Brig. General Thomas Tinsley Heath, 5th Ohio Cavalry, Civil War Footlocker & Manuscript Archive

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 12, 2015 - Jun 13, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

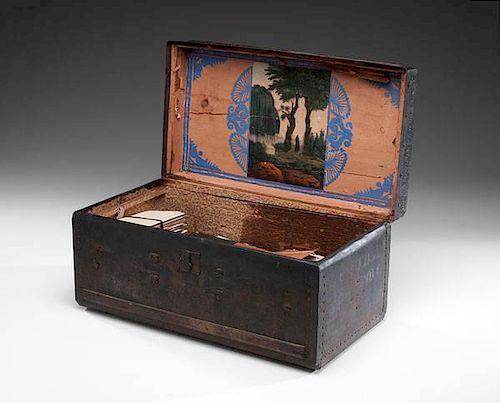

Lot of over 900 orders, letters, and other paper items in a footlocker, 24 x 13 x 11.5 in. with (Gen.?) T.T. Heath / 5th OVC lettered on one end, leather covered with metal strips on the corners held with tacks, and strips of wood (“bumpers”) on top and long sides of wood. Inside top is a lovely print of the kind often seen in memorial art. The bottom lined with wallpaper.

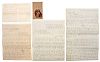

The lot includes a large lithograph of Heath, 7 x 9.5 in. plate on an 11 x 14 in. heavy paper stock, with facsimile signature. Printed by “Western Biogl. Publ Co., Cin. O.” A cdv that is included in the trunk is of Samuel Riggs, whose house was burned by Quantrill’s Raiders in Lawrence, KS. It is not clear why this cdv is here, but the 5th OVC spent most of the war in the Western Theater, and could have encountered Riggs or one of his friends. (According to legends of the day, Riggs’ wife saved his life by holding the bridle of the raider’s horse, giving her husband just enough time to duck for cover before the shooting started, then escape through the back of the house to the nearby woods. In many ways, Lawrence was inspiration in the West in the way Ellsworth was in the East.)

The collection is composed of several packets of papers. There are nearly 300 war-dated items that include orders, telegrams, ordnance inventories. In addition, since the 5th OVC served for several months after the war ended, there are nearly 200 items dating between mid-April and the end of 1865. These consist of over 100 orders, etc. There is a bundle of over 70 military telegraph messages from this period, and even 14 commissions dated 4 Sept. 1865, all for men who were never mustered into those positions.

In addition the archive contains close to 300 letters: at least 6 from 1862, 83 from 1863, 108 from 1864 and 15 from 1865-1866 (some envelopes contain multiple letters). Most of these are to Heath’s wife, with a few others to and from his mother, sister, and brother. There are, in addition, over 80 letters that are mostly military in nature, many men wanting commissions, paroles, men on sick leave, reports needed. A couple soldiers wanted to get out of prison, one stating he would gladly serve in the unit, and that dying in battle would be better than rotting in prison. Another poignant letter came from a young girl stating that both of their parents had died and that there were several young children still at home. She asked if Heath could send her brother home to take care of them.

The material tells the story of one Ohio cavalry unit, initially numbered the second cavalry, but subsequently changed to the 5th. After recruiting and organizing at Camp Dick Corwin, the unit moved to Camp Dennison for training. After several months in camp, the unit was getting bored. There is a retained copy of a letter from Heath to John Gurley at the War Department requesting an assignment. He gets a bit “testy”: “Is it the policy for the Government to keep 1200 good cavalry troops cooped up in Camp Dennison all these months? Do our countrymen care for us now that we are enlisted and deprived of home comforts and society? Are we forgotten, and consigned to hopeless oblivion, without a possibility of forcing ourselves into notice by honorable actions in the country’s service? …. Cannot you find for us some General who can use Cavalry – is there not some place where we can aid our country in her hour of need? …We want pistols and carbines at once, and we are ready for any work, in any quarter that the United States of America can best use men. We will go East, West, South or North, anywhere and cheerfully, if orders can be procured.” Endorsed by Gen. George Ruggles. Another letter is on Adjutant General’s Office, Washington letterhead, with a March 27, 1862 date. “I have the honor to return to you, herewith, the letter addressed to you by Lt. Col. Heath, 5th Ohio Vols. The subject of this letter will be immediately brought to the attention of the War Department.” This is shortly after he wrote for an assignment, and could have been making its “rounds” in Washington.

The unit was shipped out in short order to Paducah, KY, and thence to Pittsburg Landing, TN. In the earliest letter in the group (unfortunately missing a section), he writes to his then-fiancé: Pittsburgh [sic] Tennessee, March 20th 1862 / My Dear Mary – I was so suddenly called away from Camp Dennison, and that too with the advance of our regiment and was charged with the case of everything so heavily that I found it impossible to run up and take a farewell kiss and tell you once again “Good Bye” – and too, I confess I was fearful to see your tears and hear you sob at my departure. I left Cincinnati on the 28th of February, reached Paducah Ky on the 2d of March, and was immediately ordered to Fort Henry on the Tennessee River….” They were engaged in minor skirmishes and scouts before arriving just in time for the battle at Shiloh/Pittsburg Landing. Reportedly Col. Taylor was ill, leaving command of the unit to Lt. Col. Heath, who impressed many, including Generals Grant and Sherman, in mounting the only cavalry charge of the engagement.

Things seem to have gone relatively smoothly for the first year, although Col. Taylor appears to have been absent with various illnesses during much of the time. Then Heath got into some kind of trouble. There are numerous papers included in this lot that relate to courts martial, including his own. Apparently Col. Taylor filed charges against Heath for “Conduct Unbecoming….” In a pair of letters dated March 6 and 9, 1863, Heath writes to his wife: [6] “I did not tell you Mary who was being court martialed, because I could not tell you all about it – but now that it is over I can tell you. It was your husband who was being tried on charges of “Disobedience of Orders” preferred by Col. W.H.H. Taylor. I was for 3 weeks on trial, and after Co. Taylor swore all he could, and got all his friends to swear all they could, the court notified me that I need not produce a single witness and they unanimously acquitted me of every charge and every specification. This course of Taylor’s was the crowning act of his infamy, and now for me the sympathy of every man here – It decided me as the commanding officer of the regiment, and showed to all that he was falsely charging me out of petty jealousy and spite.” [9] – “I have just heard something which makes me fear you have spoken to somebody of the contents of my letters to you. For Gods sake don’t speak to anyone of a word I write you. You might plunge me into trouble by a little indiscretion which would ruin me. My letters to you are not to be seen by anyone. Ever your husband, Heath.” (He usually signed his letters “your affectionate husband” – not this time!) In a separate letter Mar. 12, 1863, he again notes: “There is much bitterness of feeling on the part of Col. Taylor toward me, but I have the inside track and I intend to keep it. I am in command, and I always expect to be until after Taylor is out of the service. I heard the other day a remark dropped which made me fear that spy’s even on your track. And even telling the conversations you had about your husband and the manner in which Col. Taylor treated him.—There can be no mistake about it. Somebody had told some expressions dropped by you or some of your family…. I earnestly ask you never at anytime to permit yourself to speak of anything I write you…”

It is unclear whether Taylor again filed charges, although it appears so, since Heath was ordered arrested again in mid-April. He later notes that Gen. Hurlbut was willing to file any charges Taylor brought, but refused to file charges brought against Taylor by Heath. One item in this lot is an undated sworn statement taken in Memphis from William McFarland, formerly 1st Lieut. And QM of the 5th OVC who stated that when he applied to Taylor for the QM position, Taylor told him he could have it for $600. Hurlbut apparently gave Taylor a F&S position and the two men often shared officers’ quarters.

There is a packet of receipts, etc. that appear to relate to family matters during the war. One item in the packet is a letter signed by Taylor and approved by Hurlbut allowing both Thomas and William Heath leave to return to Ohio to bury their father. Could this be related to the court martial charges? Another possibility relates to a letter from Nelson Reuben Derby, Surgeon, stating that Heath was extremely ill in May 1862, and Derby recommended that he retire to a more northern climate to recover. He was carried to Pittsburg Landing and put on a boat for home (we believe somewhere in here is a note that William accompanied him, since he was not capable of going alone). Possibly Derby had them leave, but Taylor did not approve, or thought the surgeon was going over his head? A letter from Charles S. Hamilton dated 2 Feb. 1863, restores Heath to service, since he had been inadvertently mustered out during an illness (not necessarily this illness).

Ultimately, Taylor left the service and Heath was promoted to command of the 5th OVC, and, although he had no formal military training, he threw himself into the task. One of the first things he seems to have done was bring others up on charges – “housecleaning.” He got rid of others accused of corruption or inefficiency, and got appointments for his own choices. He had been a lawyer before the war, so there are many papers of a legal nature, both in his own court martial cases and others – some of them men he was forcing out of the 5th OVC. [We have a feeling there was also more to this than meets the eye. There were letters in different packets in here that we think are associated. There was a letter from a former member of the unit thanking Heath for getting him discharged to handle family matters. But there are other letters indicating that the army was not granting discharges for any reason, and we think this soldier was one of the court martial cases – the next owner might look into these. Did Heath trump up charges to get one of his men out of service when other options failed?)

By the end of the war, Heath had one of the best-disciplined units in service. He tells his wife: [Nov. 12, 1864, Marietta, GA.] “The Officers of this new Cavalry Corps were last night invited to attend a meeting of Ceremony at General Kilpatricks Hd Qrs. I took my officers up and introduced each one of them, and I never felt prouder, for I had 16 of the finest looking, best drilled and best dressed officers in the assembly… I may not get another letter from you for four weeks or more, as after we leave this place we will not again see our own people until we get to the sea coast and meet the Fleet,…” This marked the beginning of the Savannah Campaign, Nov. 15 – Dec. 21, 1864, otherwise known as Sherman’s “March to the Sea.”

Sometimes one can follow movements in these telegrams and orders:

Nov. 16 [1863] Telegraph from WT Sherman: Leave property in Corinth and move forward. “If there be any shelter tents I will approve your Requisition but the less you encumber yourself, the better.”

Nov. 26, 1863 – Special Field Orders to escort a train of supplies & ammo to 15th AC, by order of Osterhaus, approved by Maj. Gen. Grant.

Dec. 8, 1863 - Telegraph from Sherman – push forward with the best of your men & horses to Tellico Plains – remain until we come up.

Dec 15, 1863 - reinforce Col. Long, guard RR bridge at Charleston – “[you] will subsist on the resources of the country till other arrangements can be made.” By order of WT Sherman.

There are other items such as one letter – sent postage due – from Thomas Hare which basically states that he is a prisoner of war. He also lets Heath know others are there, also. “Major Henry is here. He is well.” There are receipts for prisoners taken by Heath’s unit, including one “rebel deserter.” (As supplies and materiel became critically short in the Confederacy, many soldiers deserted to the North for a meal.)

About the same time as Sherman began the second leg of his “cross-Confederacy trek,” the 3-year enlistment for the 5th OVC was expired. The wheels of the Army move slowly. There were a few communications in October relating to the impending muster out, and by 6 Nov. 1864 a list of 6 captains was sent, all were to proceed to Ohio to be mustered out. Then little seems to have happened, but Sherman’s campaign may have hindered the mustering out to an extent. By the end of December, Heath again gets a bit testy. A letter (and drafts) dated 22 Dec. 1864 state that he has served beyond his enlistment term and his family needs him; if it is essential to remain, he would like a 30-day leave, during which he would be willing to recruit other officers and men while at home. Although this sounds a bit selfish, other units who veteranized during this period were granted 30-day leaves before returning to their units. As always, some men would leave service and some would veteranize during these reorganizations. There is a significant bunch of material related to a major recruiting push in Jan. and Feb. of 1865 in which William McKendree Heath was in Cincinnati to recruit, presumably to help fill the ranks to full strength after losing those who chose to leave.

Also during this later period, the unit decided on a regimental flag and requested Mrs. Heath (“Lady Heath”) to make it for them. The lot contains a short description of the flag (“Of yellow silk, Twenty Two (22) inches fly – Eighteen (18) inches on the pike. The pike including spear and ferrule to be seen (7) feet in length – The fringe of the colors to be silk. In the centre two cannons crossing – with the letters U.S. above – “5th Ohio Cavalry Howitzers” below – Cords and Tassels red and yellow silk inter.”) plus a small pencil sketch of the flag and the letter requesting her to make it.

A group of three letters concerns making arrangements in Jan. and Feb. 1865 to bring Genl. Hooker’s horse, “Lookout,” to Cincinnati [signed by Joseph Hooker], and a letter to Heath from Edward Wolcott “If there is room in your stable please let the horse remain there and allow one of your men to take charge of him.”

Not only did the 5th OVC become a veteran unit, it was retained after the surrenders. This material contains an even larger variety of material, if possible. There are complaints from citizens about horses and mules being taken, the need for more police, the resignation of the Albemarle police commandant, a note from citizens to get military prisoners out of their jail, a horse found wandering that has a US brand, statements about a murder in Yadkin County, and witness statements identifying the murderer, plus orders for Heath to round up a suspect in the murder of William Smith (accompanying a petition signed by 28 men of Carwell County, plus a description of the suspect), requests from other units to be mustered out, especially a couple of Pennsylvania units, orders to retain the band until Heath returned [June 21, 1865] (he apparently returned home shortly after the war ended for a leave). There were orders to stop allowing armed men to gather or meet during the campaigns, and to emphasize that order must be kept during elections. One letter dated 14 June 1865 notes that John Garret and Joshua Bullock were arrested for whipping a negro woman, that also indicates that it was difficult to restrain citizens from whipping freed men.

While in North Carolina, Heath picked up several Confederate letters. One was a docketed wrapper dated 6 Feb. 1865, Raleigh, signed by aides of Lt. Gen. Holmes, at least one adjutant, and a note “Disppd. Th.H. Holmes.” (Theophilus Hunter Holmes (1804-1880) was a Confederate Lt. Gen.)

There is a letter to Maj. Gen. Schofield, June 3, 1865, letter from John Johns Jr., late 1st Lieut CSA, informing him that he had in his possession a pair of mules & wagon in lieu of $1400 owed him by the Confederate govt. (so no one thinks he stole them) – Docketed by J.A. Campbell, Schofield’s AAG, also sgd. by J. Kilpatrick, and Thomas Heath.

One very dirty manuscript Special Order No. 5, Aug. 28, 1861, has a pencil note on verso “Picked up at the battle of Stony Creek Va.” Signed by Col. Milo Smith Hascall’s AG.

There are autographed letters and notes by: Gen. Albert Lindley Lee (plus a shorter note); Maj. Gen. Stephen Augustus Hurlbut (1815-1882); 5 letters by Edward Wolcott in addition to the one above; Grenville Mellen Dodge (1831-1916); Brig. Gen. (Bvt. Maj. Gen.) John Eugene Smith (1816-1897), 2 ANsS; Edward Moody McCook (1833-1909), one of the “Fighting McCooks;” P. Joseph Osterhaus [Peter Joseph Osterhaus (1823-1917)]; Charles Smith Hamilton (1822-1891); James Clifford Veatch, Brig. Gen. (1819-1895); Adelbert Ames, Bvt. Maj. Genl. (1835-1933) – CMOH Manassas; and Green Berry Raum (1829-1909).

In addition, there are documents docketed or endorsed by: J. Kilpatrick [Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (1836-1881)]; Brig. Gen. C. R. Woods (Charles Robert Woods (1827-1885); Coates Kinney, paymaster and later Poet Laureate of Ohio; Maj. Gen. John A. Logan [John Alexander Logan (1826-1866)]; John E. Smith (as above); Maj. Gen. James B. Steedman [James Blair Steedman (1817-1883)]; W.W. Holden, Governor of North Carolina; J.A. Campbell [John Allen Campbell, Bvt. Brig. Gen. (1835-1880), Schofield’s AG]; Geo. B. Dyer, Maj. Gen. Vols. & Prov. Marshal [George Burton Dyer]; Hugh Ewing, Brig. Gen. (1826-1905); George Shumard (Medical Director, District of KY); and Brig. Genl. B.H. Grierson [Benjamin Henry Grierson (1826-1922)], plus others not listed here.

There is a map, approx. 19.5 x 29 in. on very thin tissue paper, “Map of the Northern Portion of the State of Mississippi.” Bottom edge is torn, either from a book or part of it is missing.

The archive includes four books, at least a couple of which must have been used by Heath to train his regiment:

Craighill, William P. The Army Officer’s Pocket Companion; Principally Designed for Staff Officers in the Field. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862. 16mo, full leather, marbled end papers and page edges, 314pp.

Cooke, Philip St. Geo. Cavalry Tactics: or, Regulations for the Instruction, Formations and Movements of the Cavalry of the Army and Volunteers of the United States… Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862, Vol. II. 16mo, embossed cloth, gilt spine lettering, 108pp plus 12 pp ads.

Stephens, Thomas. A New System of Broad and Small Sword Exercise… to Which are Added Instructions in Horsemanship, … Milwaukee: Jermain & Brightman, 1861. 12mo, embossed cloth, gilt front lettering, 116pp. Inscribed and signed by author.

The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America. New York: R. Spalding, 1867. 8vo, embossed device front and back, highlighted in gilt on front, 86pp. Clipped signature of George Washington affixed to p. 74 (below a facsimile signature)

General Thomas Tinsley Heath (1835-1925) was born in Xenia, OH to Rev. Uriah and Mary Ann Perkins Heath, his father being one of the leading Methodist preachers in the Ohio Conference. Not surprisingly, his father also was an abolitionist and advocate for higher education, being a trustee of both Ohio University and Ohio Wesleyan University. The children read the Bible before entering school. Both parents also had ancestors who served in the Revolution, instilling a spirit of military service in their children. Young Thomas did not, however, follow his father into the ministry, instead being determined to practice law. He later specialized in business, patent and estate law rather than criminal or general practice.

When the news of Fort Sumter reached Heath, he closed his law office in Cincinnati, and petitioned Washington to allow him to recruit three regiments there. Under authority of General Fremont, he recruited, organized and equipped the Fifth Regiment of Ohio Cavalry. Since he had no direct military experience, he refused the colonelcy of the unit, but recommended William Henry Harrison Taylor, a nephew and son-in-law of President Harrison for the post and accepted the Lieutenant Colonelcy for himself. The unit organized at Camp Dick Corwine near Cincinnati; in November 1861 it moved to Camp Dennison (eastern Hamilton County, OH) for training.

After a period of time, Heath tired of recruiting, training and drilling troops and was itching to get into the field. In the spring of 1862, just before the campaign season began, he wrote directly to Secretary of War Stanton telling him that he had 1200 trained and equipped cavalry sitting at Camp Dennison, all of whom enlisted to help the Union. If Stanton didn’t want their help, they would go home. Otherwise, they would like to be sent where they could help. A retained copy of this letter is in the first archive. Stanton reportedly read the appeal to a room full of people, approved the appeal and within two days, Heath and his cavalry were on steamboats headed down the Ohio River (although technically only 1142 strong). About the 16th of March they landed at Pittsburg Landing, and set out on a night march to destroy a railroad at Iuka. About 300 yards from Shiloh Church, they were attacked by Clanton’s brigade of Alabama Cavalry. They had arrived in time to aid Grant in the battle that took its name from that same church three weeks later, on April 6-7. Col. Taylor became ill, so Lt. Col. Heath led the only cavalry charge made in the battle at Shiloh /Pittsburg Landing. The regiment was under constant fire, directly under Grant’s command. And, even though it was a raw regiment, both Grant and Sherman gave it high marks. The 5th OVC remained with the army through the siege of Corinth. Colonel Taylor’s health forced him to be absent much of the time, effectively leaving Heath in command. When Taylor was detailed to court-martial duty in late 1863, Heath decided to reorganize the regiment, weed out incompetent officers and institute discipline and education.

It remained primarily in the Western Theater until it veteranized in spring of 1864. It then joined Sherman on his March to the Sea and through the Carolinas. It was retained through the fall of 1865, mustering out at the end of October. During the military reconstruction Heath appointed justices of the peace, paroled rebel soldiers, and made sure the civilian government was functioning in 57 counties of the Carolinas. Many of the documents in these lots relate to these efforts.

Before the war, Heath was engaged, but postponed the wedding because of hostilities. He did procure a week’s leave in Nov. 1862 to come home and be married to Mary Elizabeth Bagley. He got home once a year during the war, and she was able to visit him on two occasions, then joining him in North Carolina after the surrender. The couple never had children, and she died in 1872. Four years later he was married to Mary Louise Slack of Middletown, Ohio. This union produced four sons and three daughters, although two sons died of diphtheria in 1889. Heath built a home in Loveland, “Miamanon.” He was also active in the Methodist Episcopal Church in Loveland, and many receipts for purchases of building materials are in lots 104 and 105, along with communications with pastors of the church. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB