Archive of Lois DeFee, Burlesque Star

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 12, 2015 - Jun 13, 2015

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

The lot consists of one of DeFee's costumes (no headpiece), photographs (unfortunately none in the costume), letters, news clippings, music written for her performances, a jewelry box with a few items in it and many "jewels" from old costumes, and other miscellaneous items.

The costume was worn for a number called the "Ziegfield Strut." It consists of skirt, bustier, pants, sleeves (2 separate), undergarments, all with clear square rhinestones among turquoise sequin swirls.

The lot includes a few personal items: a velvet jewelry box on brass feet that contains just a few items: a pair of wood guitar earrings, a pair of Champaign-in-ice-bucket earrings and a pair of Martini glass earrings; a pin “Lois;” a bar pin; a faux pearl necklace, cut glass necklace, hair comb, large bobby pin. There are also 4 large tubes (prescription bottles) of the “rhinestones/crystals” that came from, or were going onto, costumes – various shapes and sizes, some with holes, some needing adhesive.

A dark red velvet-covered box contains a necklace with a note in Lois’ hand: “Arthur Treacher, Aug. 20, 1941, Starrs Birth.” (a gift from Arthur on the birth of her daughter).

An Ascot (brand) green suede clutch with “L. de F.” in gilt on flap (empty).

There is a compact, 4.25 in. diameter, with mirror, powder and puff intact. Note in Lois’ hand: ”1940 Compact Borrowed for Roper Wedding.” (Possibly Fred Roper, who had a “Company of Wonder Midgets”)

Notes and letters include several holiday cards: Hector de Ayala, Ambassador of Cuba (2); John Astor (printed sig.); The Durantes – Jimmy, Margie and CeCe, printed names. Other notes from Earl Wilson (New York Post); Sammy Kaye (1910-1987); Hank Henry; Lili St. Cyr.

A few personal papers, including a form for rent increase on a NYC apt., rejections for sponsorships, envelopes (empty) for airline tickets, and her passport, with several extra photos. The passport was from 1962 (she was pretty much retired by then), and does not have any stamps in it. Her birth date is listed as 1 Aug. 1918 in Missouri. Her daughter is listed as her emergency contact. There is also a cover letter that accompanied the contract for the World’s Fair in New York (not the contract). A “theme book” titled "Lois Erlanger," appears to record her memories later in life. The "theme book" includes notes from a European tour; a list of people with the header “They went on to Bigger stages"; a section labeled “Comics | Straights"; and a large section labeled “Girls,” referencing names such as Dimples Delight, Winnie Garrett, Zorita, and many more.

A briefcase with the lot contains some commercial sheet music, but most importantly, it contains manuscript scores for Conductor, Piano, 1st Trumpet, 2nd Trumpet, 1st Alto, 3rd Alto, Tenor Sax, Trombone, Bass, Drums with pieces written for DeFee. Most were written by Manny Blanc, except Glamazon (by Wm. Riley). They include: Music for “G” String, Fee’s Weirdee, Haitian Strip, The Blues, Voodoo, Chino, andHouri. Glamazon is missing in the Conductor and Drum folders, but all the rest are complete. A few have duplicate copies, and when that occurs, usually one is torn, dirty, and probably was unusable in a club. All with “Lois DeFee” in the upper right corner. The instructions on the music are great. Forget adagio orlargo or legato: these are marked “Slow and Dirty,” Slow and Bitchy,” “Slow and Weird,” “Slow and Houri” (you sound it out!), etc.

Manny Blanc’s other papers were donated by his daughter to NYPL. According to the biography that introduces the collection, Manny was born into a family of musicians on Aug. 17, 1914. Shimele (Samuel) Blank was a composer and musician and owned a music store on Second Avenue, so Manny was surrounded. His brother played as did several cousins. In addition to popular music, Manny composed symphonies and ballets, string quartets, brass, as well as playing with orchestras such as Tommy Dorsey’s. While recovering from surgery, he acquired a paint set, and began a new creative career. In a couple of internet searches we conducted, his name is associated with painting more readily than music.

There are many other items: a signed first edition of Zito’s Dogs (“To Lois / a few sophisticated “doggies” from Zito.”) Vincenzo Maria Zito (1900 – 1966) moved to Palm Beach in 1953. (He might have been a neighbor.) A single nude photo in a leather folder. A menu from Dave’s Blue Room, “Where New York Meet Broadway;” on front and back are collages of performers who have been to Dave’s – Lois’ photo is circled on the front.

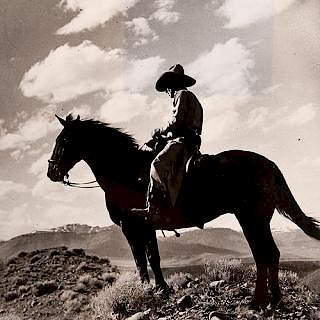

The lot includes 4 photographic binders, one of which contains many publicity photos, series of photos demonstrating portions of her act in a club, and views of clubs and theaters promoting "Lois DeFee." The second binder contains 27 publicity stills of Lois in different costumes, all by Bruno, Hollywood. The third binder appears to contain mostly personal photos, capturing Lois with friends, including several men, some of whom may have been husbands. The fourth binder also contains mostly personal photos, some labeled in Lois’s hand.

One loose item is the cover of the National Police Gazette from 1942 with a page on Lois (p. 31) glued to the back of the cover. One observation: “Miss De Fee is one of the major attractions of Broadway musicals and plays many return engagements. She is clever enough to understand the value of publicity and ingenious enough to devise methods of securing it. Teamed with a midget, Miss De Fee attracted much attention not so long ago. She evidently believes in the old wheeze that it was “better to have loved a short man, than never to have loved a tall.” The midget marriage and sign in front of the theater are obvious examples of her skill in coming up with publicity.

From the collection of photos, it is obvious many of her friends were boxers/wrestlers, etc. In early burlesque the format was truly “variety,” and often the show ended with a boxing or wrestling match. And Lois started out as a bouncer. So, in a newspaper clipping from June 8, 1973, “Lou Nova challenged six-feet plus Bdwy. Amazon bouncer emeritus Lois DeFee (in the wake of the Bobby Riggs-Margaret Court hoopla) to fight – in the ring; Lois, now Mrs. Milton Erlanger of Miami could’ve licked Lou when he was young!” (“Helen Carroll’s Clipping Service Strikes Again!”) A second newspaper column mentioned the same challenge. Was Lois afraid of being forgotten? Or did she really not have anything to do with THIS publicity stunt?! [The Riggs-Court tennis match was the predecessor to the televised Riggs-Billie Jean King “Battle of the Sexes.”] It is almost too bad the fight never happened. At one point Lois thought about training as a fighter (in her bouncer days), and her friends offered their help, but she decided it would entail too much work, and admitted in one interview that she was basically lazy. (We doubt that. It took a lot of stamina to be on the road for months and do three and four shows a night.)

There is a copy of Flirt, April 1952 with a two-page spread on Lois (pp 32-33). “She’s the biggest attraction to hit burleycue in many years!...This teasin’ torso-tosser is wowin’ the peelin’ circuit! No wonder! That’s a lotta gal, eh boys?” There are two copies of the program for the 1968 Miss USA Pageant program held that year in Miami; Lois DeFee is listed as the Sales Director. She was also well-known for her work with local humane societies in Florida. Many of the items in this group are newspaper clippings. They span everything from ads for the various clubs and announcements of her appearances, to columns in which she got publicity (in a 1949 Walter Winchell column, he notes that Lois de Fee… “has been fired before but never for such a reason: Just got canned because the night club ceiling was too low!”). Some record the passing of friends.

There were also a number of interviews among the clippings and articles cut from periodicals. In one interview she talked about burlesque performers changing their names. Lois went on to say she would never do that, as she had built up some name recognition (“branding” in today’s marketing). She noted that some of her more conservative relatives had asked her to change it, and when she refused, THEY changed THEIR names. Their loss. This clearly was a woman of character, who was a character (in the best sense). We wish we could have known her, and she should not be forgotten.

Born in a small town, either Missouri (passport) or Texas (Goldwin, 2006), depending on the source, Lois DeFee lost her parents early and was raised in Texas by an aunt (her father’s sister) and uncle. It was not a happy situation, and Lois began trying to run away at the age of four. She finally succeeded at 13. In her early attempts she headed west; this time she went south, and ended up in Miami. One club owner was recruiting showgirls for a stint in Cuba. Lois recalls: “Brass monkey me. I walked right in and got the job.” (Goldwyn, 239) But she was tall and probably did not appear to be barely a teenager. She would advertise her height in her heyday as a burlesque queen at 6 foot 4 inches, or thereabouts. She was a bit shorter in stocking feet, but not much. The show played in Cuba for several months. The producer discovered Lois’ lack of dancing talent, so they had her stand as a nude statue in the back of the line or parade slowly across the stage – elements that apparently became part of her later performance style. She also made lifelong friends in Cuba, including the ambassador and his wife.

When the show left Cuba, it was to open in Miami. Lois missed the train stop and continued to New York. She contacted a friend of another acquaintance from Cuba, and he gave her a job as bouncer at The Dizzy Club. The job grabbed attention, including that of Walter Winchell, who also would become a friend. It was Winchell who later dubbed Lois the “Eiffel Eyeful.” In 1933, she moved to Leon & Eddie’s club on 52nd, also as a bouncer. She later recalled that she never really “bounced” anyone, but served more as a hostess and occasionally calmed potential problems probably just by being a distraction. If she came up to talk to you, you probably forgot what you were going to fight about.

In 1939, she got a job at the New York World’s Fair in the Amazon exhibit as “Queen of the Amazons.” The title stuck, and occasionally was modified to “Queen of the Glamazons.” It was here that Al Minsky recruited her for a featured act in one of his venues. The only catch was that she would be doing a striptease. She confessed later that she had no idea how to do one, but went to the clubs and watched over a dozen in a week. She was smart and a quick study, and for $400 a week, she would develop her own style and performance. Her style was so sophisticated and stately that she had a large following of women as well as men. Lois was married a number of times. The citations vary from five to eight, with seven being the most common. In one of the interviews in the collection of papers in this lot, the interviewer asked how many times she had been married, and she quipped something to the effect of “often enough to make my sex life legal.” The “Lois stunt” that is cited everywhere is her marriage to midget Billy Curtis (3’ 2”). Some have speculated that it was all prearranged, because the marriage was annulled within a day or two – by the same judge that married them.

The term “burlesque” is derived from the Italian burla, a joke, mockery, parody. The meaning has expanded since its early literary forms, and the form was applied to music and theater. American burlesque theater derives from English burlesque, and it is generally traced to the arrival on American shores of Lydia Thompson and the “British Blondes.” They were an immediate sensation, with long lines for tickets even before they arrived in 1868. Eventually British and American burlesques went their own ways, with the American form incorporating elements of minstrel shows and vaudeville, and later, cancan from France. The British form evolved into musical comedy by the turn of the 20th century.

American burlesque hit its peak by 1900 and continued as a major entertainment form through the 1930s and into the war years. The focus was increasingly on exotic dancing and comedy. As Ann Corio and Joseph DiMona note in “This Was Burlesque,” (1968: 39-40):Burlesque was like a rocket that got off the ground in 1900 when Sam Scribner formed the Columbia Circuit. Along the way there were some of the brightest sparks ever seen in show business – sparks that issued forth from a group of comedians whose names read like a roll call of a Hall of Fame of humor. Among them were W.C. Fields, Will Rogers, Bert Lahr, Ed Wynn, Joe E. Brown, Leon Errol, Buster Keaton, Joe Penner, Eddie Cantor, Bobby Clark, Al Jolson, Jimmy Durante, and Abbott and Costello.

Burlesque was the breeding grounds for these great comics. It gave them a stage, an audience, and a chance to develop the acts, mannerisms, pantomime, or whatever made them famous. Al Jolson sang his first song in a burlesque house. Joe E. Brown was part of an acrobatic team; he had never said a word on stage or tried to be funny until he entered burlesque.

…In his autobiography, [Joe E.] Brown wrote:

‘The public’s low opinion of burlesque today has caused more than one prominent star to soft-pedal his (or her) humble beginnings in the field. I am much too grateful for the things I learned in burlesque to belittle its importance in my story….’

As far as the “girls” went, the transition from dance to strip was gradual and subtle. To advertise their attractions, many of the “Burlesque Queens” had a trademark – Sally Rand’s fans, Zorita’s snakes, other “girls” used doves or parrots or even exotic furs, Lois DeFee (6’ 4”) and Ricki Covette (6’ 8”) had “stature.”

Even though it was in its heyday, burlesque took a number of “hits” in this time period – two world wars, a depression, and, worst of all, Prohibition. Then many of the performers, especially actors and comedians, began moving to film and television – good for a wider audience, not as good for burlesque. By the 1950s it became strictly a strip show, and incorporated what many of the earlier stars saw as coarser elements, including what many people identify with striptease, the “bump and grind.” When asked about modern striptease, Lois once quipped: “Modern day girls are nude, lewd, and get screwed.” (Goldwyn, 244) Not so in her day. This was seldom part of early burlesque, and when it came to be expected, many of the stars, including Lois and Zorita, who (it must be admitted were also aging) retired. The earlier performances were more sensuous, more suggestive.

Many of these stars of the stage are now gone, and many forgotten for their earlier roles. Only those who made it “big” in film or television tend to be remembered, which is a shame in many ways. These were the pioneers of mass entertainment. These were the ones who made the “transition.” In many respects they also crafted the forms that entertainment took in the second part of the 20th century. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB