughters of the Confederacy. The movement having been inaugurated by the Richmond Chapter and generously responded to by Chapters, Camps, friends, and admirers of Miss Davis, both North and South."

Born in the South, in Natchez, Mississippi, Varina Howell's (1826-1906) nuclear family would have lived in poverty if not for the support of wealthy relatives. They also enabled the family to send her to Philadelphia for her education. There she attended Madame Deborah Grelaud's French School, which has been described as a somewhat unconventional girls' school (in American education, but more like French schools of the day). The young ladies were expected to speak French and studied a rigorous curriculum of history, philosophy, natural science, geography and more, rather than the more typical music, etiquette, needlework, etc. of so many schools for girls.

While in the North, she got to know many of her relatives (her grandfather had been Governor of New Jersey). Even before the Civil War broke out she spoke out against secession. During Christmas in 1843 (at age 17) Varina went to the plantation of family friend Joseph Davis. There she met Davis' younger brother, Jefferson and became intrigued with this older man. Though still mourning his first wife, Sarah Knox Taylor, Jefferson Davis did ask permission to court Varina. Her family balked at first (there were differences, besides age, in politics and background), but finally consented and the couple was soon engaged. They married in early 1845 and moved to Brierfield, land loaned to Jefferson by his brother Joseph. Joseph was in control of much of the Davis family business, and this was especially true of the very young wife of his youngest brother. Jefferson was often away, campaigning, serving in the Mexican War, etc.

Upon his election to the House of Representatives in 1846, the couple moved to Washington, DC, but Varina was returned to Brierfield during Davis' service in the Mexican War. She became so resentful of her treatment there that she initially did not join her husband when he returned to Washington to fill a vacant Senate seat after the war. She finally did return to the capital where she became the life of many parties as one of the youngest hostesses and guests in the political circles and the parties hosted by Southerners were especially lively. She liked the stimulation of the city and social life, although she became known for making unorthodox (for a woman) observations, as the result of her education, which was nearly the equivalent of most of the men.

After a number of childless years, the Davises would eventually have six children, although only two (both daughters) would survive into adulthood and only one married and had children of her own. Their first son died at about two years of age. Jefferson Jr. died during a yellow fever epidemic at the age of 21. Joseph died of a fall at the "Confederate White House" while the family was living in Richmond. And William died of diphtheria just shy of his eleventh birthday.

Although she preferred city life to that on the plantation, Varina was never comfortable in Richmond. She was never really accepted by the residents of that city. She supported both slavery and the Union, and expressed her belief that the South could not win a war with the North. She also thought her husband unsuited for the Presidency and that women were not inferior to men and maybe should be given the right of suffrage, though it is uncertain how widely her views were expressed. Varina is described as having olive skin, thought to be from her Welsh ancestors, but in Richmond rumors started that she was a "mulatto" or "Indian squaw." Clearly her stay in Richmond was not a happy one (and made worse by the death of their son).

The trials of the Davises after the war are well-documented, first their flight from the Confederacy, then Jefferson's imprisonment in Fortress Monroe, his failed attempts at employment after his release and finally the generosity of Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, who had been a classmate of Varina's in Philadelphia, allowing the family to live in a cottage at Beauvoir. Dorsey also left the plantation and finances enough to maintain it to Jefferson Davis in her will. After Jefferson Davis' death in 1889, Varina completed Davis' autobiography, but it did not sell well enough to provide some income for her. Then Kate Davis Pulitzer, a distant Davis cousin and wife of Joseph Pulitzer made arrangements for Varina to publish short articles in The New York World. Later she became a full-time columnist and she and youngest daughter, Winnie (Varina Anne), moved to New York.

Winnie had been engaged to a Northerner shortly after her return from college. But both parents were against the marriage and after breaking off the engagement. Winnie would never marry, remaining as a companion to her mother until Winnie's death. Winnie also became a writer in New York, publishing novels and a biography as well as articles for publications such as The New York World and Ladies Home Journal.

Born in 1864 in Richmond, and quite attractive, Winnie became the symbolic "Daughter of the Confederacy." Her image appeared on everything from advertising to United Daughters of the Confederacy materials. She traveled with her father to Confederate groups of many kinds - veterans, women's associations, and more. When Winnie became engaged to another Northerner shortly before her father's death, pressure from the South, disapproving of "their daughter" marrying into the North, helped to break up that relationship (among other factors). Southerners were also unhappy at the First Lady and Daughter of the Confederacy moving to New York, but the women had no pension or other income and needed to make a living. New York was the center of the publishing world in America. And Varina was certainly happier in the stimulating climate of the big city.

Winnie died in September 1898 at the age of only 34. She had been at a Confederate Veterans' Reunion in Atlanta, then met her mother at Narragansett Pier, Rhode Island, where the women vacationed annually. Winnie became very ill, the doctors diagnosing it as "malarial gastritis." She had suffered gastritis for years. She suffered fever, chills and loss of appetite for over a month. The hotel in which they were staying - the Rockingham - typically closed for the season in early September. But they allowed their regular customers, the Davis women, to remain past closing because of Winnie's condition. She died there on Sept. 18. Varina had Winnie interred at Hollywood Cemetery next to her father and brothers, and with military honors for her service to Confederate veterans. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING & PICKUPS Cowan’s Cincinnati Office offers an in-house, full-service shipping department which is unparalleled in the auction industry. Shipping costs are provided with your finalized invoice 24-48 hours after auction. For furniture and oversized items, we recommend using third-party services. For more information, contact cowansshipping@hindmanauctions.com. NOTE: All pickups and preview are by appointment only. To make an appointment, please call 513-871-1670 or email cincinnati@hindmanauctions.com Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB