CSA Pvt. James Francis Heizer, 14th Virginia Cavalry & McClanahan's Battery, Archive Incl. Correspondence with Fiancée Regarding the Civil War and Po

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 20, 2015 - Nov 21, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

CSA Pvt. James Francis Heizer, 14th Virginia Cavalry & McClanahan's Battery, Archive Incl. Correspondence with Fiancée Regarding the Civil War and Post-War Career as Traveling Photographer

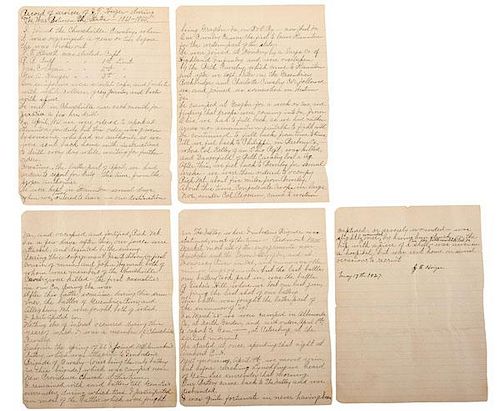

Lot of approx. 146 letters accompanied by the book entitled The Heizer Family: American Pioneers by James Harion Heizer, ca 1861-1868.

On the horrific battlefields of the Civil War beat the hearts of many desperate men struggling to survive the horror to return back to the beauty of home and the arms of their lovers. To retain some of their humanity, they candidly spoke to their sweethearts about their struggles and horrors of war more than they did to their mothers or brothers. One of those men on the field was James Francis Heizer.

Heizer was a private in the Confederate army. Amazingly, he recorded his own account of service in the war. He writes:

I joined the Churchville Calvary when it was organized a year or two before the war broke out...Our uniforms were scarlet caps, and jackets with white collars, grey pants, and boots with spurs. We met in Churchville once each month for a few hrs drill.

In April 1861, we were ordered to report at Stanton for duty, but this order was given by someone who had no authority, so we were sent back home with instructions to drill every day while waiting for further orders.

Sometime, the latter part of April we had orders to report for duty- this time from the proper authorities...Early in the spring of '62 I joined McClannahan's battery, which was attached to the Inbiden's[?] Brigade of the Calvary- (ours being the only battery in this brigade) which was camped near New Providence Church at this time. I remained with said battery 'till Gen. Lee's surrender...I was quite fortunate in never having been captured, or severely wounded - was slightly wounded once, by having been struck on the hip with a piece of a shell in the battle near White Post, VA - was never in the hospital, but was sent home on several occasions to recruit (Heizer, May 17, 1927).

Heizer met his lover, Phoebe, through his brother. It might be that you and I had never become acquainted, had he not requested me to form your acquaintance, and taken me to your father's with him, he explains to Phoebe (April 30, 1864). He developed a friendship and veiled his affection for her. They wrote long letters and exchanged poetic verses with one another. Finally, April 13, 1864, he could no longer hide his affection. In a desperate letter introduced as a typical letter with war news and camp he wrote:

Phoebe, changing the subject abruptly, do you know that my feelings toward you are something more than mere friendship? You have no reason for thinking so from my words, but perhaps you have from my actions, and “actions speak louder than words.” I have no doubt you will think strange of what is contained in this letter, but I see no more necessity in concealing my intentions from you any longer, and remaining in suspense myself. I would greatly preferred talking the matter over with you, but you well know, that circumstances would not admit of it when I last saw you.

Well then, I had intended proposing marriage to you this spring had I not some in service…Rest assured of one thing, I have made no effort to deceive you in any respect, and I am just exactly what I appear to be, and that I am just exactly, what I appear to be, and that I have not hastily arrived at this conclusion. Exercise your own discretion in regard to asking the advice of your parents on the subject, weigh the matter well as I have done, but answer as soon as possible, for we will be on the march shortly, and I may not receive your letter. Should you consent the time will be fixed in the future. I don’t know what the advice of our parents would be. I know not what my fate will be. I expect to be exposed to danger this summer of various kinds, and it may be that my days on earth will be few, but I well know that my life is in the hands of a Just and Holy God.

She accepted his proposal a week later. Elated, he responded:

I have one promise to make. I shall feel it to be my duty and not only a duty but my greatest pleasure to do all in my power to render you comfortable and happy…Whether my life shall be spared to see peace once more restored to our country is unknown to us, but we have the satisfaction of knowing that there is a place prepared for us if we live up to the requirements of God’s law…if we are to meet no more on this earth may we meet in heaven where parting is no more.

Reflecting later on his affections in another letter he wrote to her:

I waited a long time for you to [ask the "all important question"], as it was a leap year, and concluded at last to wait no longer. I gave you nearly six months, and I don’t believe now, you had any idea of such a thing. However as you are young and bashful I saved you that trouble.

They kept their romantic connection with one another a secret from their families not because there was any opposition in Heizer's family (he assured her they would cheerfully accept their match), but as suggested by him and requested by her to wait until the end of the war. To conceal their engagement, Phoebe asked that he burn her letters as soon as answered, and he complied (April 30, 1864).

Seeking a more certain view of the future, Heizer visited a fortune teller. He shared the reading with Phoebe, She said that I was to be married very soon to a fair-haired lady that I had a rival, a man with light hair and blue eyes, but I was to defeat him (March 18, 1862). The fortune teller was correct because a month later his fair-haired rival asked for Phoebe’s hand. Who is he? What is his name? Are you not at liberty to tell me, asked Heizer? Poor fellow! I am so sorry that his offer will have to be rejected (April 30, 1864).

Phoebe slipped a secret love note into a box of cake she sent him. Mother did not know there was a letter enclosed with the cake until I opened it, writes Heizer. I don't think, for I don't believe it had been opened, and as to the some else that you speak of, I don't suppose that they know anything of it...the signature to your last letter amused me as soon as I saw it. I suppose you know who "Flora" is if Miss Bettie doesn't (May 16, 1864).

Heizer, like many soldiers, struggled to maintain his humanity in the midst of so much evil and suffering. He wrote to Phoebe:

Some persons say that a man cannot live the life of a Christian in the army; but I cannot believe it. God is with us as well as in the army as at home and out prayers are never offered in vain…When we lay down to rest with nothing above us save the broad canopy of Heaven, and all is quiet in the camp. Not a night passes, but I spend an hour or two in thinking of any absent friends, self examination and prayer. I often think then is there any one thinking of me? Yes, I know of one whose prayers are daily offered in my behalf. You are the one, It seems that if the war was closed and I could become settled in life I could be the happiest of the happy. We would then be united, I would be your constant companion. It would be my delight to be constantly with you, to support and protect you…(July 15, 1864).

Not all was calm in their relationship. Heizer returned home on furlough and spent many hours with Phoebe, however, she thought it was not enough. She wrote a spurned letter to him. In response, he wrote:

Your last letter caused me considerable trouble and anxiety. You certainly cannot believe that I can ever forget one, in whose society, the most pleasant hours of my life has been spent, and on whom centre all my hopes of future happiness. No! as many faults as I have I do not profess that one, of trifling with the affection of ladies. Let me assure you, you will never find a truer, more devoted friend, than the author of these lines (February 17, 1865).

Near the end of the war Heizer quickly wrote a letter to Phoebe:

Gen. Lee surrendered to Grant last Sunday morning with 17,000 men, and I believe it is the intention to surrender the whole army. The troops what were at Lynchburg Sunday were disbanded and sent home, I have had no opportunity of sending a letter to you since I left home. I expect to see you in a short time (April 11, 1865).

Their tumultuous engagement continued with angry letters penned back and forth. Without consulting his fiancée, Heizer decided to enroll in college in 1866. Enraged from an already extended engagement, Phoebe asked if he wished to be released. He replied, Yes!

They continued to write letters to one another, some dripping with sarcasm or veiled insults. Heizer tried and failed at college. In 1866 he wrote to Phoebe, You will be surprised when I tell you that I have quit school, that I have changed from a student, to an artist (January 22, 1866). After the carnage of the war he peacefully worked as a traveling photographer through small, sleepy towns in Virginia and West Virginia. It was a lonely life and lasted for a short while. He wished to settle down and rekindle his romance with Phoebe. He wrote:

I must acknowledge that I am entirely to blame in this matter…I did not ask to be released from the engagement on account of any dissatisfaction on my part, but because I considered it impracticable to carry out, or execute my plans for several years, and in that time, I did not know what changes might take place…Although you believe that you were the injured party, I do not believe that you have ever spoken an unkind word of me to any one. Can you now consent to be the same to me that you were two years ago? (December 10, 1867).

Phoebe responded, [I] will give you the reply that Gen’ Jackson sent to Santa Ana, “If he wants me, let him come and take me.”

They married in February 1867 and had nine children. Phoebe died at 61 of congestive heart failure in 1906. Heizer’s heart stopped beating in 1930 and the age of 88. They are now together in heaven where parting is no more.

For a detailed look at the contents of the archive, go to: http://www.historybroker.com/collection/heizer/index.htm.Many of the letters are in good condition with typical folds. Several letters in pencil are somewhat difficult to read. Many letter include their original envelopes.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB