Confederate Presentation Civil War Swords and Diary of Capt. Daniel R. Hundley, 31st Alabama Infy., CSA

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Apr 26, 2016 - Apr 28, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

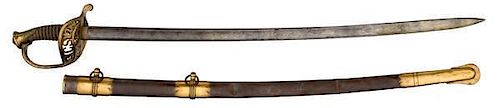

This sword was presented to Captain Hundley by his mother on August 1861. Presentation information is on the pommel of the sword.

32" blade with etched panels of military motifs; one of the panels had the "US" taken out and marked with Confederate States and dated 1861. Shagreen and gilt brass wire wrapped handle. Engraved on the backside of pommel is a presentation inscription "Presented to Captain D.R. Hundley CSA by his mother August 1, 1861." On the brass knuckle bow the US was also cut out and replaced with CS. German proof on the ricasso. Metal scabbard with brass bands and carrying rings. On the throat of the scabbard is a banner marked Horstman and Sons maker Philadelphia.

Plus a 1902-style Army Officer's sword, 30" blade with etched panels of military motifs. The name is etched in a panel: Bryan R. Hundley. Black handle, nickel-plated guard with nickel plated scabbard. The 1902 sword is in excellent condition. This sword is Vietnam War era.

Daniel Robinson Hundley (1832-1899) was born to John Henderson Hundley and Malinda Robinson, plantation and slave owners in Madison County, Alabama. Daniel received his law degree from Harvard in 1853. He married a first cousin, Mary Ann ("Nannie") Hundley (1834-1913) about 1857. Three children came rapidly, two sons and a daughter, by 1859. The family moved to Chicago where Daniel maintained a small farm and tried to find work as a writer. In 1860 he published Social Relations in our Southern States (New York: Henry Price), an analysis of the antebellum social and political climate in slave states, often cited as a major reference.

The family struggled financially, so when hostilities erupted, in April 1861, he returned to Alabama and was commissioned as Colonel in the 31st Alabama Regiment. He was wounded at the Battle of Port Gibson (May 1863), and taken prisoner at Big Shanty, GA (June 15, 1864). Taken to the officer's prison at Johnson's Island, he attempted an escape in Jan. 1865, but was quickly recaptured. The diary he kept while incarcerated was taken from him at his recapture.

The 31st Alabama was organized in March 1862 at Talladega with men from the surrounding counties. It moved to Tennessee, first to Chattanooga, then to Knoxville. It took part in several fights, Cumberland Gap and Tazewell before joining General Edmund Smith's Kentucky Campaign. It was then moved to General Edward Tracy's Department of the Mississippi. It was engaged in the defenses of Port Gibson and Vicksburg, where it was captured and quickly exchanged. It was then moved to the Army of Tennessee, following John Bell Hood's forces. Of the 1100 men serving in the unit, by Jan. 1865, only 180 were fit for duty and fewer than 100 surrendered in April.

Hundley was released from Johnson's Island in July 1865, and returned to his home, Thorn Hill near Mooresville, to begin a law practice. Nearly a decade later, in 1874, he received a letter from a man in New York who had located the diary and subsequently returned it to him. Hundley filled in a few blanks from the last months of his incarceration, and published the diary as "Prison Echoes of the Great Rebellion" that same year. It was his last venture into writing. He spent the remainder of his days quietly, practicing law and raising a family which grew by a number of children. All together, Daniel and Mary Ann had 11 children, although three died in infancy: Edwin, Margaret, Cecil, Edith, Oscar, Warren, Mary, John, Elisha, Lucy, and Anne. (Oscar, John, and Elisha all married.)

We have not been able to locate Bryan Hundley. Consignor relates that he purchased this sword from Bryan Hundley (a direct descendant of the original Bryan Hundley). Daniel had four siblings: Orville (who became a state senator and Republican delegate), John, William, and Mary. Bryan could be a grandson of Daniel or any of the three brothers (or part of Mary Ann's family line). Presumably, with the 1902 date, this sword represents SpanAm service.

A diary accompanies this lot. Although not one of Hundley's, it was written by a resident of Mooresville, Alabama. The writer, however was a woman, and a bit older. The 8 x 10 in. half-leather over marbled paper book has 144 pages filled in. It begins on 19 Oct. 1856. It is relatively complete until August of 1857, mostly with news about the community (who is ill, who died) and church activities. The rest is spotty until 10 July 1859. On Dec. 31, 1857 she describes the death of her sons: "Since the last entry... I have passed through the deep waters of affliction, my dear children Henry and Robert have passed away from the earth... Henry died on the 30th of August of typhoid fever after an illness of two weeks, his age seventeen years and five months. Robert was very ill at the same time with the same fever....his spirit went back to him who gave it on the morning of Dec. 8th at a little past 6 o'clock, at the age of sixteen years and nine months..." A week later, she laments: "I can hardly realize that I am the same being I was six months ago. Then I was the proud happy mother, now my heart and home is bereft." (Not only was Hundley not a mother, he was born in 1832, and could not have had 17 and 16-year-old sons in 1857, being only 15 or so himself.) Unfortunately, the only identification is on the rear fep, with have "Mooresville, Alabama, Limestone County" written on it. This was Hundley's hometown, so he surely knew these neighbors. They might have been relatives.

The first 72 pages cover the antebellum period. In the middle, she jumps from July 1859 to 19 Dec. 1863. Coverage in this section is mostly continuous until 5 Nov. 1864 (58 pages), but the last 14 or so pages are mixed. There are some early items (1853-1859), many histories, or religious extracts, in the last dozen pages, but if there were three or four blank lines at the bottom of the page, she continued the diary there.

This second section is very different. It gives the "home front" view of the war, and, at that, from an interesting perspective. Northern Alabama was strongly sympathetic to the Union. Ormsby Mitchel had a relatively easy time invading the area in the spring of 1862. Holding the area, however, was a bit more difficult, since it was deeply divided between Union and Secessionist sympathizers. In addition, much of the region's economic activity focused north. The writer of this journal seems to be sympathetic to the Union, although she mentions several times that a number of their slaves have left or been taken by the army, or that soldiers were going from plantation to plantation running the slaves off (freeing them). A few months after the death of her sons, she went to visit family - sisters, mother. Her father had died about the same time as her sons, so she visited his grave, also. She spent several weeks in Aurora, Illinois, making a trip into Chicago to shop. At a later point, she mentions an Ohio unit that is camping in the area, headed by a Captain from Zanesville. She and the Captain spent several evenings catching up on mutual acquaintances.

This diary gives a view of the hardships of a war zone. Foraging soldiers taking their corn, forage, meat from the smokehouses. And in Northern Alabama, there were waves of both Confederate and Union forces, needing food for themselves and their animals. She describes hearing cannonading from Decatur and Athens. Interestingly, "official" histories place the Battle of Decatur on Oct. 26-29, 1864, as part of Hood's Tennessee campaign. However, there is activity for months before this. Something is happening in Decatur at least every week - more troops coming in, Confederate raiders making a run at the Union forces, sporadic skirmishing, etc. For most of the year, the residents of the Mooresville-Huntsville area cannot cross the river to Decatur. The residents personally appeal to General Dodge, but he will not guarantee them protection from the soldiers under his command. He only assures them that they won't take anything "except demanded by military necessity." Guess that covers just about anything.

She mentions each unit as it comes and goes, and even where it camps. Jan. 25th: 80th Ohio & 7th Iowa; 28th: 93rd Illinois & 10th Iowa. On May 21st, the 9th Ohio came in, and set up camp on the hill near the graveyard. (This was the unit headed by her old friend from Zanesville, where she lived 26 years before.) The citizens are intensely interested in war news. She notes: "We get intelligence of affairs from the Federal party only and we know not which portion of the rumors can be credited." (Note, this was true of the men in uniform, also. Rumors flowed freely.) At one point the 16th AC was ordered to Chattanooga, and she notes that it took them 6 hours to get through town. Shortly after, she observes: "our town has been literally alive with soldiers."

She is (still) sympathetic to humanity in general. She seems to retain a northerner's attitude toward the climate: [July 1] "The weather almost suffocating. If we at home, sheltered from the rays of a summer sun can hardly exist, what of the suffering of the poor soldiers...." On the 25th, they get rumors that Atlanta was captured by Sherman. A bit premature, but after Atlanta did fall, it took a full two weeks for the news to reach Mooresville. She expresses great interest in the Democratic Convention in Chicago, hoping they could get a candidate who would end the war.

She missed nothing. On Sept. 6: "Six trains passed down loaded mostly with contrabands going we suppose to Tennessee to repair bridges and so forth"(that Wheeler had been burning as he went). On the 10th they get reports that Grant and Sherman had both been defeated. Not quite, since Atlanta fell the week before. Fighting was also increasing around Athens, and Union soldiers were putting up breastworks throughout the fields around town.

Union soldiers borrowed her buggy on a number of occasions. One time she notes: "Our buggy returned. We know nothing definite with regard to the business in which it has been engaged but suppose from some items gathered it has been used for transportation of a female spy." Much more. Although there are numerous views of soldiers, homefront diaries, especially from literate women, are much more rare. We are sure there is much to be learned from this account, possibly even the identity of the writer.Brass has been polished and began to age nicely. Handle is in good condition complete intact with some scuffs. Blade is a dark grey to brown. Panels are visible. Scabbard has a four dents, two on each side. Brass is good.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB