Civil War Sutler's Clerk Archive, Letters Written by Frederick P. Ranney, 40th New York Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1867

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

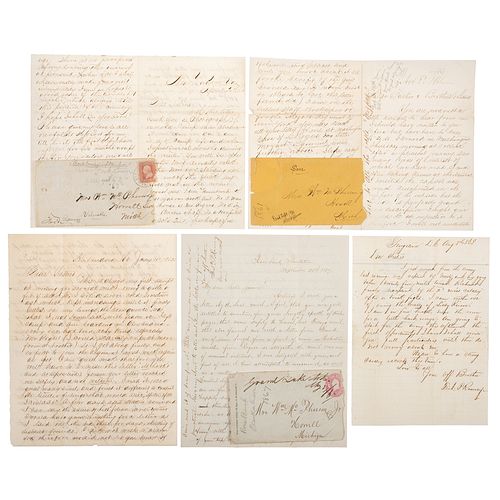

Civil War Sutler's Clerk Archive, Letters Written by Frederick P. Ranney, 40th New York Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1867

Lot of 15 letters by Frederick Packard Ranney (1844-1884), a sutler’s clerk for the 40th New York Infantry, written to his family, November 1861-September 1867. A bookkeeper from Monroe, New York, Ranney joined the 40th New York Infantry, also known as the Mozart Regiment, in the fall of 1861. His primary correspondent is his older sister Jennie M. Ranney McPherson (1836-1905), who married William McPherson, Jr. (1834-1915), a Scottish lumber magnate and prominent early settler of Powell, Michigan. In his letters, Ranney provides his family with details of his Civil War service, including a dramatic account of the Battle of Chancellorsville, a female solider in disguise, and his experience as a Confederate prisoner, as well as his business ventures during Reconstruction in the western United States.

The role of sutler was often filled by a civilian businessman who typically identified himself with a particular regiment. Sutlers provided goods and camp fare, including items that were not readily available to the soldiers, and accompanied the regiment from camp to camp. Wares could range from writing materials to ID disks, and from clothing items to desirable foodstuffs the army did not provide. The sutler of the 40th New York Infantry was “C. Rogers,” who joined the regiment at Fort Runyon. Known for his swindling and avarice, Rogers purportedly fixed the prices of his goods and fraudulently extended lines of credit to impecunious soldiers, abruptly calling in debts directly from the paymaster. According to regimental accounts, hostilities built between Rogers and the men, who began to employ counterfeit orders for large quantities of product to “steal” hundreds of dollars’ worth of goods from him. Ranney’s name is absent from these records, but his writing reveals considerable mistrust, even fear, of the soldiers he serves, tying his loyalties firmly to Rogers.

His earlier letters in the archive were written from Alexandria, Virginia, where the Mozart Regiment performed defensive duties for Washington, DC as an attachment of the Army of the Potomac. Ranney describes a grand review of the army and popular sights he visited in the city: “I went to a grand review of our Division, ‘General [Heintzelman’s].’ There was about ten thousand troops there making a grand sight, the ground upon which it took place was within sight of Mt. Vernon and consequently all the more interesting. . . I saw the Declaration of Independence (original one). . . My next visit was on ‘old Abe,’ he was not receiving visitors at that hour of the day or I might have gone in and made a call.”

On April 20, 1862, during the Siege of Yorktown, Ranney writes of close encounters with Confederate sharpshooters whilst performing his regimental duties: “Yesterday, I made a visit to camp. Went out and laid down by a fence and watched the rebels at work, at only about ¾ of a mile distant. Whenever a shell was thrown my head sunk down some, so as to let it go over. . . Sharpshooters are at work and whenever a man makes his appearance, death follows frequently.” Specifically, as he writes in July 1862, his position entails having “the whole hand of running the store, of settling all accounts, and cashier generally. . . our sales are from three to six hundred dollars daily and as Mr. Rogers is frequently away two to three weeks, they amount to no inconsiderable sum. I frequently feel alarmed to think of the many evil characters around me and how little the[y] would care for me were they sure of their reward. I always go around with a six barrel pocket piece and think I should use, if occasion required. My salary is $40.”

Despite his animosity towards the enlisted men he serves, Ranney holds great esteem for the Union Army’s generals, defending General George McClellan from the “disgraceful and cowardly” speech delivered by Michigan Senator Zachariah Chandler in Jackson, Mississippi on July 6, 1862, a scathing reproof of McClellan’s failure to capture Richmond: “The idea of his taking the liberty to speak of the man to whom the country owes so much. The army adores him and I think he will yet able to show the world the true character of the man.” Later, in May of 1863, Ranney defends General Joseph Hooker’s efforts following the Union defeat at Chancellorsville: “Great confidence was expressed in Gen. Hooker’s ability and I think all feel certain that one week’s expedition would bring us within the vicinity of Richmond.” Ranney describes the battle in further detail, writing, “The Confederates finding out our successful maneuver sent their entire army with the exception of one Brigade to oppose Hooker on the right, when Gen’l Sedgwick crossed the river into the city and made a desperate charge on the main fortification. . . Our troops having gained the entrance to the Fort. . . my patriotic feelings were aroused to the highest pitch, as the colors were waved from the highest point of the fortification. . . Wednesday Longstreet came with quite extensive reinforcements form Richmond, the number was overpowering to Sedgwick and he was forced to retire. . after regaining the ground that the rebels had lost. . . attack reinforcements were sent to Lee who was opposing Hooker on the right. Against the combined forces of Gen’l Lee, Longstreet, and Jackson, he too was forced to retire.”

In August, the Mozart Regiment was assigned to duty at Rappahanock, where Ranney was briefly taken prisoner by Confederate troops. He writes to his sisters on August 8, 1863, describing the experience: “I. . . was captured by Mosby and his gang, taken twenty five miles toward Richmond, finally recaptured by the 2 Mass’ Cavalry after a brisk fight. I came within one mile of seeing the walls of Libby Prison.” The next major engagements for Ranney’s regiment were in the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House the following spring, after which Ranney recounts a curious incident with a female soldier in disguise, writing on May 19, 1864 that “a young Volunteer was brought in to have his wounds dressed, preparatory to being sent to the rear. Imagine the surprise of the assembled people when instead of a boy, a young lady’s wounds were to be dressed.”

After participating in the Siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox Campaign, the 40th New York Infantry was mustered out of service on June 27, 1865. Ranney, in search of employment, traveled West after the war. On December 18, 1865, he writes of his reception as a Northerner by former Confederate soldiers in Arkansas, noting that they “had no particular love for the Yankee race in general, and gave us unmistakable signs of their hatred in looks, if not actions.” By June of 1867, Ranney had settled in Arkansas as a cotton planter, albeit an unsuccessful one. He tells Jennie that Rose Bank, his plantation, “has been on the whole an unfortunate investment from the beginning. . . I think there must be a curse on the whole country.” Ultimately, his career as planter failed, and Ranney moved on to Kansas City, Missouri, where he married and had two daughters. - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB

![[MEDICAL HISTORY] Craig Gutta-Percha Microscope Base](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/m/2904/29046456.jpeg?t=1Ttr6w)

![[CIVIL WAR] William T. Sherman CDV Portrait](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/m/3259/32590994.jpeg?t=1UVtrf)