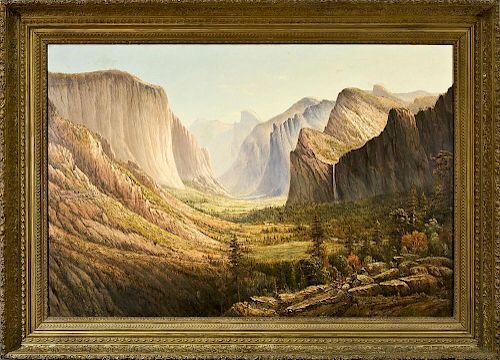

James Everett Stuart (1852-1941), Yosemite Valley

About Auction

Mar 16, 2017 - Mar 30, 2017

Bidsquare info@bidsquare.com

- Lot Description

For more information, email: gallery@hirschlandadler.comYosemite ValleyOil on canvas, 40 1/4 x 60 1/4 in.Painted about 1886A landscape painter associated with the San Francisco art scene during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, James Everett Stuart drew inspiration from the scenery he encountered in diverse locales such as Alaska, Canada, Mexico, and Maine. However, he was best known for his depictions of his adopted state of California. As noted by a writer for the New York Times, Stuart “painted many parts of California before it became thickly settled and had made many sketches and paintings of Donner Lake, Lake Tahoe, the Yosemite, the high Sierras, the valleys and meadows near the coast, and missions and adobe shacks” (“James Stuart, 88; Landscape Artist,” New York Times, January 4, 1941, p. 13).Born near Bangor, Maine, Stuart was the son of Daniel and Lydia Stuart. (Contrary to numerous published accounts, Stuart was not the grandson of the famous portraitist, Gilbert Stuart). In 1860, his family relocated to northern California, settling on a 200-acre ranch near the town of Rio Vista, on the Sacramento River. Stuart began drawing at an early age and shortly after moving to the rugged West, he created his first painting, using materials discarded by local fishermen who had just painted their boats. (See James Everett Stuart, “Outline of a Brief Autobiographical Sketch Written During the Year 1924 by the Late James Everett Stuart,” typescript, California History Section, California State Library, Sacramento, California, p. 1. For additional information relative to Stuart’s life and career, see Edna Hughes, “Genius of the Peaks: Re-examination of the Work of James Everett Stuart,” Antiques & Fine Art 7 [September–October 1990], pp. 85–86, and Barbara Lekisch, Embracing Scenes About Lakes Tahoe & Donner: Painters, Illustrators, & Sketch Artists, 1855–1915 [Lafayette, California: Great West Books, 2003].) In the ensuing years, he continued his artistic endeavors in secret so as not to annoy his father, who needed him to help herd sheep on the ranch. After painting farm wagons for a few years, Stuart moved to Sacramento to work in a carriage shop, where he eventually became the foreman. Intent on pursuing a career as a professional artist, he spent his Sundays studying under the portraitist David Holmes Woods. On weekdays, he sketched along the banks of the Sacramento River before heading to work.In 1877, after traveling to Oregon and Washington, Stuart settled in San Francisco, where he honed his skills as a portraitist under the tutelage of Benoni Irwin and painted a likeness of the poet, novelist, and playwright, Joaquin Miller (California State Library, Sacramento). He then enrolled in classes at the San Francisco School of Design, where he studied under the landscape painters Virgil Williams and Raymond Dabb Yelland until 1897. During this period, Stuart also fraternized with a coterie of older, well-established artists that included Thomas Hill and William Keith, who, like Williams and Yelland, shared his interest in depicting western scenery. A member of the prestigious Bohemian Club, Stuart also became friendly with other major California landscape painters of his day, including Jules Tavernier and Julian Rix.From 1881 to early 1886, Stuart sketched and painted in Oregon, selling his work to merchants and other well-to-do visitors to his Portland studio. He also made summer trips to Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, where many of his sketches were purchased by fellow tourists. (For Stuart’s Yellowstone scenes, see Peter H. Hassrick, Drawn to Yellowstone: Artists in America’s First National Park, exhib. cat. [Los Angeles: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, 2002], pp. 100–14, 237.) Upon returning to California in March 1886, he made a brief visit to his family’s home, after which he traveled to the Yosemite Valley, in the western Sierra Nevada about 150 miles from San Francisco. That Stuart should be drawn to this locale is not surprising, for Yosemite had been a gathering place for artists since 1851, attracting leading painters such as Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran and photographers such as Carleton Watkins, all of whom took great delight in the valley’s natural beauty and panoramic views. Stuart’s cohorts––Hill, Keith, and Williams––had been visiting Yosemite since the early 1860s, and Raymond D. Yelland painted there as well. Aptly described as the “Niagara Falls of the West Coast,” Yosemite appealed to artists attracted to grandiose wilderness settings that, in their unspoiled beauty, evoked a sense of the sublime (Kate Nearpass Ogden, “Sublime Vistas and Scenic Backdrops: Nineteenth-Century Painters and Photographers at Yosemite,” California History 69 [Summer 1990], p. 134).During his visit to Yosemite, Stuart made sketches that served as preliminary studies for his large-scale oils, among them Yosemite Valley. (Stuart painted Yosemite subjects well into the early 1900s.) In this instance, he has depicted the “Tunnel View,” a magnificent vista that visitors encounter upon entering Yosemite from the Wawona Tunnel. As our gaze moves from the rocky ledge in the foreground, we encounter dense pine forests flanked by two iconic natural rock formations, El Capitan (the Spanish term for “the captain” or “the chief”) on the left, and the aptly named Bridalveil Fall on the right, with its 620-foot plunge into the valley below. Another granite summit, known as Half Dome due to its peculiar shape (one side is sheer vertical rock face while the other three sides are rounded and smooth), can be seen in the distant middleground, enveloped in a delicate veil of atmosphere. (Other California painters drawn to this dramatic panorama included Thomas Hill, who portrayed it in his Yosemite Valley From Below Sentinel Done, As Seen From Artist’s Point [1876; Oakland Museum, Oakland, California]. Stuart’s painting is closely related, compositionally, to Raymond Dabb Yelland’s 1885 canvas Yosemite Valley [for an illustration, see https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/21446951_raymond-yelland-oilc-1885-yosemite-valley]. The same view is also represented in a drawing, executed in 1855, by Thomas Almond Ayres, one of the first artists to visit Yosemite [reproduced in Ogden, p. 136].)In its structured design and emphasis on topographical detail, Yosemite Valley reflects Stuart’s familiarity with the transcriptive realism of the Hudson River School, exemplified in the work of Bierstadt and Hill, as well as Yelland, who received his training at the National Academy of Design in New York during 1869–71. Certainly, the painting represents Stuart at his best, revealing his ability to evoke the grandeur and majesty of his wilderness subject, as well as its distinctive geological features. Moreover, it also attests to his skill in evoking nuances of light and air, a pictorial concern likely inspired by his contact with Yelland, who, having been exposed to the work of luminist painters such as Alfred Bricher while living on the East Coast, was highly regarded for his ability to paint sunsets. In Yosemite Valley, the rich greens and earth tones that dominate the foreground and the right side of the canvas are balanced and offset by the radiant pinks, yellows, and pale blues used to denote the sunlit slopes on the left and the far-off mountains and sky.In late October 1886, Stuart went to New York to deliver one of his Yosemite landscapes to Charles Pratt, the Brooklyn-based businessman and philanthropist who founded the Pratt Institute (1887). Seeking to enhance his professional recognition and expand his clientele, he decided to remain in Manhattan, establishing a studio in the Holbein Building at 145 West 55th Street. There, Stuart became friendly with George Inness (who visited Yosemite himself in 1891), a painter of evocative tonalist landscapes who is said to have given him advice and encouragement. He also met other painters associated with Tonalism, among them Alexander Wyant and J. Francis Murphy.In 1888, a large auction of Stuart’s work was held at the Bucken Galleries in New York. Two years later, he decided to return to the west coast, visiting Yellowstone and then Seattle, where he sold his work to well-known patrons such as the collector, Fred E. Sander. In 1891, Stuart spent some time in Tacoma, Washington, before going on to Alaska to paint landmarks such as the Muir Glacier and Mount Fairweather. In 1892, he settled in Chicago, where he spent the next two decades painting landscapes that were acquired by the likes of Marshall Field, the owner of the upscale department store that bears his name. During this period, Stuart made trips to Alaska in 1893, 1897, and 1903. (For this aspect of Stuart’s work, see Estill Curtis Pennington, Alaskan Art from The Juneau Empire Collection, exhib. cat. [Augusta, Georgia: Morris Museum of Art, 1997], pp. 12, 15, 34–37.)In 1912, Stuart returned to San Francisco for good, establishing the Stuart Galleries in the Rothschild Building at 239 Geary Street, where he was based until 1923, when he relocated to a new space at 684 Commercial Street. A prolific artist who is believed to have produced over 5,000 canvases, Stuart was skilled at marketing his work: between 1900 and 1924, he sold $765,060.00 worth of paintings, drawing his clientele from prosperous Bay Area businessmen who took pride in owning landscapes that captured the glories of local and regional scenery. During these years, he often painted scenes of dawn or dusk, imbuing his canvases with a “wonderful glow effect” created by dramatic color contrasts (Philadelphia Item, 1902, quoted in The Famous Collection of American Paintings by James Everett Stuart, exhib. cat. [San Francisco: Stuart Gallery, 1941], n.p.). Stuart (who never married) died in his gallery on January 2, 1941, after which his younger brother, Joseph, continued to operate the Stuart Galleries until August 1944.Stuart worked primarily in a realist style, although some of his later paintings were influenced by the bright colors and fluid brushwork of Impressionism. In his autobiography, he pointed out that in 1880, he started experimenting with painting on aluminum, going on to develop a method by which “pigments attach themselves and became like one with the metal, a process said to be impervious to the action of time” (Stuart, pp. 6–7). This was, he said, his “greatest accomplishment in art,” although, as noted in an obituary notice, it was his deftly rendered views of the West, “from the frozen mountains of Alaska to the sun-flooded missions of Mexico,” that brought him fame and fortune in the art circles of his day (Stuart, p. 7; “Stuart’s Grandson Dies,” Art Digest 15 [January 15, 1941], p. 8).APG 20422D.001 CDL JES20422D.001

- Shipping Info

-

STORAGE AND SHIPPING INFORMATION

As the Buyer, you are responsible for the pick-up or shipment of the property you have purchased.

As a courtesy, the Seller has made arrangements with a variety of third party shippers to provide shipping quotes for Buyers. Please note that shipping remains the responsibility of the Buyer, and we highly recommend getting quotes during any preview period for large, fragile or heavy items so you can consider the shipping costs before bidding. As set forth more fully in the Terms of Sale, under no circumstances will the Seller or Bidsquare be held responsible for items entrusted to a third party shipper.

Shipping small items by common carrier (UPS, FedEx, DHL or USPS): Each of the Sellers has engaged shippers to pick up several times a week. Once the Seller receives your payment and the completed shipping form authorizing the release of your property to the shipper, the Seller will add your lot(s) to the list for the next pick up. Shipping quotes will be included in the invoice.

Shipping larger items by freight (for example: furniture, bulky or odd shaped items): For items that exceed allowable dimensions or weight restrictions of UPS, Fed Ex and similar carriers, the Seller may provide assistance in arranging for delivery by freight. Please keep in mind that delivery of these types of items can be an expensive proposition, so you should consider this before bidding. Please remember that it is your responsibility to pay for all deliveries.

Pick up: Please check the Seller’s pick up policies and be sure to bring your own packing materials.

Removal of Property:. Regardless of whether you arrange to have your property shipped or picked up, all property must be paid for and removed from the Seller within 14 days of the auction. Storage fees are charged beginning on day 15. For more details see below and see our Terms of Sale. Neither the Seller nor Bidsquare is responsible for any damage or loss of property purchased but not removed from the Seller within 14 days of the auction. Starting on day 15 following the acution, the Seller may, at its sole discretion, remove the purchased Property to public storage at the Buyer’s risk and expense. All associated charges will be added to the total or subsequent invoice and must be paid in full before the Property will be released.

Property purchased and left at the Seller for 90 days or longer will be sold or donated for you, at the Seller’s sole discretion.

Frequently Asked Questions

May I use one check to pay for the invoice and shipping charges?

Yes. You will receive a combined invoice for the item that includes shipping charges.Will I be charged tax for picking up the item at the Seller?

An 8.875% New York sales tax will be added to your invoice if you pick up your property from the Seller. This tax will be waived if you have a resale number. You must complete the proper documentation in order to avoid the sales tax charge.Do I need to pay for insurance coverage for the items in shipment?

We highly recommend insuring your items for their full value during shipping. If you choose to waive the insurance coverage, we require a signed waiver from you stating that you accept full liability for any damage that may occur in shipment.What happens if my item is damaged during shipment?

It is a rare occurrence, but if your item arrives damaged, you must keep all packaging materials. Notify the Seller immediately. Take photographs of the damage to the box as well as the item. A representative from the shipping company will make an appointment to come and inspect the damage and begin the claim process.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB