CSA Captain Elliot Johnston, WIA Battle of Antietam, Wardate Letters, Incl. Detailed Correspondence about his Prosthetic Limb, Ca 1862-1864, Lot of 4Â

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

CSA Captain Elliot Johnston, WIA Battle of Antietam, Wardate Letters, Incl. Detailed Correspondence about his Prosthetic Limb, Ca 1862-1864, Lot of 4

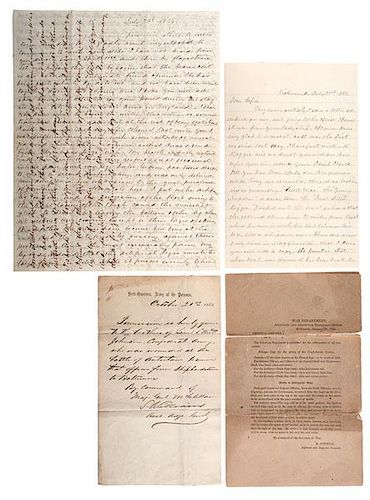

Lot of 4: 2 ALsS by Captain Elliot Johnston to his sister, Bessie Johnston Gresham (Richmond, July 21, 1862) and his mother (Baltimore, July 23, 1864); Union pass for Elliott Johnston, wounded at Antietam, to return home to Baltimore, signed by Brigadier General Seth Williams as Asst. Adj. General for George McClellan (October 21, 1862); and early Confederate War Department General Orders No. 4, issued January 24, 1862, from S. Cooper.

Approximately 70 percent of all Civil War wounds affected the limbs, and the treatment for those ailments (amputation) were almost as deadly as the minie ball. For the 30,000 Union soldiers and 40,000 Confederate soldiers who were lucky enough to survive dangerous surgeries and gangrene, many faced more pain in the process of recovery. The massive loss of limbs ignited a revolution in the improvement in the design and the mass production of artificial limbs. Prosthetic limbs offered the renewed chance of mobility, but sometimes, created more agony for recipients. Captain Elliot Johnston was one of the thousands of veterans to receive a prosthetic limb and experience the pains of recovery.

Elliot Johnston (1826-1901) was born in Baltimore, MD in 1826. Johnston was a planter on the Eastern Shore of Virginia before becoming a midshipman at the Naval Academy in Annapolis. He served in the United States Navy for seven years before resigning at the beginning of the Civil War. He was briefly imprisoned in Delaware at the beginning of hostilities due to his Confederate sympathies. By December 1861, he served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to General Richard B. Garnett. Garnett's Boonsboro report mentioned his “zeal, intelligence and bravery.” Johnston wrote to his sister Bessie, I wish I could tell you how beautifully our Confederacy works. Everyone is united. There is no bickering or quarreling. "Little Mac" the "Young Napoleon," or as we term, the "Great Ditch Digger," "pushed us to the wall" so hard that the rebound threw him 37 miles from Richmond where he is now with his tail between his legs, like a whipped cur....(Richmond, July 21, 1862). Despite his "zeal," General Stonewall Jackson relieved Johnston from command after the Battle of Kernstown. Garnett encouraged Johnston to seek another staff position. Taking his superior's advice, he volunteered to serve as an aide on General Richard S. Ewell’s staff. He served Ewell during the Battle of Gettysburg and received permission to use a flag of truce to retrieve Garnett’s body after Picket’s Charge. He was unable to recover it before the Confederates' retreated from Gettysburg. He was certain Garnett deliberately exposed himself because of Stonewall Jackson's charges relating to the Battle of Kernstown. Garnett's death “was but a question of time,” in his review.

Johnston was severely wounded during the battle of Antietam / Sharpsburg, resulting in the loss of his left leg. Union forces captured him on October 1, 1862 during Lee’s withdrawal from Maryland. Twenty days after his capture, his brothers carried a Union pass written by Asst. Adj. General Seth Williams permitting them to remove him from Shepardstown to Baltimore (Head Quarters, Army of the Potomac, October 21, 1862). After his exchange, the Confederate Army promoted him to captain. He served as Inspector for Leroy Stafford’s Louisiana Brigade in 1864, but pains from his leg plagued him. He wrote to his mother:

I was suffering very much with severe attacks of neuralgia and rheumatism. so much so that I was ordered by physicians to go South. My health is fully restored and I am quite well in every respect except occasional intense pain from my leg. Doctor Gibson has twice decided to make a second amputation, and was only deterred from doing so a few weeks since by the great prevalence of gangrene in the hospitals here. I put on the artificial leg too soon, and the congestion of the blood owing to the tight lacing of the thigh cause the muscle and flesh to draw up, leaving the bottom leg almost without any covering except a thin layer of skin. Besides this, the nerves have become bulbous at the ends and the artificial leg pressing against them proved at times the most excruciating pain. My leg is so reduced that the artificial leg is much too large for me in the front, while it presses severely behind, and the joints at the knee are not on the same axis with my knee joint. All these faults contribute to increase the pain and prevent me from being as active on my leg as I could wish, but still my walking is really remarkable. There is no one, if I except my Genl. Gordon, who has an English leg, who can approach me in the facility with which I get along. My leg chafes a good deal, and for this I cannot remain in the field in active service. Indeed, Hood is the only one who now attempts it, and he being in command of the Army of Tennessee, has conscientiousness that a captain on staff does not possess (July 23, 1864).

The Confederate Army agreed with Johnston's assumptions about his leg. By September 1864 the army declared him unfit for field duty. He retired to work for the Conscript Bureau. That winter he applied for a 4-month furlough to go to Europe in search of a better quality prosthesis for his amputated leg.

The early Confederate War Department General Orders No. 4 that accompanies the lot, issued January 24, 1862, outlines War Department regulations concerning Forage Caps (for the form know as the French Kepi) worn by officers and enlisted men in the Army of the Confederate States. The Order also covers the use of Havelock covers for sun & Oil-skin covers for rain & snow.

For a detailed look at the contents of the lot, go to: http://www.historybroker.com/collection/gresham/papers/4elliotta/elliotta.htm.

Bessie E. Johnston Gresham Collection of Confederate Manuscripts, Photographs, & Relics

Lots 89-115

Bessie E. Johnston Gresham was born in Baltimore, MD in 1848 in a home sympathetic to the Southern cause. Union forces imprisoned one of her brothers for aiding the South, and her brother Elliott was a Confederate officer who lost a leg at the battle of Antietam. She became an ardent and unreconstructed Confederate, and, in 1887, she married Thomas Baxter Gresham, a Confederate veteran from Macon, GA. She was actively involved in the Baltimore chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and amassed a notable collection of Confederate manuscripts, photographs, and relics at the Gresham home at 815 Park Avenue in Baltimore. Most of her items were left to the Museum of the Confederacy, the Maryland Historical Society, and other institutions. This important collection of Johnston-Gresham family and Confederate-related material, was passed down through Bessie Johnston Gresham’s step-son, Leroy Gresham, before it was acquired by the consignor.

The collection features over 50 CDVs accumulated by Bessie and Thomas Gresham, offered as Lots 89-100. Some are wardate, and others were apparently acquired in Baltimore soon after the war's end. Some CDVs include patriotic inscriptions and quotations written by Bessie on reverse, which showcase her deep feeling of love and devotion to the Southern Cause.

In a June 1862 letter delivered through the Union blockade, Elliott Johnston, serving as aide-de-camp to CSA General Richard B. Garnett, mentioned collecting photos of CSA generals for his then 14-year-old sister Bessie.

In a 1926 issue of Confederate Veteran magazine, a memorial essay described Bessie's girlhood during the war:

"One of her brothers, who was on General Ewell’s staff, suffered the loss of a leg at the battle of Sharpsburg; her two other brothers were active Southern sympathizers and were under constant surveillance by Federal authorities for giving all possible aid to the Confederacy; her home was a center from which radiated help. “

"Reared in this atmosphere of deep love for our ‘cause,’ she became an ardent and unreconstructed Confederate. "

During her girlhood, Bessie was acquainted with many Southern generals and received from them letters, photographs, and autographs, as well as a number of gifts.Very good excluding the special order, it has some separation at one of the folds. The Union pass has some tape reinforcing it on the reverse.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB