Civil War Medic & Drummer, Harvey A. Chapman, 121st Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Manuscript Archive

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 21, 2014 - Nov 22, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Civil War Medic & Drummer, Harvey A. Chapman, 121st Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Manuscript Archive

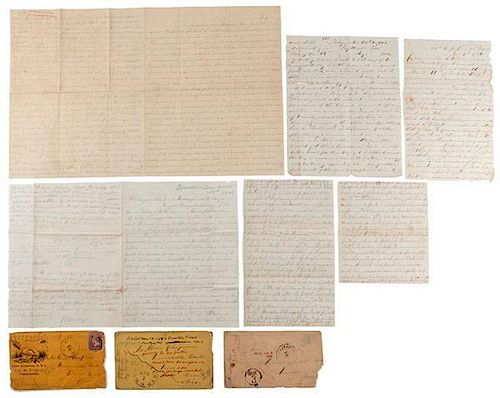

Lot of 77 war-date letters (including 37 soldier’s letters), August 3, 1862-September 27, 1865, with the majority of Chapman’s letters accompanied by the original mailing envelope; pocket diary spanning January 1, 1864 - May 18, 1864. Archival material comes with typed transcriptions of letters and journal as well as a copy of the 2006 book in which the manuscripts were published, entitled The Man Who Carried a Drum: 108 War Letters and Love Letters of a Civil War Medic, by David Wesley Chapman.

Harvey Amasa Chapman was a farmer from Union County, OH, who enlisted in the Union Army on August 16, 1862. Large numbers of Ohioans enlisted at this time to help repel the advancing Confederate Army which, under the leadership of General Braxton Bragg, was marching north nearly unimpeded through Kentucky and threatening to cross into Ohio. On September 11, 1862, Chapman mustered into service at Camp Delaware with “I” Co. of the Ohio 121st Infantry. The men in his regiment, consisting primarily of enlistees from Ohio’s Delaware, Knox, Union, Hardin, Logan, and Morrow Counties, were to serve three-year enlistments.

At the time of his enlistment Chapman was a 37 year-old widow and father to two young sons, Darius and Fred. He left his sons in Central Ohio in the care of his brother Alonzo and his sister Annis, both of whom figure prominently in this correspondence. A religious man, Chapman enlisted as a musician and acted as an infantry drummer as well as a medic during his enlistment. In this way he could serve his country without carrying a weapon or engaging directly in violence, something that may have been objectionable to a man of his deep conviction.

The letters in the archive are very personal in nature. Correspondents are friends and family members of Harvey Chapman primarily located in Ohio. The overall perspective represented in the letters is that of a typical Central Ohio farming family of which Harvey Chapman remained a central figure even after his deployment. Yet a great deal of information related to period politics, social conditions, army life, hardship, and significant military engagements can be found here as well.

Harvey’s first letter home, dated September 17, 1862, is written from Cincinnati and is addressed to his parents…I was disappointed in getting a furlow to come home. Our Col. refused to issue any permit of the kind whatever./We had marching orders on Wednsday at 4 P.M. for this place. We went aboard the cars at 6 O’Clock in the eve. & after riding all night arrived here at 6 the next morning. The cty was all excitement – troops poreing in at allmost every hour./16 000 armed soldiers crost the Ohio river into K.Y. the day we arived. There are now 50 000 soldiers incampt within 8 ms of Covington garding the railroad and other roads leading to this place.

Nearly every letter written by Harvey includes an exhortation to write more frequently. Like all soldiers, Harvey is hungry for news and letters from home. Mail service was frequently interrupted because of the war and could be slow or even non-existent. It is clear Harvey is unsure at times whether his family is writing to him, and he pleads with them to be prompt with their responses to his letters. On November 29, 1862, Harvey writes from Perryville, KY: As for war news & army movements, we know nothing, only what we see. I have written to you for information, but do not get any, even in regard to home affairs. I have been in this house 27 days & have written home three times & received no answer. If you have written & I have not received, you are excuseable./But you have not written, you are realy hard hearted. You cannot imagine how anxious I am to hear from home, from Father & Mother & my children. How you ar all getting along.

Harvey had good reason to be anxious for news from home. Whilst his family members were not in direct danger from the war itself, life was difficult on the home front and posed its own unique challenges. Correspondence details the hardships faced by Harvey’s family while he was away, including maintaining his farm, raising his boys, dealing with cold and drought, managing money, and, most frightening, enduring outbreaks of sickness. These letters are filled with descriptions of both Harvey’s health and that of his family, neighbors, and friends. Central Ohio was plagued over the war years by outbreaks of scarlet fever, diphtheria, consumption, smallpox, diarrhea, and whooping cough. Life was difficult and fragile not just for the soldiers, but for the settlers as well. On April 2, 1864, Harvey’s brother Alonzo writes to him about the suffering in their community: Your letter gave us the greatful information of your good health…. There has ben some sickness here and some have died…. Spencer Holycross is dead….Doc. Hayne is very sick. Jona Marshall has lost two daughters with Erysipylis. Jona’s oldest son George Marshall’s wife is in a bad state of health – is rather insane./We are in common health, the most of us. My Clara had a chill today. Had had one before, but she has gotten over it and is around – as perk as usual. Hope she won’t have it long…I am mistaken. Jona’s girls died of Diptheria. Your boys are as well as common.

Harvey’s health would be a constant sort of anxiety for his family as well. Harvey dealt with chronic bouts of diarrhea, and painful rheumatism that was exacerbated by exposure to cold, damp weather and long marches. On May 16, 1863, Harvey writes to his sister Annis from Camp near Franklin, TN: You desire to know the worst condition of my health. Well, my general health is good, but I am very muched of a cripple on account of rheumatism. If the Rebs were to make a dash on us and put us to flight, I should have to surrender, for I could not shoot with my drum sticks, nor run with my legs./ I can walk about camp where I pleas, but it is with short slowe step. My limbs do not swell like some others, but I have constant acheing pain in my hip or the small of my back, and sometimes up in the boane of my left thy frequently aches. I go to get up, a stitch will ketch me in the back that I have to make the seckond & often the thurd effort befor I can get up./ But I doant get discouraged. I think I shall get better and have strong faith that this war will end by suppression so that we shall return home before an other winter.

Harvey’s faith that the war would end in the near term was a common sentiment, but one that would not come to fruition. As the war raged on, both Harvey and his correspondents write of their desire for news from the battlefront and share the information they do have. The letters demonstrate that little information on the wider war effort was getting to the troops, and that rumors circulating in the north about troop movements and battles were often grossly inaccurate. Harvey’s own first-hand observations on the war, however, provide clear and vivid accounts of the violence and extreme difficulty endured by soldiers.

On September 27, 1863, Harvey writes to his sister Annis about his experience at the Battle of Chickamauga, which with more than 34,000 combined casualties was the deadliest battle in the Civil War besides Gettysburg: Our Regt. fought on the right wing. You must not ask, nor expect me to discribe the sum of action, for I caunt do it under presant circumstances, for I am two near woarn out with fatigue. But sufise it to say that I was in the whole engagement, from the time comensed, which was about 12 A.M., and continued until 4 P.M. I had charge of apart of our Ambulance Chorps, and carried one end of a Lyter, to carry off 15 wounded men./We dashed up under the fire of the enemys fire and pick up the poor wounded boys & then run, takeing the best advantage of the ground to skrean us from the ball we could. It seamed to me the balls passed evry place except were the space I occupied, but I escaped on injured. Describing his mindset during battle Harvey goes on to say that my mind was onusually composed and my nerves were steddy./ My trust was in the Lord & I felt myself wonderfully supported y his divine influence and when the cannon thunderd and the shells burst & bulets whized around me, my nerves did not relax nor niether was my hope in my Savir wavering and feal as tho I should be hurt.

During his time with the 121st Infantry, Harvey Chapman witnessed some of the major engagements of the Civil War. Letters in the collection detail his experiences at the Battles of Perryville, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Lookout Mountain, Missionary Ridge, and then as part of General Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, in which his regiment participated in engagements at Buzzard Roost and Tunnel Hill. The 121st then pursued Confederate General Joseph Johnson throughout Georgia until ultimately participating in the Siege of Atlanta.

As a medic and particularly as a drummer, Harvey faced fewer immediate mortal threats than his fellow enlistees. Harvey was well aware of this fact. On March 21, 1864, Harvey advises his brother Alonzo to tell a friend to get him a fife & lern to play. He may be drafted into this war & a musition can get along much easyer than a common soldier & for which reason it is well worth his while to lern to blow the fife. The letters contain other interesting observations on army musicians such as this tidbit contained in a June 1863 letter to Annis: I am glad you have received the things I sent to the Valley. The bundle consisted of one blue camp blanket, one white blanket, one read shirt, an oald blouse with some trinkets in the pockets, amongue which was a little ball of read strips of flannel./ It may be a curiosity to you to know what they ware used for. The musitions in time of battle ar required to tie such as one of those strips round his left arm to disignate him as a non-Combatent. And if captured, will be treated as such, or expects to be. Our Chorpse of musitions wore those strips in battle at Perryville, K.Y.

Another recurrent theme found in the letters is expansive discussion on politics, particularly the Copperheads, a vocal group of Democrats who opposed the Civil War and wanted an immediate peace settlement with the Confederates. Led by two Democratic congressmen from Ohio, this movement was exceptionally strong in Ohio and elicited sheer outrage from numerous letter writers. In June 1863 Alonzo describes the Copperheads as wicked demagogues who desire to inagurate civil war in our state. C.P. Perkins, a friend of Harvey’s, says this of the Copperheads in 1863: There is a party here in the North, to say it plainly the regular old mean democrats party are raising the cry of peace, and magnifying every error and mistake of the present administration, and sympathizing with the rebels and doing every thing they can to weaken public confidence in our government, all for political purposes. Pretending to be devoted to the union, their purpose no doubt is to take possession of the government and then acknowledge independence of the Southern Confederacy.

Additional items of local and national interest such as this are found throughout the letters, including sentiments on slavery, Lincoln, John Hunt Morgan and Morgan’s Raid, the role of women, a potential draft, the competency of the Union military command, the railroad, and the Universalist church. Pervasive throughout all the letters are references to God, and the deep and abiding faith that sustains both Harvey and his friends and family on the home front.

The pocket diary accompanying the letters represents a period of just under five months, from January 1, 1864, through May 18, 1864. Harvey spent most of this time period in winter camp in northern Georgia prior to joining Sherman’s campaign in the summer of 1864. While Harvey mentions other diaries he kept during the war, this appears to be the only one to have survived. Much like the letters he wrote, the diary is full of daily camp life and ritual: drilling, making dinner, rations, checking for mail, cutting wood. We learn that Harvey shaved soldiers to make extra money to send home and wrote letters for those soldiers who were unable to do so themselves. Harvey writes in his diary of his health and the daily weather conditions as on this entry from January 1864. 14th. Thursday morning. A very white & heavy frost, a very thickfog, and damp breakfast over [?] call made & gards mouted – a light camp gard on today Beef on boiling for dinner. Doant feel feel very well today did not sleep much last night Made a dore to our shanty made morter and dobed the cracks makes it much warmmer/Dress parade is over, time to get supper No letters from home today Yet hope I may get one this eve male.

Occasionally, a diary entry provides a more detailed description of an event, such as this entry from May 8, 1864: 8th. Sunday morning. Orders to march at 6 O'Clock AM. No dobt, but we will be in a hard fight before night. The designe is to attack the rebs at Buzzard's Roost today at four ms distance from hear./May the Lord have mercy on us & prosper the Cause. Liberty & wrighteousness./10 O'Clock A.M. Still hear on T. Hill. There is a goodeal of musket fireing in front on the left & in the Centre, we ar expecting to be ordered out in a fiew minits./12 O'Clock A.M. The 121st Regt. Has just received orders to march to the front as skirmishers to relieve the 108th Ill., who were sent out this morning. I was ordered to take charge of a squad of convalesents & report them back to the Commander of the 2nd Dav Ambulance Commander, to be sent to the Hospt. Had to march them one mild & a half & have done so & returned to wait for further orders from the Regimental Surgeon Dr. Hill Commanding musitions as Ambulance Corps./Two hours later: can hear our Regt skirmishing very distinctly./ Was ordered up to the Regt at dark, found them thre milds in the front, within one mild of Buzzard's Roost, where we expect a warm engagement with the rebs tomorrow.

In conjunction with his letters, the diary demonstrates that Harvey was a dedicated soldier, a good father, and a deeply religious man. Like the tens of thousands of men fighting for the Union cause, Harvey believed strongly in his mission and in the certainty that the North would prevail.

Provenance: Descended Directly in the Family of Harvey A. ChapmanHarvey’s small pocket diary is in good condition, though it is no longer bound. Overall the condition of the letters is good as well with limited amounts of discoloration and tearing. Most letters are clearly legible, though some have print that is faded and difficult to read. However, the accompanying transcriptions and book publication of the letters alleviate the difficulty in reading the written text. Purchaser should note that the book does contain pre- and post-war letters which are not included as part of this manuscript consignment.Condition

The original letters are printed on a variety of sizes and types of paper with a few letters being written on official 121st Regimental stationery. The majority of letters from Harvey also come with the original mailing envelope. Letters and envelopes are marked with some non-period colored ink. Nearly every letter does have a handwritten green number on it that signifies the order of the letters, and some letters contain discreet handwritten annotations in red ink. Annotations indicate things such as when the letter was written and to whom. The envelopes, paired with the letters, also bear matching corresponding green numbers and red ink notations. Despite the ink additions, the letters retain excellent character and quality. The archive would be a superb addition to a collector’s or institution’s Civil War era collections. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB