Civil War Letters of Sergeant Mathew Halpin, Co. K, 22nd New York Infantry, with Fascinating Battle of Fredericksburg Content

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Civil War Letters of Sergeant Mathew Halpin, Co. K, 22nd New York Infantry, with Fascinating Battle of Fredericksburg Content

Lot of 8 letters written by Sergeant Mathew Halpin, Co. K, 22nd New York Infantry to his friend Albert A. Fletcher (ca 1835-1907), a farmer in Bridport, Vermont. Halpin (ca 1843-1909) emigrated from Ireland in 1847 and settled in Vermont. Compelled to fight for his new country in the Civil War, he enlisted at Port Henry, New York in the spring of 1861 as a private with the 22nd New York Infantry. He attained the rank of sergeant on August 31, 1862 and was engaged at key battles including Gainesville, Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. In his letters to Fletcher, Halpin records his experiences as a soldier, describing mob riots at camp, a grisly train accident in Northern Virginia, and, most notably, key maneuvers by the Union army at the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 12-15, 1862.

Halpin writes two letters from Albany, New York, where his regiment apparently boarded until their dispatch to Washington, DC in defense of the city. On April 12, 1861, he tells of great “noise and excitement…among the troops,” possibly caused by a group of antiwar “Copperhead” protesters. In the middle of the night, “we were aroused by the mob, a set of young men that go around this city making disturbances. We immediately got up and found it necessary to place a guard at four different entrenches of this building…the mob retreated and did not disturb us more that night…next morning the[y] returned and commenced throwing stones at the guard when one of them drew his revolver and fired three timing missing twice and killing one man. That night his comrades came back, probably with the intentions of revenging him, and snatching a musket of one of the guards thrust the bayonet at his breast, but before he could do any damage he [was] knocked down and [was] pinned to the ground by the bayonet.” A larger, deadlier Copperhead demonstration took place just a week later in Baltimore, Maryland.

By July, Halpin and his regiment have made their way to Washington, attached to Keye’s Brigade, Division of the Potomac. Spirits were high when they left New York, and friends, family, and other well-wishers left the soldiers with “bottle[s] of liquor in abundance.” Halpin confides that “one poor cuss who got a bottle jumped overboard while the boat was in motion and took to swimming to shore but was quickly picked up in a small boat and brought back a prisoner. I stood guard…with orders not to let anyone pass in or out. Several came and asked but were refused…about 11 a drunken man came and tried to pass. I refused him. The next I knew he caught hold of my musket and tried to wrench it from me but fell…after a short struggle when he got on his feet [and] came right up full determined to gain possession of my gun when my partner punched him in the side of the head with the breach of his gun and knocked him over.” After a summer and early fall of guard duty at Arlington and Upton’s Hill, Halpin and the 22nd New York took up winter camp for 1861 at Upton’s Hill.

Spring of 1862 brought new weaponry (“our whole brigade has got new rifles. They are death at 500 yds”) and plenty of mud, but little action besides drills, guard duty, and skirmishes: “I don't see why they keep such a large army here on the banks of Potomac doing nothing but picket duty” (February 12, 1862). In March, Halpin decides to visit the battlefield at Manassas Junction, the site of the demoralizing First Battle of Bull Run. He tells Fletcher of the somber experience, writing in part, “I started at daylight and got on the battle ground. . . it stretches for six or eight miles. . . and is covered most part by [second] growth pine. But few of our men were buried and those [that were] only got the name of it. . . the bones sticking up out of the graves. A company of the Brooklyn 14th were out burying the bones of their dead companions. The citizens say they were all buried, but the Louisiana Tigers rooted them up. It was a hard sight.”

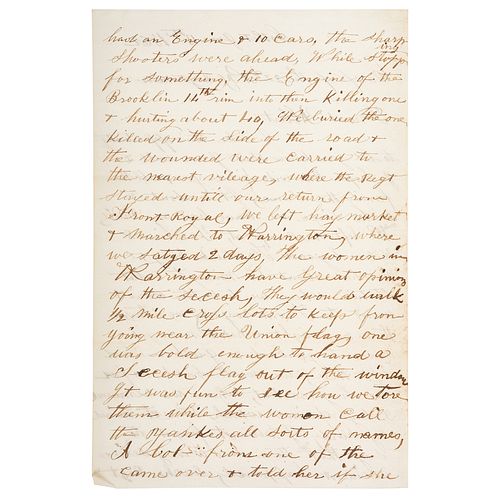

For the majority of June that year, Halpin and his regiment were engaged in operations against Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and on June 13, 1862, he tells Fletcher of a horrifically ill-fated cat and mouse game with the Confederate General: “…we left our camp at Fairview, 8 miles beyond Fredericksburg & marched about 50 miles to Catlet station where we took the cars & went to Front Royal. We stayed there overnight…[but] got orders to go back as [Stonewall] Jackson had left there…there was a very serious accident…each regt had an engine & 10 cars. The sharp shooters were ahead. While stopping for something the engine of the Brooklyn 14th ran into them killing one & hurting about 40. We buried the one killed on the side of the road & the wounded were carried to the nearest village where the Regt. stayed until our return from Front Royal.”

Halpin’s next letter comes just days after a devastating Confederate victory at the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 12-15, 1862. He gives Fletcher a brief summary of the engagement, noting key strategic elements – and coincidentally advantageous weather conditions - that helped reduce the number of casualties from his regiment: “What do you think of our dance across the Rappahannock? We had a pretty rough time of it there. . . Doubleday's division was on the left. We lay about 4 miles below Fredericksburg. The hardest fighting was in the centre and right. The left was one continual roar of artillery. Our fellows worked hard to silence the Reb's batteries, but they fired with terrible effect on our infantry. We were drawn up in line of battle on a large flat, a good mark for rebel artillery to play on. Our Regt. was in advance so that most of the shells went over our heads. Towards night on the 2d day they fired grape and canister and hit 4 out of our Regt. None were wounded seriously. The retreat back across the river was one of the best conducted movements of the war. A heavy wind blowing in the direction of the river favored our movement. We knew nothing of where they we were going…the Rebels never suspected our leaving until next morning when they see the plain vacated that was the night before covered with men. There is great speculation in the papers as to what this movement is. Some call it strategy, but here we call it another grand skedaddle...We were on one side of the river, the Rebs on the other…it froze hard.”

Also included are the original transmittal covers, including one example free franked by New York Congressman James Harper Graham (1812-1881).Creasing as expected, with areas of smudged ink and foxing.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB

![[MEDICAL HISTORY] Craig Gutta-Percha Microscope Base](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/m/2904/29046456.jpeg?t=1Ttr6w)

![[CIVIL WAR] William T. Sherman CDV Portrait](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/m/3259/32590994.jpeg?t=1UVtrf)