Civil War Cash Ledger & Two Record Journals of Henry Clay Symonds, Chief of Union Army's Commissary of Subsistence, Louisville, KY, 1861-1865

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Civil War Cash Ledger & Two Record Journals of Henry Clay Symonds, Chief of Union Army's Commissary of Subsistence, Louisville, KY, 1861-1865

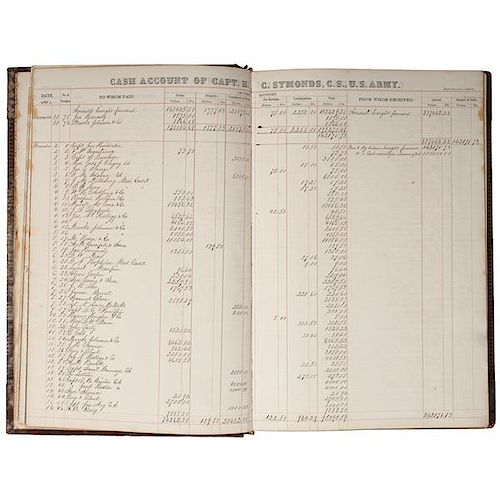

Large ledger: Approx. 11.25 x 16.25 in. suede and leather with gilt highlights, four spine bands with Capt. H. C. Symonds in gilt on spine. 124 double pages filled out. Pages are preprinted with Cash Account of Capt. H. C. Symonds, C.S., U.S. Army, and columns continue across both facing pages. The ledger was Made by Jno. P. Morton & Co. Louisville Ky. The ledger if filled with meticulous entries pertaining to orders of rations for troops stationed in Kentucky, the establishment of new depots in Kentucky, regimental movements in Kentucky as well as personnel assignments. Symonds was responsible for millions of dollars of supplies for the Department of the Cumberland, the Department of the Ohio and the Army of the Kentucky. One can follow the “action” in the patterns of these accounts. The first entry is June 3, 1861, and through June, July and August, only one “page” is taken up. September 1861 has eight lines, then October takes one and a half pages; November, two pages; then, beginning with December, all months until the end of the war typically have three to four pages each. There are gaps at the end with only October 1 – 12, 1865 recorded (on about 2/3 of a page) and only one entry for Nov. 1865 on the 27th.

Plus two 8 x 10.5 in. account books, both originally three-quarters leather over marbled paper boards. One with label on front with manuscript Telegrams. The other with label reading Endorsements on Letters.

The first has stamped page numbers and very faint blue lines on sheets. Each telegram also indicates the charge. Begins Jan 12th 1864 through August 30, 1865 (52pp). Most are of the following nature: (July 18, 1864) to Brig. Gen. Ewing: I have a herd of cattle ready to start for Nashville and cannot get an escort will you please give the necessary orders. (80 cents) And (Jany. 13, 1865, to Capt. F.N. Ehrman, C.S.) What can you buy one thousand bales of hay for and how soon? ($1.05) Followed by Buy the thousand bales and ship at once to Capt. S.D. Henderson at Nashville. ($1.15) Or (Jany. 26th 1865, to Col. F.J. Haines C.S.) We are ice bound. Can you send immediately from Cairo two hundred thousand (200,000) rations to Capt. J. McDonald, C.S.V. at Eastport. ($1.80)

There is a longer telegram to Maj. Genl. W.T. Sherman, July 17, 1864. Col. Haines and myself sent to Nashville during June, over eight million rations of salt meats. We are still sending. They are very high, and it would be most advantageous to issue Fresh Beef largely. There seems to be no want of effort in the Quartermasters, but I do not think there are cars to transport the supplies needed by your army – I do not think they can transport the Subsistence except at the expense of other Departments. The ration is not the same as before the war which will make an essential difference in the bulk to be supplied. I will urge forward as much as possible. This one cost a whopping $5.75!

The Endorsements on Letters notebook begins Dec. 9, 1864. Symonds provides a summary of the letter received and to whom it was forwarded. Sometimes he includes his recommendations. These are numbered 1 through 201 (last date Nov. 25, 1865), 69 pages. These contain more information than the telegrams, since cost was not an issue. These cover a wide range of topics. For example: No. 10. Capt S. T. Cushing forwards through me a letter to Col. R.K. Sawyer, AAG, relative to guard for Warehouses in Jeffersonville. Endorsed. Louisville, Ky. Dec. 31st, 1864. Resp’y. forwarded to Col. A.H. Sawyer AAG Hd Qrs Mil’y Div. Miss. It gives me a feeling of insecurity to have guards so often changed and apparently these changes are made merely for a notional cause. The Depot contains from ten to thirty million rations of different supplies and is of too much importance to be left at loose ends in reference to Guards. I would respectfully request, if not inconsistent with the public interest, that a Comp’y. of Inf’y. be detailed for guard to this depot and be not subject to removal except from orders from Division Hd. Qrs.

The next entry, No. 11, Letter from Major W.P. Chambliss requesting that information be given Lt. Jas. Roberts, as to how he is to obtain payment for tobacco taken at Atlanta by order of Gen. W.T. Sherman, a certificate for which was made by Capt. Blair. "Capt. Blair was in my office a few days ago and spoke to me about this subject. If tobacco was an article of issue it could easily be adjusted. Capt. Blair did it by order of Genl. Sherman. I think steps will have to be taken as if it was a claim for property taken for public use, but does not come under the act of Congress approved July 4th 1864. I know of no precedents applicable to this. It looks as if it was a case to plead for an act of grace."

No. 55. Letter No. 329 Book “A.” 1865. Capt. W.A. Elderkin refers letter of Lieut. Jas. B. Shane Comdg. Female Military Prison stating that all issues made on order of Dr. Mary J. Walker are not appropriated properly. End. Resp’y. referred to the Maj. Genl. Comd’g. Dept. of Ky.

We suspect this is Dr. Mary Edwards Walker and the middle initial was either a misreading of a clerk’s handwriting somewhere along the line, or Dr. Walker trying to “disguise” her identity using a slightly different name (but we suspect the former; Dr. Walker didn’t hide from much). Mary Edwards Walker was born in 1832 in Oswego, NY, the youngest of seven children. Working on the family farm as a child, she found “girl clothes” too restricting, and her mother insisted corsets and tight lacings were “unhealthy.” She attended local schools, becoming a teacher there to earn enough to go to Geneva Medical College. She graduated as a medical doctor in 1855, the only female in her class. Although she married a fellow medical student, Albert Miller, the marriage, and their joint medical practice, failed, partly because of public mistrust of female physicians.

When the Civil War began, Dr. Walker tried to secure a civilian contract, but initially could only practice as a nurse. She even volunteered as a spy, but was turned down for that, also. She finally secured a civilian contract with the 52nd Ohio Vols., who were desperate for a surgeon. Since part of her duties entailed care of the surrounding civilian population, she often walked about the countryside. On April 10, 1864, she encountered a Confederate patrol. She surrendered and was sent to Castle Thunder military prison in Richmond, VA. Here, also, the authorities turned down her offers to help the sick prisoners. She was paroled in an exchange on August 12, and accepted another position as Acting Assistant Surgeon. She was assigned to the Louisville Female Prison, reflected in Capt. Symonds’ letter. Even there she found little acceptance, even female prisoners of war finding her “an anomalous creature.” Like her dress in her early days on the farm, throughout the war, Dr. Walker insisted on wearing men’s pants with a knee-length jacket, a reflection of the “Bloomer” style of the women’s suffrage movement.

Although a supporter of the Union, when it came to people in need, Dr. Walker made no distinctions. She was captured after helping a Confederate surgeon with an amputation. She also showed no fear going to the front lines to help wounded men. After the war she was recommended for a Medal of Honor by William Tecumseh Sherman and George Henry Thomas. President Andrew Jackson signed the bill to present her with the medal on Nov. 11, 1865, the only woman still to hold such an honor. When the Army and Navy CMOH rolls were split in 1917, the Army reviewed their rolls, while the Navy did not. The Army revoked 911 medals, including those of Dr. May Walker (citing that she never served in combat) and William F. Cody (“Buffalo Bill”). Both of these medals, along with four others, were restored by Jimmy Carter in 1977. The Army Board stated that her acts of “distinguished gallantry, self-sacrifice, patriotism, dedication and unflinching loyalty to her country despite the apparent discrimination because of her sex” made the award appropriate.

After the war, her health, especially her vision, having been damaged in Castle Thunder, she had to give up her practice of medicine. She made her living as a social activist, lecturing and supporting issues such as health care, women’s rights (including the right to vote), dress reform for women, etc.

Nearing the end of the war, Symonds’ entry No. 87 brings up another issue – What about the millions of recently freed slaves? Maj. Genl. Palmer as per letter of Capt. Ransom relative to (?) Soldiers wives and families. End. Louisville, May 4, 1865. Wives & Children of white soldiers are not gathered into Camps. As I understand the matter, Black people quartered into camps are regarded as “contrabands” and issues should be made accordingly. If not quartered into Camps under the Special Charity of the Government, but remains at their place of abode, and are left to earn a partial support, then Circular No. 1 governs the issue.

No. 147 is one of many “downsizing” the Army: Comm. Genl. Subs. Directs Capt. A. J. Hopkins, CSV at Jeffersonville to transfer credit of Garland Hospital No. 16 Jeffersonville Ind. to the credit of Lincoln General Hospital Washington D.C. Likewise the General Hospital at New Albany, Ind. And the “Corps D’Afrique” General Hospital, also at New Albany.

Then came the question of what to do with all of the supplies, both perishable and preserved. In his note numbered 154, per the Inventory and Inspection Report of Stores (July 12, 1865), Capt. Symonds Resp’y. forwarded to Capt. E.B. Harlem, A.A.Genl. with the request that the Maj. Genl. Comdg. will order that the pickles and kraut be thrown away and that the Tongues, Hams and Salt Beef be sold at public auction. Not surprisingly, there are many more suggestions of what to do with the extra supplies. Certainly there are more interesting “tidbits” among the routine communications in this ledger.

Henry Clay Symonds was born February 10, 1832 in Salem, MA, the state from which he was accepted to USMA, which he attended from 1 Sept. 1849 to graduation 1 July 1853 (Cullum #1590), 12th in his class. He was assigned to Artillery and served the garrison at Fort Columbus, NY (1853-1854), then frontier service at Ft. Defiance, NM (1854-1856) followed by service at Ft. Independence and Ft. Snelling, before returning to USMA to serve as Assistant Professor of Geography, History, and Ethics until Jan. 1861. When war broke out, he moved to the Commissary Department (16 May 1861) stationed at the Defenses of Washington until September when he was transferred to Louisville, KY to manage the Western supply routes. It was an advantageous position, with meat packing and milling companies along both shores of the Ohio River, and access to the Mississippi, which was critical when the Ohio River froze (see his telegrams of Jan. 1865). Symonds resigned his commission in November 1865, having achieved the rank of captain, with Brevets of lt. colonel and colonel, in the omnibus awards of March 1865.

He became a merchant in New Orleans for a bit before entering the field of education. He was Principal of Vireun School at Sing Sing, NY. He also authored several books, including his Report of a Commissary of subsistence, 1861-1865 (New York: Publ. by author, printed by J.J. Little & Co., 1888). He also authored books on arithmetic, English grammar, US history and geography for the use of schools. He died in Los Gatos, CA in 1900.

The lot also includes a notebook with Symonds’ service information, a few sections of his book, and a number of pages from the ORs with items by or about Capt. Symonds. At one point there appears to have been a complaint about Symonds not providing rations to the troops. In the pages included here, he makes the case that transport was the issue, since the rebels cut the rail line between Bowling Green and Nashville. Symonds was questioned about sending supplies by river, to which he indicated that the rivers in question, especially the Cumberland and Green Rivers, were only navigable for a short time each year when the water was high enough for larger packets to navigate them. A major issue in the few chapters of Symonds’ book reproduced here had to do with the Army doing their own pork packing, rather than contracting it to local meat packers.Large ledger with a bit of mildew on long edge of front board, wear to spine ends, but in surprisingly good shape having been used daily. Both smaller notebooks also with wear, but holding together tightly. Ink is a bit light, but can be deciphered for the most part.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB