Brigadier General James Sanks Brisbin, Civil War Archive Featuring Letter Describing the Bloody Gettysburg Campaign

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 18, 2016 - Nov 19, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

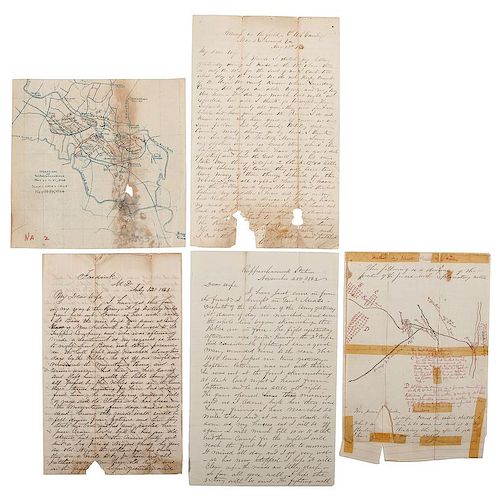

Lot of 95, comprised of 93 letters written by Brigadier General James Sanks Brisbin to his wife, Jane, from 1862-1865; 2 autographed battlefield plans for the Battle of Bull Run, approx. 7.75 x 10 in., and Operations on the North Anna River, 9.25 x 9 in.; Brisbin's presidential appointment as major, with stamped signatures of President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, dated August 20, 1866; and supplementary research documents including copies of other correspondence from Brisbin.

Anti-slavery orator James Sanks Brisbin used words as weapons. He also used a rifle. At the onset of the Civil War, Brisbin enlisted as a 2nd lieutenant on March 26, 1861 and was commissioned into the 1st Cavalry, US Army. He literally bled for the cause when the enemy shot him in his side and arm at the First Battle of Bull Run. It was the first of many wounds he earned in combat. His superiors praised him for his valor on the battlefield and promoted him to captain of the 6th US Cavalry in August 1861. Weary from battle, he wrote to his wife, I think I dated my letter yesterday evening I made it the 13th when it is only the 12th for the soul of me I cant tell what day of the week—We do not keep count of the days—We rarely know when Sunday comes—all days are alike to me and everybody else here (Camp in the Field 6th US Cavalry Near Richmond, VA, August 12, 1862).

Being a soldier was not glamorous. Sometimes, it was a very dirty job. I do not look just now like anything you ever saw except a very filthy hog, wrote Brisbin. I don’t think any one would fall in love with me in my present condition I think if we were to meet you would hesitate putting your arms around me if you did they would be apt to stick fast (Camp in the Field 6th US Cavalry Near Richmond, VA, August 12, 1862). However, sometimes being a soldier could be quite romantic. In an amazing occurrence, a woman in the 1st Cavalry, Co. B managed to disguise herself as a soldier for six months. He explained:

She is the wife of a private soldier in that Co…and no one but her husband knew who she was. She has been a good soldier and been in two battles. She did her duty faithfully and no one or a moment supposed her to be a woman. She looks like a boy of sixteen has black hair and eyes and is quiet and modest and [illegible] wonder why she was not discovered sooner but officers do not suspect such things and in the regular service we have so little to say to our men a woman might be in a Co. a year and the officers not know it. She enlisted to be with her husband and escaped the examining surgeon—She will be sent off immediately as it is against Army regulations for a woman to be a soldier (Camp in the Field 6th US Cavalry Near Richmond, VA, August 12, 1862).

The spring of 1862 resulted in several demoralizing Union losses. Brisbin loved his country, but blamed Washington for the recent failures rather than his leader, General George McClellan. McClellan’s men loved him more than Lincoln did. McClellan frequently delayed his attacks which allowed the Confederate Army to rebuild. The sluggish strategy led to a series of embarrassing defeats, which risked his position. Lincoln removed McClellan as General-in-Chief and replaced him with Henry Halleck. Lincoln eventually gave the Army of the Potomac to General John Pope. Disgruntled about the treatment of his beloved general, Brisbin wrote to his wife:

When McDowell got thrashed at Bull Run they sent for Mac to come and save Washington he came and fixed up their army for them and then they threatened him like a dog and got Pope well Pope got hell and sent for Washington and his army at his heels the Govt. got scared and telegraphed to McClellan to come quick and save Washington he came drove back the rebels followed them back to Antietam and with the very men that they had licked under Pope McClellan licked them and was driving them back to Richmond but as soon as the Govt. and Washington felt it was safe it began on “Little Mac” again and finally turned him off again don’t be surprised when if it should happen the Govt. will begin to shake and call on Little Mac to come and save them and Little Mach will come for he is a good man and loves his country dearly (Bull Plain, VA, December 1, 1862).

Failing to learn from his past mistakes, McClellan still waited too long to attack his enemies. At Bull Plain, VA, Brisbin participated in an agonizing delay. Every day we lay here the rebels are improving by making their works stronger—what we are waiting on no one knows—I doubt we are going to cross here at all, wrote Brisbin (Bull Plain, VA, December 1, 1862). Yet, he still did not blame McClellan for the poor choice.

As McClellan’s career began to decline, Brisbin’s steadily rose. On June 9, 1863 he was brevetted a major for his conduct at Beverly Ford, VA. Rising through the ranks allowed him to keep impressive company, but did not keep him from risking his life on the field. From Rappahannock Station he wrote:

I brought General Meade dispatch of the operations of the army yesterday. At dawn of day we marched and soon the whole line began skirmishing the Rebels are in force. The fight yesterday afternoon was quite heavy…I saw a good many wounded come to the rear…The guns opened up this morning and as I came back here there was heavy firing…I hope the victory will be ours. The fighting will last 4 or 5 days. The Rebels are strong but we are stronger…I hope I will be spared (Rappahannock Station, November 28, 1863).

He was spared, but many officers and soldiers did not share the same fortune. Two of Brisbin’s friends, Lieutenant Boaz and Captain Cram, were briefly captured by the enemy during the Battle of Fairfield which was part of the Gettysburg Campaign. When they returned to camp, Brisbin wrote his wife about their experience:

[Lt. Boaz] got off one night and ran into the mountains Penna(?) and a union woman hid him in her garret and help him until the Rebel Army had all passed by. The rebels were in the home three times hunting for him but did not find him. He was laying under a pile of rags and old clothes. He has been in the mountain four days and is nearly dead. Cram they made him walk until he fell down from fatigue and then they took his boots and hat and paroled him poor Cram looks bad as he has an old straw hat with the crown half out and a big pair of n****** shoes he gave an old n***** ten dollars for his shoes they are a mile to big for him and all patched over (Frederick, MD, July 12, 1863).

Many men and officers also died. There are now only eight men and two officers in the whole Regt—is not that truly awful, wrote Brisbin. Only three are left in my company…so I have no Regt to command…The regiment has covered itself with glory but few are left to tell of its great deeds. Oh it makes me sick to think of the slaughter of the old sixth—how I love it—may God save the few that are left (Frederick, MD, July 12, 1863).

With no men left to command, he planned to speak with Meade and request he send him with Hooker. The army thought otherwise. He remained with the 6th until he accepted a commission as a colonel of the 5th US Colored Cavalry on March 1, 1864. He participated in the Red River Campaign in Louisiana under the direction of General Alberts and received two promotions in the month of December; brigadier general by brevet and lieutenant colonel by brevet. Throughout 1865, he received a series of promotions, reaching the rank of brigadier general on May 1, 1865. The archive offered ends with his Civil War service.

According to the Montana Historical Society, Brisbin remained in the regular army after the war, aiding in the establishment of the Freedman's Bureau and in organizing the colored regiments. In 1868 he was stationed in the west. In an earlier letter offered in the lot, he encouraged his wife to practice her riding every day so she could go along when [he went] out on an Indian chase (Camp in the Field 6th US Cavalry Near Richmond, VA, August 12, 1862). He participated in many Indian chases there. Brisbin had such a fear of losing his wife, she most certainly did not join him on his pursuits. However, she most certainly enjoyed riding with him through the plains. She died at Fort McKinney in 1887. Brisbin offered his services to General Custer before his defeat at Little Big Horn. Custer refused, and declining Brisbin's offer most likely saved Brisbin's life or career. From 1868 until the time of his death in 1892, he served in the northwestern United States as an officer in several cavalry regiments, including the 2nd, 9th, 1st, and 8th regiments. During his western career, he was a staff officer, battalion or squadron commander, post commander, and regimental commander. He served at Fort D.A. Russell, Fort Pease on the Yellowstone River, Boise Barracks, Omaha Barracks, Camp Stambaugh, Fort Ellis, Fort Assiniboine, Fort Keogh, Fort Custer, Fort Niobrara, Fort Robinson, Fort McKinney, and finally at Fort Meade in South Dakota. (Information obtained from Archives West: James Sanks Brisbin Papers, October 1, 2016.)

Most of the letters are in very good condition with typical folds and toning of the paper. Some are in poor condition and are fragile with some tears and small missing portions of the letters.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB