Black Hawk War-Period Letter, May 1832, Discussing Attacks Near Dixon's Ferry

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 10, 2016 - Jun 11, 2016

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Black Hawk War-Period Letter, May 1832, Discussing Attacks Near Dixon's Ferry

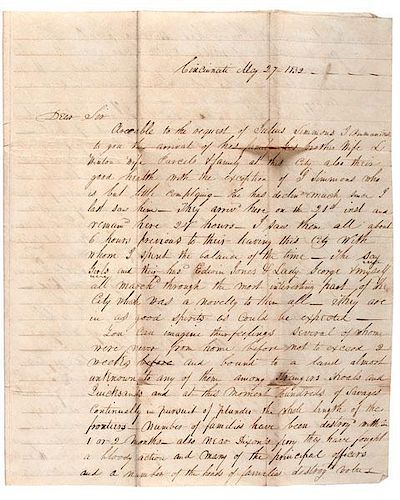

ALS, from "Stanley Sherwood," 4pp, Cincinnati, May 27, 1832. Traveling during the bloody conflict between the Black Hawks and Americans made an already dangerous journey Westward even more harrowing. In this descriptive letter, the author writes to Captain G.C. Huinan in Tioga County, NY, to inform Julius Simmons of his family's safe arrival en route to Illinois.

You can imagine their feelings several of whom were never from home before not to exceed 2 weeks and bound to a land almost unknown to any of them, among strangers, shoals and quicksand and at this moment, hundreds of savages continually in the pursuit of plunders the lengths of the frontiers, wrote Thurman. Members of families have been destroyed within 1 to 2 months--also near Dixon's Ferry they have fought a bloody action and many of the principal officers and members and heads of families destroyed.

He continues to write about the land and soil in other parts of the developing country, including Cincinnati. He wrote, With the exception of New Orleans, Cincinnati is the largest in the South West and as to beauty, not one exceeds it. Within the course of 35 years it has risen from a village of soldiers huts to a splendid city and still giving promise of the future splendor to any on the sea board perhaps...

Although the proximate cause of the Black Hawk War is a bit ambiguous, it has its roots in a couple of events three decades earlier. As Governor of the Northwest Territory, in 1804 William Henry Harrison negotiated a treaty with the Sauks and Meskwaki/Fox tribes of what would become Illinois to cede land east of the Mississippi River and move to "Indian Territory." According to tribal leaders, who knew they would have to cede some land to the Americans in the treaty negotiations, what they were told they were giving up and what was written in the treaty were very different - an accusation commonly made by native peoples in the 19th century. The other tribal members also contended that the chiefs had no authority to give up those lands.

To complicate matters, the native peoples were permitted to continue using the land until it was sold to white Americans. The US finally got around to surveying the lands for more than a decade and began awarding the lots to veterans of the War of 1812 and others who had not received bounty lands in other parts of the Northwest Territory from earlier service. About 1828 Indian Agent Thomas Forsyth informed the Sauks that they should vacate their town of Saukenuk and all territory east of the Mississippi.

It appears that a group of Sauks along with closely allied Meskwakis decided that this was not what they had signed up for, and recrossed the Mississippi to settle on their former lands. Black Hawk, a Sauk war chief, emerged as the leader of the band that decided to resist the implementation of the treaty of 1804. They do not seem to have wanted any violence, just their former communities. After their winter hunt in 1829, they returned to Saukenuk to find it occupied by white squatters. There was the inevitable conflict, and in September, the natives again left for their winter hunt. Again, when they returned, they found it occupied by whites.

By this time Black Hawk had picked up others, such as a group of Kickapoos and some Potawatomis. The group became known as the "British Band," sometimes flying a British flag to signal opposition to Americans.

By the time the British Band returned to Saukenuk in 1831, they found American soldiers under General Edmund Gaines waiting for them. Gaines had no cavalry, so he requested a mounted state militia battalion. However, by the time he was able to assemble all of the pieces, Black Hawk had slipped back across the Mississippi. The native leaders met with Gaines and promised to stay on the Western side of the river.

That did not last long. Late in 1831, Neapope (Sauk) reported that the British and other Illinois tribes would support the "British Band," a report that turned out to be untrue. Then later, Wabokieshiek, the "Winnebago Prophet," also claimed that other tribes would support Black Hawk. Some blame Wabokieshiek as the primary instigator, others claim he told his followers not to engage in armed violence. Whatever the case, Black Hawk again crossed the Mississippi in April 1832. He had a party of colonists - women, children, the elderly - not a war party.

What happened after this was also tied to intertribal warfare, with several individuals in the British Band accused of killing some Menominees in July 1831. The Army decided to pursue the perpetrators, and Brigadier General Henry Atkinson, filling in for the ill General Gaines, was convinced the Indians wanted war. Although there are indications that Black Hawk realized that without British and Potawatomi support he could not win and intended to negotiate a peaceful solution, a contingent of Illinois mounted volunteers who were supposed to just reconnoiter the strength and location of the British Band went a step further, arresting a party approaching under a white flag of truce and opening fire on the observers in the distance. Black Hawk's warriors predictably retaliated, and the war was on. Before it was over in late summer, nearly all of Black Hawk's band, including the non-combatants, were killed.

Among those who saw military service in this brief conflict were Abraham Lincoln, Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, and Jefferson Davis. This marked the end of the Indian Wars and resistance to American expansion in the Northwest Territory. It also fueled Andrew Jackson's policy of Indian Removal.Very good, typical folds on the letter, some toning of the paper.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB