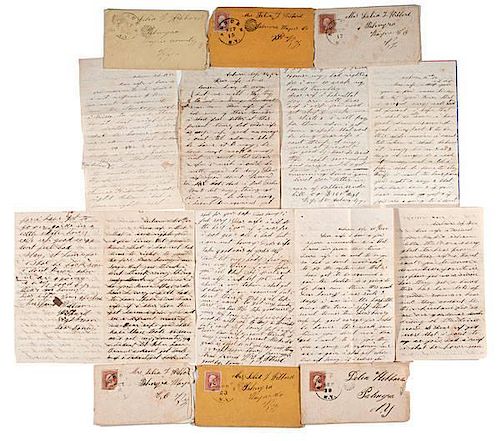

Civil War Archive of the Hibbard Family, Including William Hibbard, 160th NY, Lt. Ezra Hibbard, 111th NY, & Thomas Hibbard, 33rd NY

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 13, 2014 - Jun 14, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

52 letters (34 soldiers’ letters, 2 post-war, 16 home front), 1862-1875.

William Hibbard was a relative rarity among Civil War soldiers from New York in that he spent his entire enlistment in the deepest depths of the deep south rather than the killing fields of Virginia. A married man from Palmyra, Hibbard was mustered into the 160th New York Infantry at Auburn in late November 1862 and one month later found himself in Louisiana.

In a series of letters written to his wife Delia beginning while mustering in at Auburn, Hibbard provides a good accounting of the activities of his regiment, but more than that, an accounting of his character as a caring husband. Even before leaving Auburn, he was consoling Delia at his departure and worrying about her finances: Oct. 23, 1862: Dear honey, I am well & ingoy mu self throw the say, but when night cums I am so lonsum that I cant sleep my mind is an all the time I think of you night & day but more nights. Dear honey, I am sory that the folks are duning you so but you gust tel them to wait you must make them bleave that you are agoing to pay them when I send you the money...It would be hard to call Hibbard a literary stylist, but his letters are heartfelt and provide an excellent sense of an average soldier’s experiences. As he was preparing to head south, he wrote a last letter to Delia, filled with equal parts longing and excitement: Dear honey it is a long wayse to go & leave my dear honey be hind me it brings the tears to think of it. It is 3 thousand milds to texas but Dear wif I cant help it now. I wish I had tuck your advice & staid at home with you. Their was a grate time hear yesterday. They perzented a flage to our regmant & gave the cornel a hors worth 200 dollars but that don’t do me eny good...

In Louisiana, Hibbard’s regiment took part in their first action in January 1863 taking on the Gunboat Cotton, and they saw other small brushes along the River and at Fort Bisland. His letters are filled with the mundane details of camp life, and most are deeply affectionate, loving, and remain concerned for his wife, on her own in New York. In February 1863 he wrote to say that the work is not hard but it is so lonsum a hanging around the camp, and he complained of the boredom that was as much part of a Civil War soldier’s life as the terror of combat. There was No whair to go, he wrote, if you want to go eny whare you have got to go to the Cornel & get a pas. He is won of the meanist men that I ever met with. He is a reglar old grany. I pity him if ever we get in to battle. The hole regmant is down on him & he will find it out so byn by. All throughout, Hibbard gave advice to his wife on how to make ends meet in his absence: don’t work two hard if you are to wash for Mrs Walker I dont want you to do the washing for it is to hard to do the washing & ironing -- I know something about the work their for I have ben their.

As spring broke, the work gradually intensified as the regiment took part in the Teche Campaign and moved toward Port Hudson. On Mar. 20, Hibbard wrote about a skirmish: we was orderd out at 2 o clock we expected sumthing was up then let them cum the quicker we clean them out the quicker we will get home... our calary had a little fite with the rebel calary. Our calary tuck 5 prisners & 6 horses our men lost 4 horses they was shot...By April 30, the pressure was mounting: in 3 weaks we have ben on a march for 3 weaks we have marched 2 huntred & 20 miles had won battle it lasted won day, no body hurt in our company & killed in the regmant the big guns don the most of the fiting. I tel you the shells did fly, for sirtin, we drove them out of their entrenchmants tuck about 2000 prisners on our march...

Hibbard’s regiment took part in the general assaults at Port Hudson on May 27 and June 14, sustaining 41 casualties. His experiences may be hard to determine, but the first letter after the assaults, June 26, 1863, revealed the sad news. Charles A. Lord of 41st Mass. Infantry, a stranger, wrote to tell Delia of William’s death, though not in battle: he has ben sick with the Diarhea for some time and we done all that we could to comfort him and also the doctor he was going to send him home next week but he was to far gon. He died very easy and with a hope in Christ. One of our men went to him and ast him if he had a hope in Christ he said that he did and he was sencible to the last... the last words I heard him say was why don’t thay stop the war. The collection includes two more letters notifying Delia of William’s death.

The collection also includes six letters from William’s brother Ezra, 111th New York Infantry. While still green in September 1862, the 111th surrendered en masse during the defense of Harper’s Ferry and were paroled and sent to Camp Douglass near Chicago to await exchange. A frustrated Ezra wrote to William on Oct. 5: I hope that you will not have as bad luck as we did at harper’s Ferry. I hope that you will take good care of yourself and trust in god for he can do more for you than any one else. If you should get in a battle do not run but stand up and do your duty for I know what it is to stand to the rock for I did not run and I have wone a great many friends by doing so. If you can get a chance to pop one of those rebels I want you to do it for me for they played a good trick on us and I want to pay them for it...

Two weeks later, still Camp Douglas, Ezra seems to have found his resolve: I hope that you will think of your home and friends and if you see one of those things that they call rebels that are trying to destroy our peas and comfort that you will take good ame and fetch him to the ground. You can bet that if ever I get a cite of one of them again I will let him know that they will never take me prisoner again. I will die on the field before I will be taken.

The Hibbard brothers’ letters are not elegantly written; however they are the heartfelt, scratchy letters of a people not much used to writing, but who were effective and committed soldiers and staunch family men. An excellent record of one family’s devotion to the nation.The letters are relatively fragile, showing some wear and age toning and some separation at folds, as expected.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB