Archive of the Carter Family of Hawaii and Massachusetts, Featuring Content Regarding Royalty, Island Events, and the Hawaiian Counter-Revolution

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

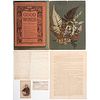

Archive of the Carter Family of Hawaii and Massachusetts, Featuring Content Regarding Royalty, Island Events, and the Hawaiian Counter-Revolution

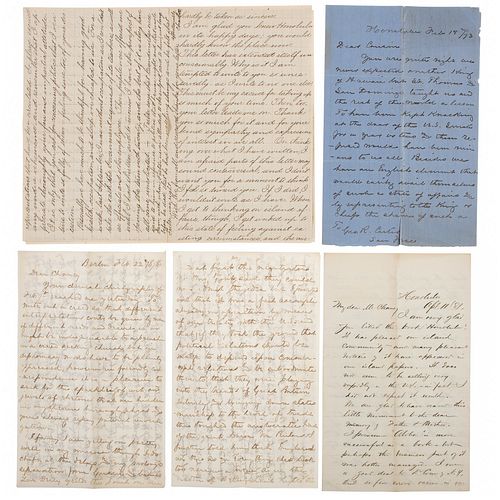

Comprehensive family archive of over 50 pieces of ephemera, including 34 detailed letters describing the Hawaiian monarchy, the possibility of annexation by the United States, the Hawaiian Counter-Revolution, a smallpox outbreak, and general island life, 1873-1895. Also with pressed foliage, genealogical records, a CDV by Gurney of New York, and newspaper articles, including a letter to the editor of a Hawaiian newspaper attacking the overthrow of the monarchy by “Annexationists,” ca 1895.

Correspondence is primarily between the Hawaiian branch of the illustrious Carter family to cousins in Massachusetts, where Puritan colonist and family progenitor Rev. Thomas Carter settled in 1635. Most of his descendants remained in Massachusetts, concentrated in Woburn, Lancaster, Leominster, and Charlestown, with the notable exception of Captain Joseph Oliver Carter (1802-1850), a trader of Chinese commodities to Hawaii and California. Captain Carter immigrated to Hawaii, where he married his wife, Hannah, another ex-patriot. The couple had six children, and two of their sons, Joseph Oliver Carter, Jr. (1835-1909) and Henry Alpheus Peirce (H.A.P.) Carter (1837-1891), would figure prominently into Hawaiian politics. The younger Joseph Oliver worked as a journalist, financier, and diplomat, serving in the Hawaiian legislature. H.A.P Carter was a partner at shipping firm C. Brewer & Co., working mainly with Hawaiian sugarcane plantations to refine and ship sugar to the United States. An outspoken advocate for free trade to reduce tariffs, H.A.P. became involved in island politics and was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs by King David Kalakaua in 1876. His wife, Sybil Augusta (“Gussie”) Carter (1843-1906), daughter of American missionary Gerrit P. Judd (1803-1873), who later served as cabinet minister to King Kamehameha III. H.A.P and Gussie write the majority of the letters offered here to their distant cousins, Rev. George Leonard Chaney (1836-1922) and his wife, Caroline Isabel (Carter) Chaney (1845-1925). Other authors include Gussie’s brother Albert Francis Judd (1838-1900), who served as Chief Justice of the Hawaiian Supreme Court; missionary David Belden Lyman (1803-1884); and Charlotte Adelaide Carter (1860-1936), the daughter of Joseph Oliver Carter, Jr.

Charlotte Carter writes what is arguably the most dynamic letter of the collection, in which she describes the wounding and death of her cousin Charles L. Carter, son of Gussie and H.A.P., in the Battle of Diamond Head on the first day of the Hawaiian Counter-Revolution, January 6-9, 1895. Charlotte writes to Cara Chaney just a few days later to share the unfortunate news: “What the trouble was we didn’t know, having no idea of the collection and preparation of armed forces for this revolt. . . after some talking among the men who had been called out on the veranda [at Charles’s house]. . . [they] rushed for their arms and started off. . . Charles was crouching with his rifle. . . ready to fire, when he was fired upon and struck, and his position explains the downward course of the ball that was. . . found later in the abdomen, the wounds being above. . . As yet the government troops have not succeeded in finding and routing the others, though they are reported to have seen them here and there.”

Another fascinating letter from Charlotte details the life of a Royalist family living under the provisional government, written to Cara Chaney just prior to Charles’s death on the eve of the Counter-Revolution, January 6, 1895. Her brother, Oliver, worked at a bank, and Charlotte relates that “some people tried to make trouble for him. . . when the employees were notified of the wish of the manager that they should take the oath of allegiance to the ‘Republic’ (which included a promise never to assist or encourage the restoration of the monarchy), he didn’t take it. How could he?” She expresses frustration at the corruption of the provisional government or “P.G.” and writes ominously that it “may take much longer to see the peaceful resolution and settlement of things. . . judging from the past two years. We conceded that a change was necessary. . . that all things were not as they should be, but that change might have been brought about through the Queen herself in a legitimate way. . . it has certainly brought the country into a worse condition than ever before. I know that the importance of a weight guarantee for the safety of large amounts of foreign money invested here has been urged by the P.G. as another excuse for their action, but not one sugar plantation from Hawaii to Niihau – with the exception of Mr. Spreckles’ [Claus Spreckels, influential German-born industrialist] – is the result of foreign capital. All these sugar people have made their money right here under the monarchy, aided by the treaty which was due largely to the understanding urged in Washington - but not made public here – that the islands should some time be given over to the United States. . . if the character of Hawaii’s kings and queens had been different, the government might have commanded more confidence. Would that it had!” With additional descriptions of the Counter-Revolution’s impact on Hawaiian congregational churches, the unscrupulous election rigging by the “sugar people” in the last election, and the social ostracism of Royalists.

The development and negotiations of trade and annexation treaties are carefully documented in the correspondence of Gussie and H.A.P. Carter during his service to the monarchy as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Despite his American heritage, H.A.P. was opposed to annexation, as revealed in letters written as early as 1873. He writes to his cousin, George R. Carter of Leominster and San Jose, California on February 18, 1873, expressing his distaste for American diplomacy with Hawaii: “We never expected another King of Hawaii but Sir Thomas and San Domingo taught us and the rest of the world a lesson. To have him kept knocking at the door of the US Senate. . .would have been ruinous to us all. . . when the United States gets through quarreling over railroads &c. they may build up a foreign policy and I think it will embrace the acquisition of these islands unless in the meantime some other nation will help us out.” Later, in December 1876, H.A.P. shares the details of the formation of a new Hawaiian cabinet ministry, including his own acceptance of the foreign office: “[The former] ministry resigned, not bad men, not all weak men, but did not pull together. Their dissensions were operating badly, demoralizing the native element in the gov’t – the King sent for us. I wanted to help him make up a gov’t which left me out, but Hartwell would not go in without me and a gov’t with any other man as Attorney General is at a disadvantage. . . they said I had a large personal following in the Kingdom which would be dissatisfied. I insisted the King should give up ‘personal government’ and let his ministers ‘serve the king but govern the country,’ that he should make a Premier and let him be responsible. He agreed, [and] Smith and Hartwell asked me to take it but I declined to do so so long as I was actively engaged in private business, but said I would take the Foreign Office. . . so here I am ready to assume the Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Serene Highness the Grand Duke of Pumpernickel…”

In this role, H.A.P. and Gussie hosted a number of lavish state dinners, as detailed in a letter from Cara to her uncle during a visit to islands: “Henry gave a dinner. . . there were 54 guests [including] the King, Queen, all the foreign diplomats, and it certainly was a brilliant and elegant affair. There were three American generals who looked well in their uniforms, a Russian captain and man of war, also an English one.” The post also required H.A.P. to travel extensively to Great Britain, France, Germany, and Washington, DC, where he was stationed semi-permanently for some time. He met with Otto von Bismarck, then the Foreign Minister of Prussia, as well as the Earl of Derby and other European politicians to negotiate treaties on behalf of the Hawaiian government, but was frequently stymied by nepotism and opposing blocs. From Berlin on February 22, H.A.P. writes to George Chaney that he has “reason to believe the British gov’t have warned the German gov’t against allowing the principle I wish to establish that may make what commercial treaty we please with America so long as we give no European country any advantage over other[s]. . . they were playing into the hands of Great Britain entirely and bringing down statesmanship to the level of trade. . . diplomacy moods have to be plainly expressed.” He later confirms that he has established a “treaty with Germany which leaves us free to send sugar and get shoes free of duty.”

By the mid-1880s, H.A.P.’s exhausting travel schedule begins to wear on Gussie, who confides to both George and Cara that she is unhappy. She joins him in Washington but is displeased by the weather and her social obligations and longs for her “Sweet Home” in Hawaii. A perceptive husband, H.A.P. alludes to plans to resign his office in several letters, noting that marriage is the “ultimate treaty” and that it is “a man’s duty and right to be with his family.”

Descriptions of the islands themselves are vivid and capture the unmatched beauty of the Hawaiian landscape, including the “slippery, worn lava stones” observed on a horseback ride through the Kaliki Valley and a summer trip to Waikiki, “where the rollers come clear in & they would all dive and swim through the foam of the surf and let it break over them.” Also with content related to patronage of American artists visiting Hawaii; tensions with the Chinese immigrant community; commentary on the political administrations of US Presidents Arthur and Cleveland; family dynamics; and encounters with David Graham Adee (1837-1901), a lawyer and author from Washington dispatched to Hawaii by the State Department for coverage of island life. - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB