Ambrose M. Hite, 33rd Virginia Infantry, Stonewall Brigade, Civil War Archive

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 21, 2014 - Nov 22, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

Ambrose M. Hite, 33rd Virginia Infantry, Stonewall Brigade, Civil War Archive

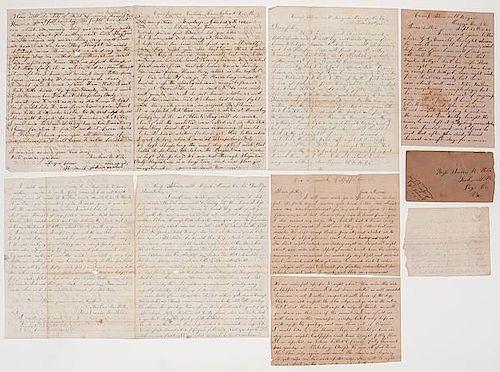

7 items.

Ambrose Martin Hite (1843-1921) was a 19-year old native of Page County who was serving as a private in his local militia company, the Page Grays (Co. "E" of the 97th Virginia Militia,) when General "Stonewall" Jackson ordered the Valley militias disbanded in the spring of 1862 and their men transferred into Confederate service.

Hite enlisted in Co. "H," 33rd Virginia Infantry of the "Stonewall Brigade" with most of the Page Grays on April 8, 1862, replacing casualties suffered by the regiment at Kernstown. He served with the 33rd Virginia through the major engagements of the war in the East, including the famous Valley Campaign and Gettysburg, until the Stonewall Brigade was all but wiped out in the Mule Shoe at Spotsylvania. Taken prisoner of war on May 12, 1864, Hite was immediately sent to the Ft. Delaware POW camp, where he remained for the duration. He took the Oath of Allegiance after the war, on June 20, 1865, and was released the same day.

These seven letters written by Hite to his family date from April to December of 1863. The first letter, dated April 2, 1863, from Camp Winder, Caroline Co., VA, notes that Four more of our boys were let out of the guardhouse this evening. They were sentenced to be shot, but were reprieved, going on to name presumably local boys from Page Co.

June 8, 1863, finds Ambrose writing his father: On a march, Culpepper Co. Va. Speculation among the Stonewall Brigade was that the concentration of forces at Culpepper Court House meant a return to the Valley, but Hite says I am afraid we will have another Manassas scrape, but I only hope we will whip the Yankeys and run them out of Virginia. Little did they realize that this was the start of Lee's second invasion of the North, which would culminate at Gettysburg. Hite gives such precise information of the marches of the Stonewall Brigade in his letters that you can follow them on a period road map.

A letter dated June 29, 1863, contains great content regarding the Gettysburg campaign, as Hite contrasts the enthusiastic reception of the Marylanders of the Army of Northern Virginia with the sullen hostility of the Black Dutch of Pennsylvania once they crossed the border. He notes that Pennsylvania is a rank abolition state... The people are mostly Dutch through this country, and the people are very ugly here... We are about four miles from Carlisle Town. We are twenty two miles from Harrisburg, which is the capital of this state...We have had no fight with the Yankeys since we crossed the Potomac. After a detailed description of the farmland and crops, he continues Some of the people here don't believe that Gen Jackson is dead. They think this is one of his raids...Our men are not treating the citizens here as bad as the Yankeys treat you all, by right smart...We are taking their horses and some of their waggons. We also take corn, flour, shugar, and molasses. We are sending lots of flour back to Virginia... We get plenty to eat now.

The next letter, with unstamped cover, is dated September 12, 1863, from Camp Stonewall Brigade, Orange Co. VA. Ambrose tells his sister of the news regarding some of their relatives serving in the Stonewall Brigade: I heard from John Hite and David. John is dead and David was left at Gettysburg to wait on the wounded. Don Weekly brought the news, he was left at Gettysburg wounded, he was paroled and sent home.

Hite's 4pp letter of December 5th relates the adventures of the 33rd Virginia in the Battle of Mine Run. He describes how the Stonewall Brigade was marched from Orange Court House towards Mine Run to meet the advance of Meade's army: When we were marching along, we heard cannonading in our front. After we had gone some three miles the yankeys attacked our division in the rear. (This was General Henry Prince's 2nd Division of III Corps.) We halted then, and sent out skirmishers. The skirmishers commenced firing very rapidly directly. A line of battle was now formed, and then we was ordered forward. We then started with a yell down through the woods. We then soon came in contact with the yankeys. We drove the yankeys twice from their position. We quit fighting after dark. After this attack (at Paynes Farm,) the 33rd Virginia took its place on the Confederate defensive line, building up their breastworks for the next three days. We expected to have a big fight there, but the yankeys was afraid to attack us in our fortifications... I do not think old Meade will pester us any more this winter.

The last letter is actually a letter to his father on one side of the page, and a letter to his sister Fannie on the other. Dated December 13, 1863, Hite notes that casualties have hit the regiment hard, with only five men in his mess now. He mentions again that he would really appreciate a box of provisions from home, and hopes his father can come to camp and visit. It had been a year since the 33rd had left the Valley, and Hite had been home only two days since then.

In all, a nice collection of letters from a Valley boy who went to war with Stonewall Jackson and lived through it all. - Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB