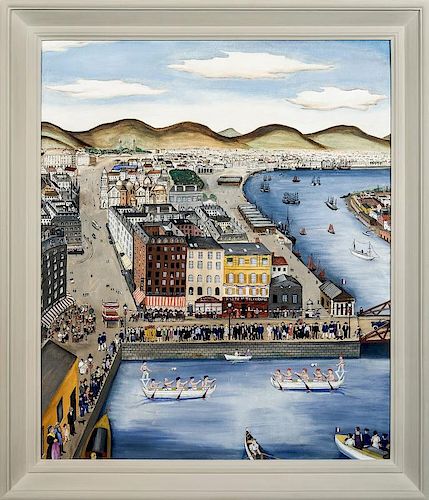

Hilaire Hiler (1898-1966), Le 14 Juillet

About Auction

Mar 16, 2017 - Mar 30, 2017

Bidsquare info@bidsquare.com

- Lot Description

For more information, email: gallery@hirschlandadler.comLe 14 JuilletOil on canvasboard, 30 x 24 3/4 in.Signed and dated (on brick wall, at lower left): hiler / 1928RECORDED: Louis Atlas, “Hilaire Hiler’s Paintings,” Paris Tribune, December 8, 1929 // Margaret Breuning, “Hilaire Hiler,” New York Evening Post, April 12, 1930, p. 3, as “14 Juillet” // Art et décoration 61 (November 1932), “Les Echos d’Art” supplement, p. V // William Saroyan, “A Note on Hilaire Hiler,” in Hilaire Hiler et al., Why Abstract? (New York: J. Laughlin, 1945), p. 34, as “The 14th of July” // Waldemar George, Hilaire Hiler and Structuralism: New Conception of Form-Color (New York: G. Wittenborn, 1958), n.p. // Hugh D. Ford, ed., The Left Bank Revisited: Selections from the Paris Tribune, 1917–1934 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1972), p. 202EXHIBITED: Ferargil Galleries, New York, 1928, Exhibition of the Recent Works by H. Hiler, no. 11, as “July 14th.” // Galerie Zborowski, Paris, 1929, Hilaire Hiler // New Art Circle Gallery, New York, 1930, Hilaire Hiler // Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, 1932, Hilaire Hiler // California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, California, 1945, Contemporary American Painting, as “The Fourteenth of July” // Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1968, Hilaire Hiler, no. 2, as “Quatorze Juillet,” lent by the California Palace of the Legion of HonorEX COLL.: the artist; to [New Art Circle Gallery, New York, 1930]; gift of Max L. Rosenberg to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, 1931–2012 (acc. no. 1931.31)Cosmopolitan in outlook and bohemian in spirit, Hilaire Hiler was a wholly curious and enigmatic personality in art, a highly refined and sensitive thinker who navigated among the modernist currents of Paris to produce a body of work entirely his own. Mostly identified today as an abstract painter, Hiler’s work evolved through several distinct phases, to each of which he brought his own peculiarly analytical insight and discerning eye.Born as Hiler Harzberg in St. Paul, Minnesota, as a young man Hiler moved to Providence, Rhode Island. After attending the University of Pennsylvania, Hiler received his only art instruction during a brief two-week stint at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts before moving to Paris in 1919. Hiler remained in Paris for about fifteen years. There, he studied at the University of Paris, the Institute of Psychoanalysis at the Sorbonne, the Cité Universitaire, the Académie Moderne, and at the Académie Colarossi. In Paris, Hiler exhibited his work at the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Indépendants. He also held classes in his Paris studio, the Atelier Hilaire Hiler, where the faculty included his best friend, Carl Holty, as instructor in watercolor and India ink. During his residence abroad, Hiler became closely associated with the avant-garde group that frequented the Jockey Club in Paris, including Ezra Pound, Man Ray, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Cocteau.Hiler began his career as a painter in Paris by painting panoramic city views in a carefully considered naïve style that owes as much to Brueghel as it does the Douanier Rousseau, whom he admired and to whom he was frequently compared. Hiler dubbed his style “Neonaturism,” later explaining of these works: “The objects perceived [must be] subservient to the basic design of the painting. This I tried to do by committing any required violence on their natural forms which I deemed necessary to force them into the design” (Hiler, Why Abstract? [New York: J. Laughlin, 1945], p. 21). His work found a ready market on both sides of the Atlantic, with such venerable galleries as Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, the Dover Gallery in London, and Ferargil Galleries in New York, giving him one-man shows in the late 1920s and early 1930s.Around 1930, Hiler made a brief visit to New York, and began painting Precisionist scenes of the urban environment. Hiler’s work of the early 1930s is yet more ordered and geometric. Buildings and other structures are presented frontally as pure color planes, often enlivened through the use of signage and lettering. In this respect, his work reflects an increasing interest in the abstract aspects of painting. In 1934, Hiler returned permanently to the United States, where he immediately involved in mural painting activities under the Works Progress Administration. He was named art director of the bathhouse building at the San Francisco Aquatic Park (the building is now the San Francisco Maritime Museum). By this time, his interest in abstract composition had expanded, and he became interested in the arts of Native Americans, incorporating these forms into his work. Over the course of the rest of his career, Hiler’s work became increasingly abstract, evolving in the 1950s into a style the artist termed “Structuralism.”A bon vivant and man-about-town, Hiler engaged in many professions in addition to his painting. At various times, he worked as a jazz musician, an ethnologist, a professor, a scenic designer, and a bartender. He was also the author of several books on art theory, including Notes on the Technique of Painting (1932), Color Harmony and Pigments (1940), and Why Abstract? (1945). His circle of friends included such notables as Henry Miller, William Saroyan, Sinclair Lewis, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Alexandra Exter, Constantin Brancusi, Amedeo Modigliani, Isadora Duncan, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Marcel Duchamp, Ernest Hemingway, Marc Chagall, and e.e. cummings. Although he never received the artistic notoriety of some of his artist friends, his work was exhibited regularly throughout his lifetime, and examples of his paintings are in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne, Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.Le 14 Juillet, painted by Hiler in 1928, is a superb example of the panoramic city scenes from his early naïve period. The painting depicts the city of Marseilles in southern France on Bastille Day, July 14, and it is accordingly a joyous celebration of everything French. While groups of people take their leisure in the outdoor cafes of the city, large crowds of people throng the waterfront to watch a water jousting contest—a quintessentially French sport that some say originated in the ancient Greek colony of Massilia (founded in 570 B.C), which later became Marseilles.Hiler showed Le 14 Juillet a number of times in the late 1920s and early 1930s in both Paris and New York, eliciting favorable reviews. Hiler’s overtly naïve style in works such as Le 14 Juillet was rightly interpreted as free-spirited expression of modern art. When the painting was included in a one-man show of Hiler’s work at the Galerie Zborowski, Paris, in 1929, a reviewer for the Paris Tribune opined:Hiler came to France ten years ago. The change from his native country to France overwhelmed him. He was (judging from the paintings) very much amused by the great French scene. The little bistrots and their clients, the life in the French seaports, the funny little streets, the wine and wood merchants, all appealed to him.He was not seeking to inspire anybody with his paintings. He did, however, wish to describe the joyous side of French life as he saw it. And he seems to have succeeded exceptionally well. He achieves unusual effect with his colors. . . . 14 Juillet is as good a canvas of French life as we have seen in a long time (Louis Atlas, “Hilaire Hiler’s Paintings,” Paris Tribune, December 8, 1929).In New York, the painting was part of a solo show of Hiler’s works at the New Circle Art Gallery, the important modernist gallery run by J. B. Neumann. A critic for the New York Evening Post observed:It is always [Hiler’s] ingenuous delight in places and people and panoramic scenes that attracts one first, such as the well-remembered “14 Juillet,” for example, and that makes it difficult not to associate him with the modern craving for naivete. Yet it must be confirmed that he does not appear to be in line as a successor to the worthy douanier [Rousseau], for the sophistication of his point of view and the technical surety of this painting are evident despite this amusing drollery on the surface. He is, obviously, first of all a painter, he is at home in his medium and delights in it. That is evident. He has a highly developed perception and a witty notation of the most negligible features of a landscape, street, or harbor panorama that gives his statement curious significance. That he is working to a new form of expression is evidenced by many of his new works (Margaret Breuning, “Hilaire Hiler,” New York Evening Post, April 12, 1930, p. 3).Once again the painting was back in Paris in 1932 for an exhibition of Hiler’s works at the prestigious Galerie Georges Petit. A reviewer for Art et décoration took note of the exhibition, singling out Le 14 Juillet and comparing it to the triumphalist Salon masterwork by the French painter, Alfred-Philippe Roll (1846–1919), Le 14 Juillet, 1880 (1882, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palais):The American Hilaire Hiler gives us scenes of the street, for example Quatorze Juillet, whose technique only shows distant relationships with the July 14ths of the late [Alfred-Philippe] Roll. But still it is the same desire to capture life in all its manifestations, to note carefully gestures and attitudes. There is an indication here that is not absolutely new, which would tend to have us believe that the joys of pure painting, color for color, seem too severe for many and are little more than delights for refined intellectuals. Hiler, so, like many other modern painters, observes. And observes with a keen eye, tireless, leaving nothing aside. . . . Hiler pays attention to every individual, every object, and makes them equal. This gives an impression of naivete, which almost becomes troublesome. For it is evident that the teller of these scenes is not naive, but on the contrary is of an amazing skill, almost virtuoso. Hence an imbalance: it’s impossible to surrender to pleasure, as is done in front of the image, full of genuine freshness, of a primitive. (Art et décoration 61 [November 1932], “Les Echos d’Art” supplement, p. V [translated from the French]).In 1945, Hiler published Why Abstract?, an important book on abstract painting and something of a personal manifesto. The volume contained two essays by Hiler as well as contributions from two of his close literary friends, Henry Miller and the playwright William Saroyan. In his essay, Saroyan recalled:The first painting of Hiler’s I ever saw is called The 14th of July. Six or seven or eight years ago the painting was out at The Legion of Honor Palace, if that’s the name of the place. I didn’t know Hiler at the time, but I knew that picture and I was glad he’d painted it. It’s a picture of a moment of reality in the world, among the living, at Marseilles. To this day I’ve never been to Marseilles. If I never reach Marseilles before I die, I’ll still remember the clarity of that moment of reality in the world among the living (William Saroyan, “A Note on Hilaire Hiler,” in Hilaire Hiler et al., Why Abstract? [New York: J. Laughlin, 1945], p. 34)APG 8843 MW/ZDR HH8843

- Shipping Info

-

STORAGE AND SHIPPING INFORMATION

As the Buyer, you are responsible for the pick-up or shipment of the property you have purchased.

As a courtesy, the Seller has made arrangements with a variety of third party shippers to provide shipping quotes for Buyers. Please note that shipping remains the responsibility of the Buyer, and we highly recommend getting quotes during any preview period for large, fragile or heavy items so you can consider the shipping costs before bidding. As set forth more fully in the Terms of Sale, under no circumstances will the Seller or Bidsquare be held responsible for items entrusted to a third party shipper.

Shipping small items by common carrier (UPS, FedEx, DHL or USPS): Each of the Sellers has engaged shippers to pick up several times a week. Once the Seller receives your payment and the completed shipping form authorizing the release of your property to the shipper, the Seller will add your lot(s) to the list for the next pick up. Shipping quotes will be included in the invoice.

Shipping larger items by freight (for example: furniture, bulky or odd shaped items): For items that exceed allowable dimensions or weight restrictions of UPS, Fed Ex and similar carriers, the Seller may provide assistance in arranging for delivery by freight. Please keep in mind that delivery of these types of items can be an expensive proposition, so you should consider this before bidding. Please remember that it is your responsibility to pay for all deliveries.

Pick up: Please check the Seller’s pick up policies and be sure to bring your own packing materials.

Removal of Property:. Regardless of whether you arrange to have your property shipped or picked up, all property must be paid for and removed from the Seller within 14 days of the auction. Storage fees are charged beginning on day 15. For more details see below and see our Terms of Sale. Neither the Seller nor Bidsquare is responsible for any damage or loss of property purchased but not removed from the Seller within 14 days of the auction. Starting on day 15 following the acution, the Seller may, at its sole discretion, remove the purchased Property to public storage at the Buyer’s risk and expense. All associated charges will be added to the total or subsequent invoice and must be paid in full before the Property will be released.

Property purchased and left at the Seller for 90 days or longer will be sold or donated for you, at the Seller’s sole discretion.

Frequently Asked Questions

May I use one check to pay for the invoice and shipping charges?

Yes. You will receive a combined invoice for the item that includes shipping charges.Will I be charged tax for picking up the item at the Seller?

An 8.875% New York sales tax will be added to your invoice if you pick up your property from the Seller. This tax will be waived if you have a resale number. You must complete the proper documentation in order to avoid the sales tax charge.Do I need to pay for insurance coverage for the items in shipment?

We highly recommend insuring your items for their full value during shipping. If you choose to waive the insurance coverage, we require a signed waiver from you stating that you accept full liability for any damage that may occur in shipment.What happens if my item is damaged during shipment?

It is a rare occurrence, but if your item arrives damaged, you must keep all packaging materials. Notify the Seller immediately. Take photographs of the damage to the box as well as the item. A representative from the shipping company will make an appointment to come and inspect the damage and begin the claim process.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB