Abraham Lincoln ALS Written During the Lincoln-Douglas Debates

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Nov 21, 2014 - Nov 22, 2014

Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

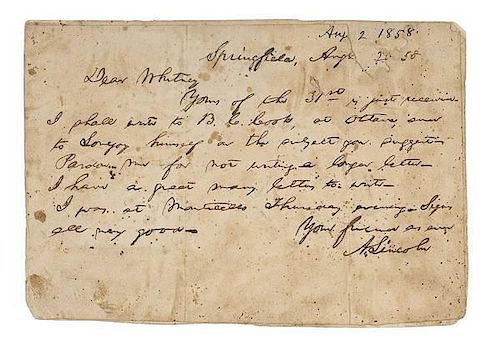

Abraham Lincoln ALS Written During the Lincoln-Douglas Debates

1p, 5.25 x 7.75 in., Springfield [IL], 2 Aug. 1858. Note entirely in Lincoln's hand: Dear Whitney, yours of the 31st is just received. I shall write to B. C. Cook at Ottawa and to Lovejoy himself as to the subject you suggested. Pardon me for not writing a longer letter as I have a great many letters to write. Your friend as ever, A. Lincoln.

While not a supporter of slavery, neither was Lincoln an abolitionist. He had some sympathy for the capital investment slaves represented, and knew its abolition would jeopardize the Union. Early in his political career he supported plans that would phase out the practice gradually, attempting to preserve the Republican moral high ground and the Union simultaneously.

Opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which gave voters the right to choose whether slavery would be allowed in a new territory, resulted in 1854 in the formation of the Republican party. However, then, as now, the party encompassed more conservative and more radical factions. Owen Lovejoy was part of the more radical abolition faction. His brother, Elijah, also an abolitionist, was killed in Alton, Illinois, trying to protect a new press brought in to replace one (of many) that had been destroyed by pro-slavery residents. Elijah is often cited as being the first martyr to freedom of the press.

Being something of a "natural" politician, Lincoln tried to avoid the extremes, but, like all politicians, he occasionally offended one faction or another. His "House Divided" speech, delivered earlier in the summer of 1858 when Lincoln was selected to oppose Stephen Douglas for his Illinois senate seat, was thought too radical by many in the party. In spite of their different viewpoints, Lincoln certainly respected and trusted Lovejoy as a person, and the two become friends along the way.

The letter to which Lincoln was responding was from Henry Whitney, a fellow Republican. In his letter, Whitney warned Lincoln about the political dangers of getting close to radicals such as Lovejoy. Elements in the Republican party were threatening to support Douglas's Democrats in many local and congressional races. As alluded to in this note, Lincoln passed the information along to Burton C. Cook, another Republican and lawyer in one of the most prestigious law firms in Ottawa, IL, which just a few weeks later would be the site of the first of seven debates with Douglas. In his note written the 2nd of August, he tells Cook: ...[T]here is a plan on foot ... to run Douglas Republicans for Congress and for the Legislature,...if they can only get the encouragement of our folks nominating pretty extreme abolitionists.... Please have your eye upon this.

In this response to Whitney, Lincoln implies he will keep Lovejoy at arm's length, but his exact response to Lovejoy has been lost. Lovejoy's response to Lincoln, however, survives, and in his letter of 4 August, he ends with: Yours for the ultimate extinction of slavery.

Over the months of August through November 1858 Lincoln and Douglas engaged in a series of debates. Most centered around slavery, with Lincoln emphasizing the immorality of the practice and Douglas supporting "popular sovereignty" - the basis of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Although Lincoln lost the election, the debates thrust him into the national spotlight, and ultimately gained him the party nomination for president two years later. In this sesquicentennial year of these historic debates, (and, of course, an election year) we might remember that occasionally losses lead to greater victories.

Found inside a book purchased at a Florida flea market, this letter was featured on a segment of the PBS series History Detectives, Episode 10, 2007.Toned, foxed and laid down on cardboard. This note was overwritten (where it "needed" to be darker) in dark ink for the purpose of creating a facsimile for Whitney's published correspondence with Lincoln.Condition

- Shipping Info

-

SHIPPING. At the request of the buyer, Cowan's will authorize the shipment of purchased items. Shipments usually occur within two weeks after payment has been received. Shipment is generally made via UPS Ground service. Unless buyer gives special instructions, the shipping method shall be at the sole discretion of Cowan's Auctions, Inc.. Cowan's is in no way responsible for the acts or omissions of independent handlers, packers or shippers of purchased items or for any loss, damage or delay from the packing or shipping of any property.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB