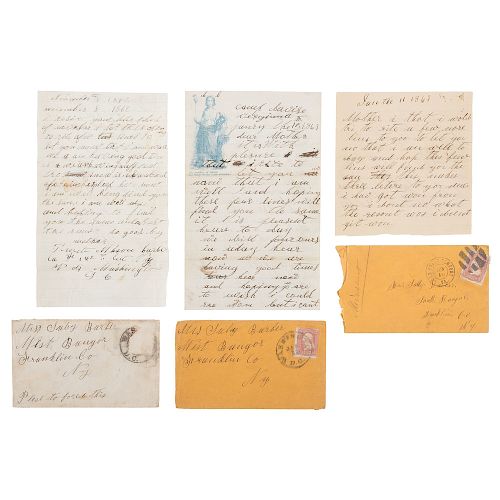

Battle Content Letter Archive of Private Watson Barber, 142nd New York Volunteers, 1862-1865

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 21, 2019

On June 21, Cowan’s Auctions will be offering a remarkable selection of historic photography, letters, documents, flags, political ephemera, and more representing the Revolutionary War-period through the Civil War, Indian Wars, and beyond, as well as the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Lot of approximately 48 documents, including 37 riveting letters written and received by Private Watson Rufus Barber (ca 1845-1912) of Bangor, NY, during the years 1862 through 1865. His mother, Sally Ewing Barber (1817-1892), was his primary correspondent, though he also wrote to his brothers Henry LaForest Barber (1843-1928) and Orville Fillmore Barber (1850-1931). Collection additionally contains Barber's discharge papers, manuscript records of his participation in marches and battles, and pension documents addressed to his wife, Almera (1851-1916).

Barber enlisted as a private in Bangor on August 29, 1862. He mustered into Co. F, 142nd New York Infantry. He begins writing home almost immediately, requesting news from home and reporting on his health. Later, his carefully recorded accounts chronicle the movements of his regiment and battle details, including engagements at Bermuda Hundred, Petersburg, and Fort Fisher.

To begin, Barber writes from different locations in Virginia, including Camp Bliss, one of several large Union army encampments surrounding Fort Upton in Arlington County. In one of his earlier letters, dated January 25, 1863, Barber tells his mother that he has acquired a “new pair of pants ” and encloses a small piece of fabric from his uniform (included). The closing of this letter reveals Barber’s great spirituality, a theme he revisits frequently in his correspondence, particularly during difficult times: “I want you to look to C[h]rist. We shall have a seat on the right side of C[h]rist in heaven. Give me your prayers[?] that I will go to heaven. ” In the spring of 1865, after nearly three years away, Barber tells his mother that “if we don’t meet again on Earth, we must be prepared to meet in heaven where parting will be no more .”

From Virginia, Barber and his regiment move to South Carolina during the summer of 1863. His letters from Folly Island and Kiawah primarily concern his pay, which he dutifully sent home to keep the family farm running. In the spring of 1864, he found himself back in Virginia, stationed first at West Point and then “on the South Side of the James River about ten miles from Richmond .” From this location, he describes events from the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign in a letter dated June 23, 1864: “We had a fight on the 15 of this Month at Petersburg, we drove the rebels and took 4 hundred prisoners and 13 cannons. ” Watson spent the rest of the summer in the hospital, before rejoining his regiment in time to march to North Carolina. On January 18, 1865, he provides an account of the Battle of Fort Fisher: “We took the fort called Fort Fisher and 25 hundred prisoners in the fort. This was a hard fight. This was done on the 15th of this month. We took 60 big heavy guns. We had to fight like dogs to get the fort but now the fort is ours .”

Barber rarely discusses politics or expresses his feelings regarding the Union cause, but he does profess support for President Lincoln following his reelection in November of 1864: “Abraham Lincoln is our President, he is just the man for it .”

On April 19, 1865, he writes from Raleigh, declaring that “Rebel General Lee has given up the army of Virginia. The rebel General Jo[h]nston has given up so we heard. . . He is in camp about 25 miles from here. If he did we will walk there in less than twenty 4 hours. ” And finally, at the end of April, he reports the “glorious news [that] the war is over. General Jo[h]nston surrendered to General Sherman yesterday .” Barber was mustered out on June 7 and returned home on June 28, 1865.Letters written in both pencil and pen, both of which have faded in some instances. With toning, foxing, and creasing as expected.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB