Charles Morfoot, 101st Ohio Volunteers, Civil War Archive Incl. Detailed Account of Murfreesboro and Firing on Atlanta

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Charles Morfoot, 101st Ohio Volunteers, Civil War Archive Incl. Detailed Account of Murfreesboro and Firing on Atlanta

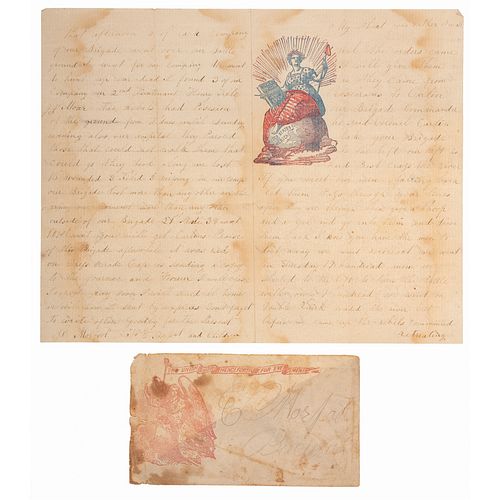

Lot of 5 letters written by First Lieutenant Charles Morfoot, 101st Ohio Infantry Volunteers, to his wife, Elizabeth, and their children, 1863-1865. His letters blend detailed accounts of battle and camp life with thoughtfully constructed literary devices, yielding unmatched, passionate descriptions of the Battle of Stone’s River, an inferno at camp, the Siege of Atlanta, and the capture of a Confederate captain’s wife to exchange for Union prisoners.

Morfoot (1823-1899), a mason from Bucyrus, Ohio, enlisted as a private on August 9, 1862. He mustered into Co. C, 101st Ohio Infantry. He was promoted twice before a transfer to Co. B of the same regiment and ultimately attained the rank of first lieutenant in November of 1864. He mustered out at Camp Harker, Tennessee on June 12, 1865.

The 101st organized at Monroeville, Ohio and headed south in September of 1862. After duty at Murfreesboro through the end of June 1863, the regiment participated in the summer’s Middle Tennessee Campaign, with engagements at Chickamauga and in the Siege of Chattanooga. Morfoot’s first two letters were written during this time, and in a letter dated January 5, 1863 from a camp near Murfreesboro, he tells his family of his involvement in the Battle of Stones River (December 31-January 2): “Well the orders came from [William] Rosecrans to [William P.] Carlin, our brigade commander. . . away we went [with] 19 hundred men. We started to the left to turn the battle with only 700. We went on double quick, waded the river but before we came up the rebels commenced retreating. We went after them with a whoop & a yell. Imagine the din of battle, there was 48 cannon belching thunder, thousands of muskets cracking, men yelling. . . I could hear wounded Rebels calling and moaning all night.” Penned on patriotic “Union Forever and Ever” stationery.

At the end of May 1863, Morfoot writes again, this time from Stone’s River, Tennessee, with news of camp life and the plight of local Tennesseeans. Making shell rings is a common camp pastime among the men, and the shells were collected from Stone’s River, “where the hard battle of Jan 2nd was fought and where we forded the river. . . some [shells] no doubt was stained with the blood of the slain.” Reminders of battle pervade the landscape, and Morfoot writes that the soundest structure he has seen is a barn with “nothing but the frame. . . left and not all that for the sheads [?] are gone, even the roof. . . such is the way the Rebs suffer here. They have nothing growing at all and not a rail to fence.” Despite the wartime atrocities, he finds Tennessee to be a picturesque locale, noting “I never saw a place I would rather live than here in Tennessee if it was free and peace.”

Next, Morfoot and his regiment travel to Bridgeport, Alabama, participating in the Atlanta Campaign from May until September of 1864. One of their most harrowing fights of the year was not “with Rebs but with fire” in February, which he describes to Elizabeth: “Fire started from the Picket Post. The wind was high, it came sweeping across the fields of dry grass like a storm towards our camp. We turned out with brushes and stopped it before it got in the woods where we are camped. Last night it got out again and came roaring in the dry leaves.” His next letter comes from a camp near Atlanta, where “the Johnnies disturb [their] peace” at night. He relates an assault from the previous evening, writing, “Two guns of our battery opened on the town. In fact, as many as 75 cannon opened all around ¾ of the city.” The Confederate onslaught continued but was ultimately put down: they “killed one man, cut one leg off another, one hand from another, killed one or 2 horses and tore a few dog tents. They kept us lying in the ditches until 2 at night. . . our guns fired every 3 minutes all night. . our shells set some buildings on fire, it appeared to be in the heart of the city. It burned 2 or 3 hours. Some say it was a large block of brick buildings.”

Morfoot and his fellow soldiers remained in Georgia, engaged in operations against Hood during the late summer and early fall before embarking on the Nashville Campaign to close out the year. January of 1865 found the 101st on duty in Huntsville, Alabama, where they stayed until March. On January 22, 1865, Morfoot writes once more to Elizabeth and tells her of his culinary exploits, executed with supplies plundered from local residences: “I have been making pies. . . we drew some flour and the boys drew peaches and apples. . . from the Rebs while out. . . they burned over one hundred houses and brought in over 20 horses besides meat, chickens, syrup, and lots of [other] things. They say it is hard to turn people out and fire their house.” Another of their spoils of war was “this guerilla’s wife, Mrs. Johnson. . . they fetched her in and left word with Johnson’s father-in-law to return our men and he can have his wife.” Kidnapping southern women was seemingly not uncommon, as Morfoot compares her behavior to that of other hostages: “the boys say they got many curses from the women, some scold, other pray and beg. [Once,] they carried a sick woman out and burned her house. . . I would like to see and hear of every building in Dixie being burned.” Includes a "Union Forever and Ever" cover with cancelled three-cent revenue stamp affixed at upper right corner.

Near the end of April, Morfoot and his regiment moved to Nashville, where they were on duty for the remainder of the Civil War, mustering out on June 12, 1865.Creasing as expected, with light toning and minor areas of staining and ink spotting.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB

![[MEDICAL HISTORY] Craig Gutta-Percha Microscope Base](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/m/2904/29046456.jpeg?t=1Ttr6w)

![[CIVIL WAR] William T. Sherman CDV Portrait](https://s1.img.bidsquare.com/item/m/3259/32590994.jpeg?t=1UVtrf)