CSA Letter from Francis Fitzhugh, Charlottesville Light Artillery, Referencing the Battle of Cedar Creek

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 16, 2018

Cowan’s Fall American History: Premier Auction features over 200 lots including early photographs, documents, manuscripts, broadsides, flags, and more dating from the Revolutionary War period to the mid-20th Century, many representing important landmark moments in American history. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

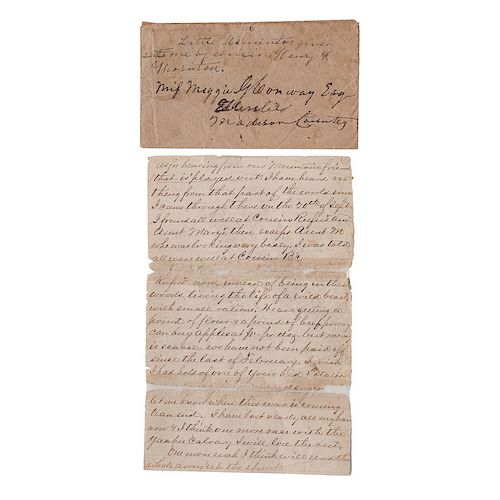

Fitzhugh, Francis "Frank" Conway. ALS, 18pp, 10 x 8 in, "Camp Near New Market, Va." October 27, 1864. Sent to his brother Catlett Conway Fitzhugh ("Dear Catlett"), though accompanied by a cover addressed to the woman he would later marry, Margaret Glassell Conway. Lengthy letter with vividly detailed descriptions of the Battle of Cedar Creek, as well as Winchester and Fisher's Hill.

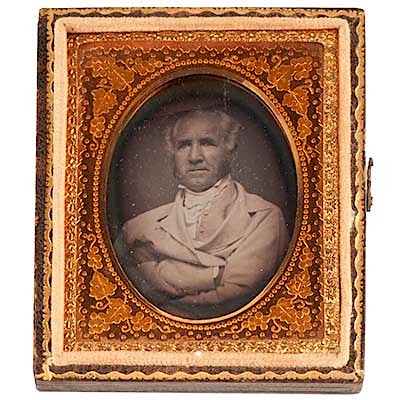

Frank Fitzhugh (1838-1910) of Barboursville, VA enlisted on March 15, 1862 as a private and mustered into the Charlottesville Light Artillery, also known as Carrington's Company. He was described at enlistment as having a "florid complexion" and was often in poor health. Fitzhugh was promptly hospitalized in July of 1862 for illness, then again the following May for wounds sustained to his left thigh at Chancellorsville, VA. He was hospitalized in July of 1863 in Charlottesville for unknown reasons, as well as in July of 1864 at Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond for typhoid fever. In addition to Chancellorsville, Fitzhugh saw action at Winchester, Spotsylvania Courthouse, and Cedar Creek, which he describes here. Remarkably, he survived the war and married Margaret in 1869. He remained engaged in the affairs of Confederate veterans and was a member of the UCV John Bowie Strange Camp in Charlottesville until his death in 1910.

To begin, Fitzhugh catches his brother up on some of the recent conflicts in which his unit was engaged: "At Winchester we were flanked on the left and had to fall back in some confusion. At Fisher's Hill. . . the whole Army broke. . . and scattered over the whole country, hundreds of the infantry throwing away their guns and going to the mountains. . . They seemed to have lost all confidence in their leader (Early) and in their own ability to resist successfully an attack from the overwhelming force of the enemy." Following their success, the Union army encamped north of Cedar Creek, where they "were engaged in fortifying their position."

The ensuing Battle of Cedar Creek, the culminating battle of the Valley Campaigns of 1864, was a tumultuous sequence of attacks and counterattacks. Despite Union fortifications, the early portion of the conflict seemed to favor the Confederacy, and Fitzhugh describes it as "one of the most brilliant of the war," led by Lieutenant General Jubal Early. He elaborates: "Our Infantry was put in motion with no canteens or anything to make noise, with orders to keep as silent as possible. Artillery ordered to be ready to march next morning at daybreak. . . next morning, just before light, they having got in line on the enemy's left and right flank, charged the enemy in their fortifications, driving them in great confusion. . . We captured 2,000 prisoners, 20 pieces of Artillery, many horses, ambulances, wagons, camps, clothing, cooking utensils, and in fact, everything about the camps. Drove from a strong position, made doubly stronger by fortifications, an army splendidly equipped at least three times our number, in complete chaos and confusion, covering the ground with their dead and wounded."

So assured of their victory, the Confederates stopped their offensive to reorganize and continue their plunder of vacated Union camps. However, by the afternoon, General Sheridan had managed to rally his troops to hold hold a new defensive line, promptly undoing any Confederate accomplishments and compelling them to fall back in panic. Fitzhugh recounts: "One of our pieces was left to fire a few shots while the others retreated. My piece had gone on; my curiosity led to remain behind. . . I found that Gordon's men had behaved most shamefully and cowardly, had broken in confusion and let the enemy in between our guns and the rest of our lines were scattered. . . I looked to my left and saw all our skirmishers running for dear life in the position we had just left. I saw advancing towards me the Old Star & Stripes."

Despite some "beautiful shots at the Yanks," they were undeterred, and Fitzhugh ultimately realized that he, too, must retreat, which he describes to his brother in harrowing detail: "I was with my gun in the middle of the road. It was nearly dark. I was nearly broke down. I saw the gun must be captured, so left the road and went through the field to the left. After getting some distance, ran with all my might parallel with pike, Yankees in shooting distance of me all the time. . . I do assure you, I made good time and got to that place little ahead of them. . . I had run five miles with my knapsack, etc. . . Next day, I could scarcely walk."

As he summarizes losses to his brother, Fitzhugh remains most galled by "shameful" behavior of his Southern comrades: "In killed and wounded the enemy's loss was much heavier than ours. . . [but] the stampede was a most shameful thing. No one can account for it. The attack was weak. . . If you can imagine a tremendous drove of cattle frightened sweeping with all speed over a vast plain as fair as the eye can reach, tramping under foot everything in front, running over and crushing each other under them as they go on, you can then have some idea of what I witnessed. . . when I saw our army break."

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB