A Memorandum of Butler's Expedition on the Mississippi River, Civil War Diary and Letter Archive of G.G. Thwing, 30th Massachusetts Infantry, DOD

About Seller

6270 Este Ave.

Cincinnati , OH 45232

United States

With offices in Cincinnati, Cleveland and Denver, Cowan’s holds over 40 auctions each year, with annual sales exceeding $16M. We reach buyers around the globe, and take pride in our reputation for integrity, customer service and great results. A full-service house, Cowan’s Auctions specializes in Am...Read more

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

| $1,000 | $100 |

| $2,000 | $250 |

| $5,000 | $500 |

| $10,000 | $1,000 |

| $20,000 | $2,500 |

| $50,000 | $5,000 |

| $100,000 | $10,000 |

About Auction

Jun 22, 2018

Cowan’s American History: Premier Auction, scheduled for June 22, 2018 is comprised of early photographs, documents, manuscripts, broadsides, flags, and more dating from the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, Late Indian Wars, World War I and II and beyond. Cowan's Auctions dawnie@cowans.com

- Lot Description

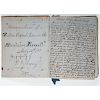

George G. Thwing Civil War diary (Jan – Nov 1862), 96 pages, 5.75 in x 7.25 in., self-titled A “Memorandum of Butlers Expedition on the Mississippi River!!” July 12th /62.” Faint writing on the front of the diary reads “State House, Baton Rouge” and the rear cover bears the inscription “Day Book ! Yay Book !!!!”. Accompanied by Thwing family correspondence spanning 1861-1866. The family correspondence consists of 89 total letters, of which 40 are written by Private Thwing during his enlistment, another 13 are written to Private Thwing, and an additional 35 are to/from other Thwing family members. Diary and correspondence intertwine providing a detailed account of Thwing’s service including references to the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, the occupation of New Orleans under General Benjamin “Beast” Butler, and the Battle of Baton Rouge.

George G. Thwing (ca 1841-1862) was born in Massachusetts to Gardner H. and Jane Littlefield Thwing. He was the eldest of two children, the younger being his sister Eliza Jane who was five years his junior and who features prominently in the family correspondence. George’s father is listed as a blacksmith residing in Cambridge, MA, in the 1850 US Census, but neither George nor his father Gardner appear in the 1860 Census. Military records indicate that George was a 21-year-old clerk when he enlisted as a Union Army Private for three years’ service on December 5, 1861. However, the family correspondence indicates that he was, in fact, a printer. On September 14, 1861, in the only letter in this collection written prior to his enlistment, George writes to his sister Eliza that “…All is excitement about the War…a great many of the printers working at the ‘Riverside’ have gone to the seat of war.” Presumably this is a reference to Cambridge’s famous “Riverside Press” which was founded and operated by printer Henry O. Houghton, and was the forerunner to Houghton, Mifflin & Co. George may have worked at the Riverside Press Building in 1861, or perhaps he was engaged as a printer in another location. His letter continues, “Business at my Printing Office is ‘rushing,’ Mr. Miles has started three or four works, within the last week, so that I shall have plenty of work…”

On December 22, 1861, George mustered into “E” Co. of the 30th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, which was raised by General Benjamin F. Butler. Known originally as the “Eastern Bay State Regiment,” the MA 30th was organized at Camp Chase in Lowell, MA, and it is here that Thwing’s diary commences. “The regiment I joined was quartered at Camp Chase, Lowell, Mass. and remained their for about a month; the Mass 30th, Maine 12th, two companies of horse took the cars for Boston, after arriving at Boston all of the men were formed into line and marched to Long Wharf and embarked on board of the Steamship Constitution; the steamship remained anchored close to the Wharf for about a month.” Due in part to an ongoing feud between Massachusetts Governor John Andrew and General Benjamin Butler with respect to whom had the authority to raise militia within the state, the soldiers of the Eastern Bay State Regiment were on board the Constitution for an extended duration.

Conditions were less than comfortable on board the Constitution, a situation relayed by Thwing in his characteristically descriptive prose style. “Co. E the company I belonged to was quartered in the lower hold of the ship a miserable pace for a human being to live in, while we were quartered there we had nothing to eat but muddy coffee and hard bread and salt junk, the place our company were quartered was full of body lice. The officers got for their food, turkeys, chickens, and everything that could be had in markets. The privates would get better food if they were in the State Prison than they do here.”

By mid-January, the steamer Constitution would sail for Fort Monroe, VA, to begin the next phase of its journey, an event noted in Thwing’s diary, “Monday 14th[ Jan 1862] – Cold. Early in the morning anchor was raised, in about an hour after the steamship sailed for Fort Monroe, the weather was very rough, the ship anchoring two or three times while going there…” Thereafter, Thwing’s near daily entries describe the weather and arrival at Fort Monroe on Monday the 21st of January. He continues with accounts of drills, weather, meals, and free time. On February 2, the 30th made its initial departure from Fort Monroe headed for its final destination, Ship Island, where General Butler was preparing a force for the capture of New Orleans. Thwing recounts that the steamship was forced to turn back to Fort Monroe once to assist the disabled gun boat Vienna and then again after its second departure it sailed back for more coal. Finally, on the 6th of February, the Constitution would at last make its way to the open ocean bound for the Gulf. On February 9th he notes seeing the Florida Coast and the Florida Keys, on February 10th he notes that they sail into the Gulf of Mexico and pass a number of lighthouses with land being clearly visible. Finally, on February 12th, 1862, Thwing arrives on Ship Island.

Located off the Mississippi Coast approximately 60 miles west of New Orleans and even closer to rebel strongholds including the ports of Mobile, Biloxi, and Gulfport, Ship Island was of significant strategic importance to the Union. The island was a base for movement against the Confederates and for patrolling the entrances to the Mississippi River and Mobile Bay. New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy and a major Confederate port, was a coveted prize, and George Thwing’s Massachusetts 30th Regiment was one of nearly 30 infantry regiments ultimately stationed on Ship Island as preparations were laid for “Butler’s Expedition” to capture New Orleans. Writing from Ship Island to his sister Eliza on February 21, 1862, George describes the island: “Ship Island is a desolate place much so than where any other Union troops are quartered….this island was a favorite watering place for the rebels, the[y] came here from all parts of the south when the gun boats captured the island it contained about three or four hundred houses and a large Hotel, and a very large light-house which they entirely destroyed when they left the island, so you can see that we are right in the midst of the rebels. They cruise about the island almost every day, but are very careful not to get within distance of the guns belonging to the fort or the frigates or gunboats lying at anchor close to the land for our protection…”

From February 12 through mid-April 1862, Thwing remains at Ship Island, engaged primarily in training and fatigue duty. His diary entries during this time deal oftentimes with the difficulty of training and the extreme heat to which he was not accustomed, “Friday [February] 28th Plst. [Pleasant] – Early in the morning all four of the regiments and the Rangers, three Batteries, the whole amounting to over 5,000 men were formed into line and marched all over the island through the loose sand. It was positively the hardest thing for me to keep in the ranks the perspiration actually ran in a stream off my chin, the hot sun pouring down on my face all the time…” Writing to his father from Ship Island on April 11, 1862, George describes a difficult drill, “Our Company have been practicing a part of this morning with ladders, they are the largest ladders that I ever saw they being used to scale fortresses etc. we are drilled with them almost every day, we have to lash them together (and at the count ‘one’ take the two quickly upon our shoulders, ‘two’ go ‘Double quick’ down to the beach again and then quickly raise one end of it in the air one of the men going up to the top of it so as to look ahead...) the ladders…were about twenty feet long, being about wide enough for three persons to go up the ladder side by side…”

Thwing’s diary entries during this time also frequently note the rain which came down in "pailfulls," anticipation of payment, visits with fellow soldiers who were friends from home, the ever-present difficulty presented by blowing sand, arrivals of new regiments, and details of military activity in the area. “Wed [February] 19th Plst – One thunder shower during the day. The Steamship left Ship Island yesterday afternoon. A small craft was captured yesterday by the New London, containing 60 men and armed with two or three guns, it was fitted out in New Orleans, and was cruising about in the Gulf waiting for the Constitution; it mistook the frigate ‘Niagra’ for the steamer and fired two guns into it, but it astonished the rebels when the frigate opened its portholes and gave them a whole broadside, the fire tore both masts, all of the rigging away leaving it looking a mud scow the rebels were immediately ironed and taken aboard of the Niagra, after sinking the scow.”

Union forces peak strength on Ship Island came in April 1862 when more than 15,000 men were stationed there. Thwing’s regiment prepared to depart for the next phase of the expedition, and on April 14, 1862, the 30th finally received orders to pack up for departure. The next day, his company ate breakfast, marched to the wharf, and went on board the steamship Matanzas. Two days later, the expedition left Ship Island and sailed toward the mouth of the Mississippi River, anticipating the inevitable battle that was to come.

Thwing’s diary is notable for the its regular descriptions of troop arrivals and departures, troop strength estimates, and for his detailed accounts of the comings and goings of vessels of all kinds with specificity to type of vessel, the name of vessel, and when a commander of importance is on board. On April 18 while aboard the Matanzas he writes, “We anchored last night at a place called the South Pass, where there was lying at anchor the frigate Colorado, one of the Blockading Fleet, it carried 35 or 40 guns. There was lying close by an English Frigate of 30 guns & an English Sloop-of-War. Early this morning the Matanzas took in tow the ship North American and started up the river, not before saluting the Colorado, which they returned. The Matanzas passed a small place on the right-hand side called Pilot Town formerly belonging to the rebels. But now belonging to the U.S.; the Stars & Stripes could be distinctly seen floating from one of the tallest buildings; it is now used as a hospital for sailors and soldiers….” The next day Thwing witnesses from downriver one of the critical battles en route to seizing New Orleans - the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. “Sat. April 19th – Plst – After casting anchor about five miles from the fort, men could see Porter’s Mortar Fleet bombarding Fort Jackson, a part of the fleet was lying at anchor close by. About dark a gun boat came down the river, alongside of the Matanzas, and gave the news to the Gen. (the Saxon being side of us at the time) The news was that Com. Porter’s fleet consisted of thirty vessels, besides a large number of war vessels, frigates, sloops-of-War, and gunboats. At about 9 o’clock in the evening a large fire could be distinctly seen back of the trees, and underwood in the direction of the fort, burning brighter and brighter as the darkness increased, it burned five or six hours before it went down any….” The fort was not on fire as Thwing initially suspected, rather “The large fire I wrote of yesterday proved to be a large rebel raft, covered with pitch pine and fiery combustibles, this was set fire and sent by the rebels at Fort Jackson down the river they intending to set the fleet on fire, if possible, but the swift as luck would have it took it ashore amongst the mud and bushes, where it stayed for a while….”

Thwing provides additional descriptions of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, before proclaiming in his diary on the 25th, “Good News!! Fort Jackson Silenced Yesterday Morning, and a part of the fleet with the Mortar Boats have gone up to New Orleans.” Noting on the 28th of April that Forts Jackson and Philip surrendered, he goes on in subsequent entries to describe his journey up the Mississippi River. He describes passing beautiful plantations and Forts Jackson and Philip. He notes the shorelines full of dropping willows, wildflowers, wild animals, "a few white folks," and "negro wenches jumping up and down, waving their dress, and trying to cheer." He then writes about an interaction with a slave, one of many such interactions with African Americans that he references throughout the diary. While his new vessel Lewis was taking in coal “a colored man 80 years of age without hardly any clothing on came down to the boat, and he told a pitiful story, his story was that he had been a slave for nearly fifty-one years, that he had had since he had been in bondage five or six masters; that his family, a wife and four children had been taken from his arms and sold under the hammer, which was thirteen years ago, and every since that he did not care what became of himself…”

On May 3, George Thwing arrives in New Orleans. His most evocative descriptions of the mood in the city are to be found in his letters to his father and his sister Eliza. On May 5, 1862 (letter erroneously dated April then May 5, 1861) George writes to his father that he has safely arrived in New Orleans but that the Union soldiers are less than welcome, “After our company were landed we formed into line after loading and caping [?] our guns, (in case the mob attacked us we wanted to be prepared) and escorted an artillery company the 6th Mass Battery to the Arsenal which is situated in the centre of the city, the streets for a greater part of the way were lined with the Mob who sassed us and cheered for Jeff Davis (but they are more civil now).... There was in front of the Arsenal a mob of about twenty thousand men stretched along as far as the eyes could reach, but there being three or four artillery companies with the guns all loaded and ready to fire at any moment they did not show much fight, except using their voices in cheering for Jeff Davis.” That same day, George writes Eliza that, ”I see sights here all day long too numerous to mention Pretty girls too, one in particular being the handsomest that I ever saw, the city is filled with females but there is a scarcity of males….The Southern report here is almost all lies, such as Washington is taken, Gen. McClellan surrendered with fifty thousand men.” On June 9th George recalls in a letter to his father one of the most infamous moments of Gen. Butler’s occupation of New Orleans – the execution of New Orleans resident William B. Mumford for tearing down and defiling an American Flag. “Yesterday there was a rebel hung in New Orleans, by Order of Gen. Butler for insulting and hauling down the American flag from the flagstaff.”

As a member of a Pioneer Company, Thwing was soon detached from New Orleans and quartered in the village of Carrollton to fix telegraph wires north of the city along the railroad. On May 28 he notes in his diary that “A Large quantity of contraband arrived in our quarters to-day, having run away from their masters, two of the Captain took as cooks, they being used to the business.” Later entries reference the numerous women of color who were busily engaged in selling pies, cakes, and other desirables to Union soldiers encamped in the area.

In his diary entry of June 14th George Thwing writes that “My limbs and shoulders are pain me considerably today; they seem to be getting more worse than better.” This is a reference to “rheumatism” which seems to have plagued George since before the war. First referenced Dec 14, 1861, in a letter to his father, George notes that he is getting along well in camp but “My shoulder was very lame at first while carrying my rifle … It has done my lame knee a great deal of good since I have been here.” His “lameness” would prove to be an ongoing source of difficulty and, along with an onslaught of other maladies, would sideline him from active military duty for much of the remainder of his service. When the 30th arrived in Baton Rouge on June 16th, Thwning would not join the rest of his regiment in preparing for combat operations at Vicksburg, instead he would remain behind at the Baton Rouge State House which was a resting place for soldiers unfit for regular duty: “… as soon as the steamer touched the levee the Capt. Received Orders not to land his men, but send his men that were not fit for duty up to the State House, Frank, myself, and two other with Sar. Spear landed and walked up to the State House.”

The Baton Rouge State House was immensely impressive to George Thwing. He writes in multiple letters and in his diary of its magnificence, and of the impressive George Washington statue on its grounds. George continues to write in his diary while recuperating from rheumatism and a bad leg sprain in Baton Rouge. His diary relates the tension that infused the city citing several examples of false alarms as the city anticipated attack. On July 5th "alarming intelligence reached the city that all pickets were driven in and “…men and women were running thither and thither in the excitement. The gunboat opposite the State House cleared their deck and prepared for action…” After a period of nervous unrest, it was determined that it was all a hoax. George also writes of those being discharged to go home from his regiment, of his unwavering desire to receive his own discharge, and of the ongoing guerilla activity in the region as on July 16th, “A Captain and two Lieutenants of the guerrelas, was captured in this city day before yesterday. All three of them were captured in their residences, all of their property was destroyed, they were sent to N. O.s to pay their respects to Butler.”

On August 5th, the anticipated Confederate attack on Baton Rouge at last commences, and Thwing provides a vivid recounting in his diary. “This morning at 5 o’clock the rebels under Gens. Breckerridge and Lovell with a force of 8,000 men attacked the federal troops one camp (14 Maine) they took entirely by surprise; and had fired two volleys into them before they had formed a line of battle. At five o’clock the fight on both sides raged furiously. Gen. Williams was killed at the commencement of the Battle, we had about 4,000 men on our side, the Mass. 6th Battery lost 3 guns, but they were captured by a gallant charge of the Indiana boys…Breckinridge had his arm shot off and was taken prisoner. Capt. Kelly of the famous Zouaves, was killed. I saw crowds and crowds that were wounded. At the beginning of the engagement reinforcements were sent after at New Orleans. Lieuts. Hows’ body has been recovered. The evening the enemy came in with a flag of truce to bury their dead. Col. Dudley said that he was proud of his regiment, that they acted bravely; he also said that if it had not been Capt. Nims Battery, our side would have lost the day, the Battery fired the fastest of any battery on the field and raked the rebel ranks down by hundreds.”

The remainder of Thwing’s diary consists largely of details related to his rapidly deteriorating health, the medical review process, and his unwavering desire to attain a discharge. Letters home typically reflect the same. Writing to Eliza on August 12,1862, from the Marine Hospital in New Orleans, George writes of his expected discharge: “I have at last good news to write to you. I have been sent down to New Orleans, to the Marine Hospital, and Gen. Butler has given orders to the Medical Directors here (at this hospital) to send home all men that are incapable of duty besides the wounded; one of the Directors had a talk with me this morning, and he took my name down for a Discharge, and said that I would be sent home very soon, Only think of it! You cannot tell how happy I am….Tell father that I have found out what home is now, and that he will find in me an altered son! I would give almost anything to see him.”

Yet to his great consternation, George was not destined for a discharge. An August 20 exam by the surgeons tasked with determining which men would receive a discharge is little more than a cursory discussion. George writes in his diary that “…the surgeon asked me what ailed me and I told him, that was all the examination that I got; he then said ‘O you will do’, A very great examination indeed, but I shall not be discouraged if I do not get it this time….” Deemed fit for duty, Thwing departs Baton Rouge on August 23rd with his regiment for Camp Parapet at Carrollton only to enter the Marine Hospital in New Orleans once again on September 1st. He tells his father on September 6th, “I have been examined by the ‘Medical Board’ twice and they said, laughingly, that I was playing off; I have made up my mind to leave the Hospital tomorrow morning and limp up to the regiment which is quartered about four miles from the Hospital…The Medical Board consists of three surgeons, the Head one is named Doctor Brown and he is the one that said I was playing off, he belongs to New Orleans, and was here before the Union troops took possession of the city – he is a regular Secession rascal, and an ugly man, and tyrant, he has charge of this Hospital.” Still unable to receive a discharge from the army, Thwing was discharged from the Marine Hospital on September 6th to return to his regiment.

The situation in camp is difficult for Thwing and all the men of the 30th. Writing to his father and sister and in his diary, he details the illnesses that ravaged the regiment and deplorable living conditions. “Sunday Sept 14, 62 – Camp Williams New Orleans …Dr. Holt of my regiment told me that I was used up, and would be of no further use while in the army, he excuses me from duty every day….There is not more than two hundred men that do any duty at all in this regiment they being sick or dead, the fever and ague is the prevailing disease, the men that have the shakes, lay in the sun outside of the tents and shake themselves almost to pieces, it is an awful disease and I hope that I will not have it.” In his diary he is increasingly despondent. “Monday Sep 22nd-Today is my birthday and a miserable birthday it is. I have got the worse kind of Diarrhea, the chronic, a great many soldiers have died here with that complaint…. Thurs. Sept 25th…I have got the Chronic Disease very bad nothing but blood and matter comes from me…. Friday Sept. 26th – It rained very hard all day today, some of the tents being flooded with swamp water, outside of the tents it was over shoes in mud & clay. It is awful for a sick man.”

By early October, Thwing’s health has declined to an extent from which he will not recover. “Dear Sister Eliza, I am very sick, it is with the greatest effort that I write this letter, since the 22nd of last month (my birthday) I have been failing very fast, the Doctor has done me more hurt than good, last night I fainted away while coming back to my tent from the necessary, I had to be brought back to my tent. My complaint is the chronic Disease, Rheumatism, and I have had the fever….” Dysentery and “swamp fever” are decimating Thwing and his regiment in large part because “…All the water that we have to drink here is ‘Byou water,’ (water running through the swamps). It almost turns a mans stomach to taste it, but it is all we can get here, this is positively the truth.” Thwing encapsulates the situation with these words to his father on October 22nd, “…there is nothing but sickness here.” His last entry in the diary reads simply "Saturday Nov 1st."

Letters home fill in the gaps that are left between the end of Thwing’s diary and his death of disease on December 20, 1862. Reduced to a skeleton, unable to move on his own, and suffering immensely, George sends several more letters to his family noting on December 13 that he has been removed from the hospital in New Orleans and resides now in a private residence. The letters are no longer written by George who, at this point, is too weak to do so himself; rather the letters are written by the women of the private household in which he will take his last breaths. Offering a fascinating glimpse into healthcare and society during the war, letters in the collection describe how George became acquainted with a group of New Orleans women who visited soldiers in the hospital. He appealed to one woman to take him to her household to recover, and she did.

George Thwing lived out the few remaining days of his life in the home of Mr. and Mrs. F.A. Woolfley under the care of the Woolfley family and extended family. Francis Augustus Woolfley was a young Swiss immigrant who married a Louisiana native and was employed at the Office of the Fire Alarm and Police Telegraph in New Orleans. Letters reveal that the Woolfleys sent for the best doctors in the city to assist with George’s care, and provided him with comfort and companionship until his last breath. It was Mr. F.A. Woolfley who wrote to George’s father on Christmas Day 1862 notifying him of his son’s death, “Mr. Thwing, You have no doubt heard before this of the serious illness of your son; and of the circumstances attended with his removal from the Hospital at the US Barracks to my house, where we took him, being assured by Surgeon Fowle of the 30th Massachusetts Regt that he was likely to die if kept in the Hospital, but if a family could nurse and care for him properly he would recover, but alas: I must now kindly ask, that you prepare to hear the mournful truth – Your son is no more – he has gone from this world – never to return – never to be racked by disease and pain as poor fellow he was…” This letter would not reach Gardner H. Thwing in Cambridge as at this time George’s father had already undertaken a journey to New Orleans to care for his son and secure his discharge. Arriving in New Orleans just after his son’s death, the letters indicate that George’s father was welcomed like family into the Woolfley’s home. In the months and years to follow, the Wollfley family, particularly Mrs. Woolfley’s sister Miss Florence A. Flanders, would continue to correspond with Eliza and Mr. Thwing in a series of warm and familial letters included in this collection.

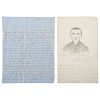

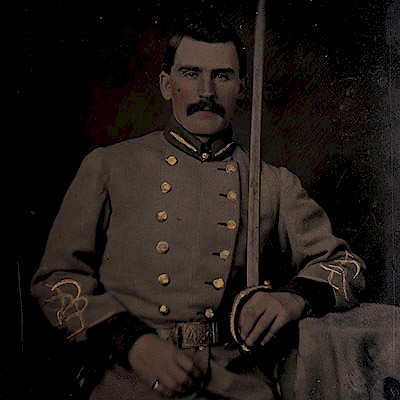

George’s death was noted in The Cambridge Chronicle, and a written copy of his obituary is included in the collection stating in part: “He was a printer; and worked in this office for several years. He was a young man of much promise beloved by all who knew him, and the news of his death will be read with sadness. Thus has fallen another young patriot – The victim of an unholy rebellion.” Also accompanying the collection is one 3.25 x 3.25 in. pencil image of George Thwing. Carefully illustrated on the top of a June 6, 1862, letter to Eliza, the picture is noted to have been drawn by “Artist, Carl Astrom, of Sweden.” Carl Astrom of Salem, MA, was a private in the Massachusetts 30th. A small assortment of miscellaneous newspaper clippings round out the collection.

The letters in this collection are in good condition with the expected wear and folds given age. Most letters do not include the original covers. The diary does maintain its original covers, however, the spine has worn almost completely away. While the diary remains intact, the binding is in such condition that pages are beginning to come away from the spine. In both the letters and the diary, Thwing’s handwriting is typically clear and legible.Condition

Eliminate the Hassle of Third-Party Shippers: Let Cowan's Ship Directly To You!

If you'd like a shipping estimate before the auction, contact Cowan's in-house shipping department at shipping@cowans.com or 513.871.1670 x219. - Shipping Info

-

Buyers are required to pay for all packing, shipping and insurance charges. Overseas duty charges are the responsibility of the successful Bidder. Be aware that for larger and/or valuable items, shipping charges can be substantial. - If there is no shipping amount on listed your invoice, you will need to make arrangements to pick up or ship your purchase through an alternative shipping company. Our shipping department can be contacted at 513.871.1670 (ext. 219) or email shipping@cowans.com. - Shipping charges include insurance for your order while in transit. If you have private insurance we will adjust your charge to include only packing and shipping. - Please allow 14 – 21 days after payment to package and ship your purchase as carefully as possible.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB