Civil War Correspondence of William Harvey, 1st Mass. Heavy Artillery, WIA, & Brother Ira Harvey, 1st DC Cavalry

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 20, 2015 - Nov 21, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Civil War Correspondence of William Harvey, 1st Mass. Heavy Artillery, WIA, & Brother Ira Harvey, 1st DC Cavalry

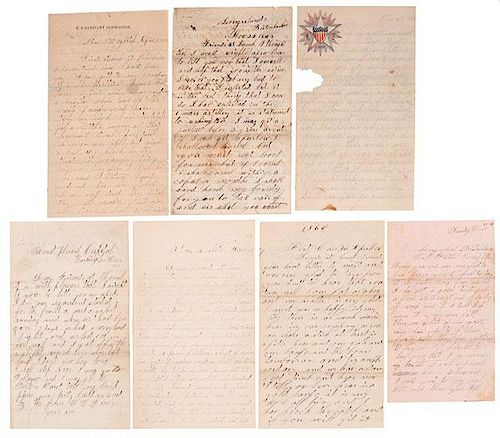

82 letters, ca 1856-1865.

Men clamored to enlist at the onset of the Civil War leaving the old, unable, or afraid behind. Brothers William and Ira Harvey enlisted just five months between each other in June and December 1863. Few of the 82 letters in this collection are between the two, but many reveal the diversity of the war experience and that for some, military life provided an escape from poverty.

William W. Harvey struggled to make a living as a painter. He enlisted when he was barely 20 on November 2, 1863 in Northampton, Massachusetts. I sopos you feal very bad to hear that I enlisted but it is the best thing that I can do, wrote William. He mustered into the 1st MA Heavy Artillery as a private. Army life was an improvement to his past circumstances, he became as fat as a hog and waid 150 lbs as a soldier. He frequently wrote to his parents telling them to use the money he sent to settle his debts, pay their bills, and purchase their house. My bounty is home, he told them. William tried to portray himself as a refined and educated. Through a litany of misspellings, he always began his letters in the tone of a gentleman and practiced his flourishes in the empty spaces.

-Not all men were as willing to enlist as William. Some wealthy families hired other men to replace their family members on the front. William had conflicted feelings about "draft dodgers." Do any of the boys listing up there now if was at homb and had ther use of both hands I would comb for a year for a bout 2 thousand for some of them rich bugs that are afraid of a draft and what do you think a bout that would they pay me purtty well... Why dont the boys list for ther contray and save the union...if they all would do as well as I have don they will put down the rebellion I am going to list a lot of them when i gitt homb....

Like many young men, William joined the military hoping to see the world and for a little adventure. Before he departed from Boston he wrote about the suffering he witnessed, there was a lot of new rebels caim hear and to of them froz to death they had nothing to lay on but blanket... It was a brief introduction to the brutality of the battlefield. On December 26, 1863, William wrote with the wide-eyed excitement of an unseasoned soldier, I am suitting up for the artillery ar agoing to start for washington at one a clock at night...my knapsack is awl packed redy to start at any minates warning.

He carried his knapsack to Washington and to Chester Hospital in Pennsylvania. On a chilly January ground, he experienced combat, which turned his innocent enthusiasm to fear. I can't wright so much now, explains William, it was a hard fight with us but thank god that I did not git killed, the bullets flew thick and fast but we had to stan ther at any rate our right got cut at very hard in the fight...William managed to evade death and injury in Pennslyvania, at Fort Cass, and in several more engagements.

Military life varied between regiments and fronts. For William's regiment music was an important diversion, there is as much music hear in our company as you can shake a stick at, said William, there is 2 fidls hear and one guth and one banjo and ther four tamboran and triangle cordan and we hav a darn good timb out hear. He pleaded to his parents to send his banjo so he could join.

His regiment leaders were staunchly conservative and punished foul mouthed soldiers while other regiments excused cursing. He wrote to his mother, you said that Grag Cason was to homb you said that he swore every word that he spoke but if he was in this regiment he would not for they would cort mashell him they hav got a boy in gard house for saying god dam it and he has bin there 4 weeks and he has bin cort marseled and they ar going to take two months pay from him so you see that it is of no benefit to swear...

William communicated with his brother, Ira. Even though there are no letters between them in this lot, he did write to his parents about their vastly different experiences, Ira was prutty lucky when he was exempt I think that the war is about over for ther Johnnies [as in Johnny Rebs] ar about plaid, they ar deserting very fast an over ___ into our army you can see the rebs from our camp purtty plain...

William was injured May 19, 1864 at Spotslyvania Court House, Virginia. Our regiment started for the front a week a go last Sunday and when we had ben gon 3 days we had a very hard fight and we lost 60 in our regt and I got off with a slight wound in my left hand I don't no how long I shall stop hear [at Mount Pleasant Hospital] I may go to Baltimore and I may go to Boston Cant tell my hand pains me pretty badd…

William was hospitalized for almost a year in several hospitals in New York, D.C., and Virginia. His injury inhibited the use of his fingers. He wrote to his sister August 8, 1864 the surgeon says that I never can do any duty in the regamint again. In another letter he wrote to his parents, I am going to apply for my discharge when I git to my regamint I will wright and lett you no how lucky I am I maybe very lucky and get my discharg soon... A wounded member of his regiment was sent to the same hospital as William he informed him that all but 10 men were captured and imprisoned by the enemy at Petersburgh. He said that they had a fight there and that I was lucky to not be there, wrote William. Frustrated by the repeated delay of his discharge, he languished in his hospital bed and continually wrote that he was no use to his regiment. While he was in Washington, he briefly mentions Lincoln's death and his funeral, but quickly returned to his discharge and lonesomeness. William was never discharged. He transferred into the 2nd Battn. of the Veteran Reserve Corps in Co. 14 on February 18, 1865. He mustered out on September 1, 1865. After the war, he worked in the Watershops department of the armory at Smith & Wesson. When reflecting on his time at war he wrote to his mother, I hav not bin over the world much yet but I no that if I never git homb that I shall no more than I did when I left but I aint sory that I enlisted...

Less is known about William's brother, Ira. Ira enlisted in Washington D.C. as a private in the DC 1st Calvary Co. D on June 1, 1863. Commanded by Col. L.C. Baker, the eight companies of the 1st Calvary were originally designed for specialized services. They were subject only to the orders of the War Department. Ira wrote most of his 9 letters while stationed in Washington around Fairfax. We doe not have any thing to doe but shoote at a target every day 5 or 6 shots a day, writes Ira. His regiment experienced little action on his front. He was more reserved with his letters and barely spoke about his regiment. His soldier's record is also in the archive. All of the questions remain blank except for his name, which he signed in his own hand. On the verso of the questionnaire is a message to his brother Ben, Sleepe in the bedroom with father.

The second part of the collection, comprised of 24 letters, come from many other family members related to the brothers dated before and after the Civil War. It gives a rare glimpse into the personal lives and the family dynamics of the soldiers before and after the war. There is one letter in response to one of William's letters. Several family members scrawl on the page informing him of their lives and their thankfulness that he received his banjo.

Orange Harvey, the patriarch of the family, had a wandering spirit. In a span of thirty years the family moved to three different cities in the Vermont area. Orange was a laborer and often traveled to find work with his older boys William and Ira. He left his wife, Martha, behind to care for their other children Mary, Martha H, and Benjamin. The children left at home (Mary, Martha, and Ben) were able to receive more of an education than Ira and William. Hundreds of miles from home, Orange penned to his wife, I will answer you I am not homesick what is the use of a diseas that a man has not got in this world...

No job or town held Orange's interest for long, he wrote from Layport May 8, 1856, I quit work laste tusday nite William is not in company with him as yeat one...I borded their as long as I wish to I think likely that I mite get work hear if I should try but I do not like well anough to start or try. Orange caught western fever and tried to homestead in Indiana, but it did not suit him. He moved on to Jericho. He writes to Martha, I like it better hear than I did in Indiana but I cannot say that it is near heaven...I presume if I had a good farm hear or in god busines that would pay well and my famaly hear I should be contented but the western fever is more excitement than reality if you should see as many that wishes themselves back as you do that wish themselves west.

A very interesting letter in the family collection does not come from Orange but his daughter, Mary. Mary writes very eloquently to her father in May 1856, We got the letter that you sent with your picture about one week ago and the miniature last night and your last letter the daguerreotype was advertised you did not put Oranges name on it and you know they are very fond of getting the copper so they laid it one side I have just been down to Mr. Ladds & Carrs and carried the picture we think it looks very natural but some what cross but I suppose you felt sober as you had to sit eight times Ben has got it now and says it looks just like pa...Will said it looks just like him...Ira has not seen the miniature yet... Martha continued school and became a servant in 1860. The next year she married Prescott Buckminster, a wealthy physician who was 28 years her senior. She had two children with him, Lillian and Ira Clyde. Prescott died in 1877, and she married James C. Hanno in 1880. Hanno was a Canadian-born farmer (and later comb maker) who was 10 years her junior. They adopted one child, Sadie B. Martha, who died in 1926 at the age of 86.Varies in condition, many of the letters from the boys are fine and legible. They all have typical folds. Several of the letters from Ira have very minor tears. The letters from the family are not in as good condition as William and Ira's. Orange's letters have issues of toning and some holes in the paper, but they do not mar the readability.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB