American Artist and Critic Eugene Benson, Personal Correspondence, Ca 1860s-1870s

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 26, 2020

Cowan's Auctions is delighted to present the June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography Auction, including 55 lots devoted to the African American experience, over 175 lots dating from the Civil War Era, and more than 60 lots documenting life in the American West. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

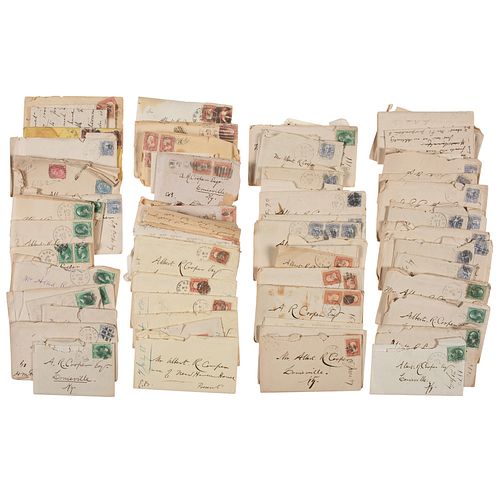

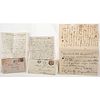

American Artist and Critic Eugene Benson, Personal Correspondence, Ca 1860s-1870s

Lot of approximately 77 letters with original covers, all but two written by Eugene Benson (1839-1908), member of the National Academy of Design, art critic, and painter; remaining letters written by Benson's mistress Henriette Malan Fletcher (1830-1917). Addressed to Benson's first cousin and childhood friend, Albert Rudolph Cooper (1840-1917) of Louisville, Kentucky. Nearly all letters 4pp+ with a large number 8pp+ in length. Bulk of the collection spans January 1863 - May 1871, a pivotal time in Benson's literary and artistic career. Includes references to significant American painters including Winslow Homer, to Benson's art criticism and prominent post-Civil War literary publications, and to many of the leading intellectuals and editors of the day. Also notable in the collection is the extensive discourse related to Benson's step-daughter, writer Julia Constance Fletcher (1853-1938), who wrote under the pseudonym "George Fleming." An extraordinary archive with deeply personal and descriptive content, while simultaneously illustrative of a new wave of influential mid-nineteenth century American artists and art criticism.

Benson's writing is emotional, philosophical, and at times brutally honest, perhaps because he writes to his cousin who, by every indication, is a close friend and confidante. Albert R. Cooper's mother and Benson's mother were sisters, and their children were raised alongside one another in New York. Federal Census records show Cooper working as a bookkeeper in NYC in 1860, but by 1863 when this correspondence commences, Cooper was in Louisville. He would reside there for the remainder of his life.

Benson forged a path that stood in stark contrast to his cousin's business pursuits, an observation that Benson himself often notes in these letters. Eugene Benson was born in Hyde Park, New York, though thereafter little is known about his early life. Presumably, he exhibited substantial artistic talent as a young man. Before his twentieth birthday, Benson had already pursued studies at the prestigious National Academy of Design and studied portraiture in the studio of painter James H. Wright (1813-1883). Benson worked alongside such notable painters as Winslow Homer, Sanford Gifford, William J. Hennessy, and Eastman Johnson. In 1862, Benson was elected as a member of the Academy. His journalistic pursuits emerged during this time as a way to supplement his meager income as a painter, though it would soon evolve into Benson's primary means of subsistence.

Uniquely intimate and candid, this archive offers fascinating insight into the often competing aspects of Benson's life, particularly his work as a painter and critic, his affair and later marriage to Henriette Malan Fletcher, and his struggle to support himself and his family while pursuing his artistic passions. The earliest letter in the collection, 15pp in length, is representative of Benson's writing throughout the archive. Writing from the "North Tower Jan 5th 1863," an exuberant Benson states that his year "closed splendidly" having sold a picture for $100, received four commissions, and $24.00 "with my pen on the Round Table for one week's matter." The $100 painting was "Fading Days" which according to Benson received high compliments from "[Richard Henry] Stoddard the poet and Bayard Taylor." Benson notes that it was Stoddard who recommended him to write for the Round Table, that he found out who prevented him from becoming a critic for the Commercial, and that the critics of the New Path attacked him "most personally," telling Cooper: "I have twice, on former occasions exposed their pretensions, and in last week's Round Table I return to the charge - Of course they hate me - and many men in the profession view me with distrust and dislike me for my criticisms, or because I have ignored them. I am determined to do my duty and be fearless. If I have to go to the wall it shall be in a good cause." As he inevitably does, Benson then turns towards more personal matters. "I am in hopes Violet will soon be on to see me. I miss her dreadfully. Ah Albert we are committed to each other, body and soul, and I thank God that I possess and am possessed by her."

Mrs. Henriette Malan Fletcher, known to Benson and others as "Violet," was the great love of Benson's life. At the time this correspondence commences, Violet remains married to Rev. James Cooley Fletcher, though she is regularly keeping the company of Benson. Mrs. Fletcher would eventually leave her husband and live with Benson, a saga which plays out vividly in Benson's letters from 1863-1871 and which resulted in Benson's near complete expulsion from polite society. On June 20, 1863, Benson tells Cooper that he is enjoying life in NYC, "and my art papers [are] daily attracting more attention from the best men. I am also getting into controversies with the Pre-Rap[haelite]'s which I enjoy, and above all still have the companionship of the woman I love... I have just returned from Violet....Every night finds me at her room, sitting in an easy chair reading or talking while she sews and her little girl reads. We are all perfectly happy together, and I love the girl almost as much as Violet."

The "little girl" that Benson loved was Julia Constance Fletcher, one of two children born to Violet and the Rev. Fletcher. Affectionately known to Benson and Violet as "Dudu," Julia is frequently referenced in Benson's letters throughout the decades long span of the archive. It is clear that Benson was a loving father-figure to Julia during the tumultuous end of her parents' marriage, and that he remained so throughout her life.

Benson remarks on numerous occasions that Julia was often a model for his portrait work. While Benson's work as a writer fills the greater portion of his correspondence, his work as a painter seemed to have been his true passion. Paintings referenced in the archive include "Fading Days," "Fisherman's Daughter," and "The Anatomist." On May 18, 1863, Benson described "The Anatomist" writing in small part: "This week I take up my large picture of 'The Anatomist' with which I expect to make a reputation worth having....The anatomist whom I represent is a man of about thirty-five living in the latter half of the seventeenth century, when the study of anatomy was pursued with great ardor and in secrecy by men, because of the sentiment against desecrating the human body. For so it was believed. I have my anatomist in an attic to indicate his poverty, his removal from the world, and the loneliness of his awful studies...."

It seems Benson would, in some ways, be destined to share a similar fate of his subject in "The Anatomist." Benson's letters from 1863-1871 abound with discussions of the difficulties he faced as a writer and the ways in which his relationship with Violet, which was viewed as scandalous by most in society, impacted his prospects. He writes of Parke Godwin, editor of Putnam, and of James Thomas Fields and the Atlantic Monthly. He writes of the Galaxy, Appleton's, Putnam's and more. He writes of the blistering critiques of his writing and of his paintings, of his struggle to paint and to publish, and of the desperate state of his finances. Unable to earn a living and at odds with many of his contemporaries, Benson becomes increasingly disenchanted with American life, literature, and his own isolation. On October 3, 1869, Benson writes "my most striking articles never reach the public - only those which are confirmed to the average sentiment of publishers and editors - O how gladly would I lay down my pen ... I never have written for any other purpose than to make money and discipline my own faculties by the mental exercise...But I am a native of a country which is favorable to the writer and difficult for the painter...."

By May 1868 Violet and Julia had essentially been thrown out of their Massachusetts home by Rev. Fletcher, and were residing publicly with Benson. After moving to New Haven, CT with Violet and Julia in July of 1868, Benson and his "family" were not only physically removed from the city of New York but soon were ostracized from polite society. Julia would not, however, repudiate her mother, even going so far as to refuse an opportunity to live in Europe with her father. Adding to their woes was the departure of Violet's oldest child, Edmund "Eddie" Livingston Fletcher, from his appointment at West Point. His return home to Violet and Benson put yet another financial and emotional strain upon the couple. Benson's letters from 1868 through 1870 detail these family struggles, while also decrying false friends and the "malign influence" that results in nearly all of his articles being rejected. Benson notes solemnly though in a letter of February 14, 1870, that it is "Dudu" upon whom the whole ordeal is the most trying, adding in a later letter that she "has become a noble and beautiful girl."

The correspondence of 1871 represents a Benson who, despite his circumstances, is deeply content with his home life yet remains at odds with his contemporaries. He notes on February 18, 1871, "...a successful journalist is a man who rides on the current of opinions, which is odious to a man of convictions, or even a man with a love of opposition. The principles of modern society are such as forbid us to think in a sense contrary to the ruling powers - and it is difficult and sometimes foolish to do so...." After a visit with his cousin in Louisville, Benson is preparing for a trip abroad where he expects to live and write for a few years. He marries Violet before he sails as noted in his letter of May 14, 1871: "I was married yesterday morning. Violet is now my wife as the world understands a wife."

Nearly twenty years elapse in the collection with the final three letters in the archive dating to the 1890s. Benson, now an ex-patriate living in Venice with Violet, remains the devoted husband and step-father. In a 15pp letter written from Venice on April 19, 1894, Benson exudes parental pride in his step-daughter. Julia Constance Fletcher's play "Mrs. Lessingham" has just opened at the Garick Theater in London and Benson shares news of her accomplishment with his long-cherished correspondent: "We have new cause of great pride and joy in our George Fleming - and I fancy she is at the end of the long, weary way of trial and uncertainty, God bless her."

Largely forgotten after his departure for Europe and at times dismissed by later American literary historians, Benson was nonetheless a significant figure in his day who achieved considerable renown. The letters offered here provide unvarnished context to his incisive criticism as well as incredible research potential. Cowan's was unable to locate any records indicating that Benson's manuscript material has come to auction previously, and only a small number of institutions are known to have his manuscript material in their collections.Nearly all letters in good condition and easily legible.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB